Women Handling Our Sacred Texts

I’ve photographed Jewish women around the world and in almost every conceivable setting and occupation. I find myself drawn to women who are exploring Judaism’s sacred texts from many different perspectives: as scholars and teachers, but also as the people actually creating the Torah scrolls themselves, and using them in new ways.

To my granddaughter, her bat mitzvah a few months ago was routine, not revolutionary. She led services and chanted her haftorah with ease, accompanied on the bima by a woman rabbi, cantor and gabai (lay expert), with her sister called up to read too. This is what she assumes girls and women always do.

In our time, Jewish women are scholars who study, teach, publicly read and write commentary on the Torah. But what’s routine ritual for my granddaughters in North America is, in fact not yet legal for women at the Western Wall in Jerusalem; I photographed some of them reading from the Torah as close as they could get to the Wall. Maybe this is what the Kabbalist Moshe Chaim Luzatto meant when he said in the 18th century, “Every act of God travels through byways.”I’ve photographed Jewish women around the world and in almost every conceivable setting and occupation. I find myself drawn to women who are exploring Judaism’s sacred texts from many different perspectives: as scholars and teachers, but also as the people actually creating the Torah scrolls themselves, and using them in new ways. To my granddaughter, her bat mitzvah a few months ago was routine, not revolutionary. She led services and chanted her haftorah with ease, accompanied on the bima by a woman rabbi, cantor and gabai (lay expert), with her sister called up to read too. This is what she assumes girls and women always do. In our time, Jewish women are scholars who study, teach, publicly read and write commentary on the Torah. But what’s routine ritual for my granddaughters in North America is, in fact not yet legal for women at the Western Wall in Jerusalem; I photographed some of them reading from the Torah as close as they could get to the Wall. Maybe this is what the Kabbalist Moshe Chaim Luzatto meant when he said in the 18th century, “Every act of God travels through byways.”

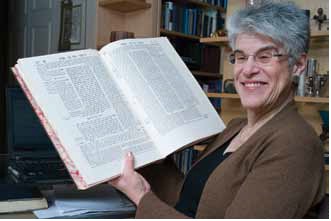

Rabbi Judhth Hauptman, The First Woman Ph.d. In Talmud

In The Essential Talmud, Adin Steinsalz wrote that “Time is an everflowing stream in which the present always obliterates the past.” Hauptman, Professor of Talmud and Rabbinic Culture at the Jewish Theological Seminary and author of Rereading the Rabbis: A Woman’s Voice (1998), which traces the development of women’s legal status in Jewish law, agrees. “Yes, there is an incredible change in the world. People used to think that women couldn’t absorb the material in the Talmud, that women didn’t have the intellectual capabilities. But nobody would say that today. There may be groups of Jews who won’t, in principle, teach women Talmud, but that’s because they will cite precedent, not say women don’t have the intellectual capacity. We have lived through this feminist revolution and come out the other side. We are not victims of the revolution; on the contrary, we are victors.”

Jen Taylor Friedman — The First Woman To Write A Torah Scroll

Now 30, she’s writing her third scroll; she’s also the woman who created the muchdiscussed doll “Tefillin Barbie.” Growing up in Southampton, England, she always beat the boys on math exams. At Oxford she discovered she was as good at Talmudic reasoning and halakha as at math. Add in her talent for calligraphy. “I’m happy using the skills God gave me. I didn’t decide I wanted to do this for some grandiose political reason; this career path opened up in front of me, and I followed it.” In the 21st century, Jen could be a scribe just because she wanted to. Here, she publicly declares the completion of the scroll she wrote for Congregation Shir Tikvah of Troy, Michigan

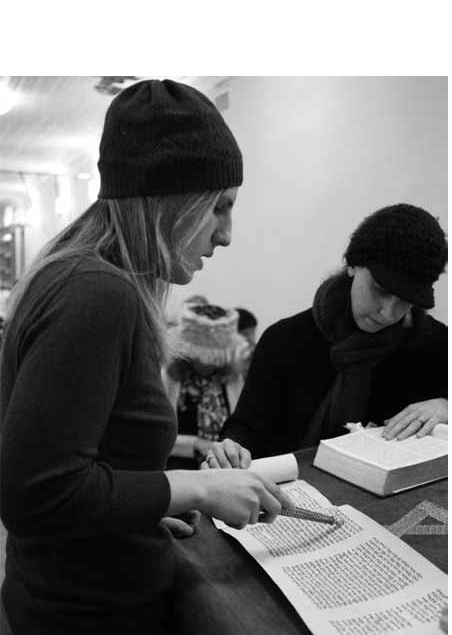

Rebecca Honig Friedman Reads The Megillah, Purim 2010

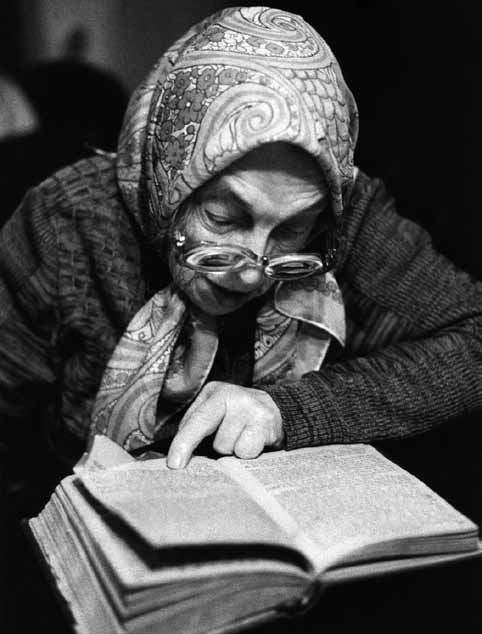

A Scholar In Her Time

Dvoyra (whose last name I never knew) was brought up in a distinguished family of rabbis, all of whom were massacred at Babi Yar. I met her in 1987 at the Podil synagogue in Kiev. Dyvora invited me home with her. Though she spoke no English, and I didn’t speak Russian, she indicated that she had a secret she wanted to share.

Her father’s and brother’s books had been confiscated during the Holocaust; she had hidden their Chumash (Five Books of Moses), wrapped in layers of fabric and plastic, atop her cupboard. The package hadn’t been opened since she’d placed it there in the 1940s. She climbed on a chair to fetch the dusty relic, then unwrapped and opened it to her favorite page before sitting down to read, as if she had just handled the book yesterday. She wanted me to know her as the learned women she had insisted upon becoming, and who still trembled with the joy this knowledge brought her.

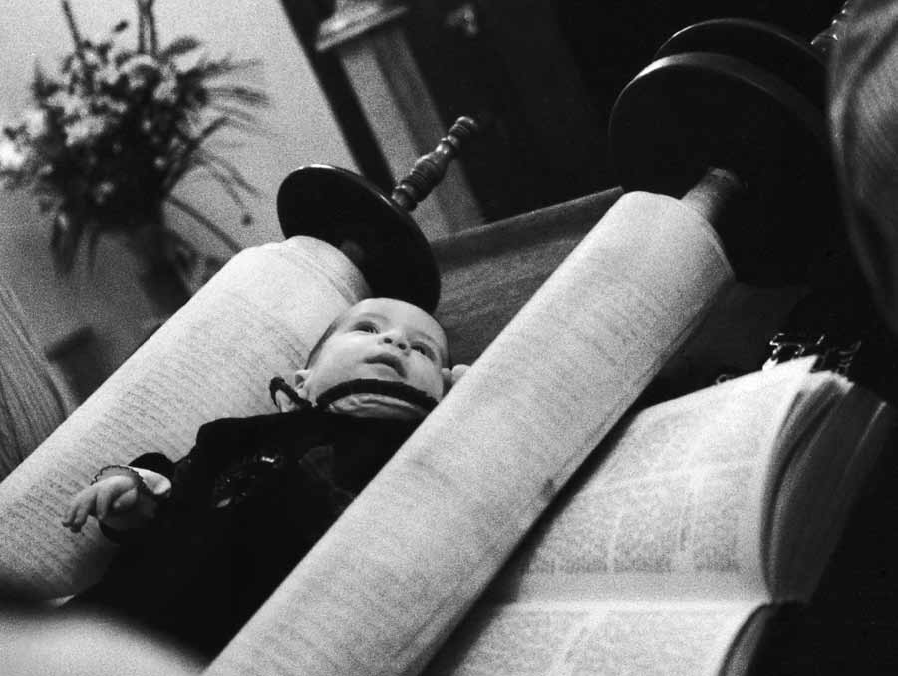

Simchat Bat: Welcoming A New Daughter Into The Covenant

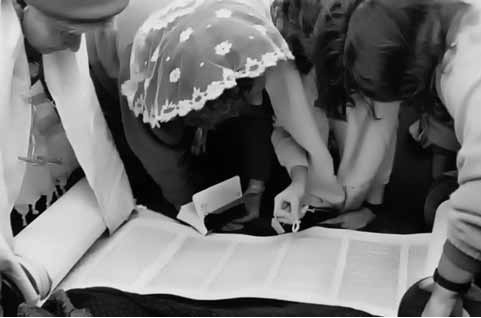

Reading Torah In Jerusalem

Like the photo on page 24, this one was taken in 1989, when the women of the International Committee of Women of the Wall gathered at the Archeological Garden, in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City.

Struggling With The Texts

Helène Aylon turns problematic passages into art installations. In “The Liberation of G-d, 1990–1996,” she covered Bible passages with a transparent overlay, marking the misogynist lines with pink highlighter. She’s a traditional woman with radical views, and her art startles with its frankness. In a recent installation at New York’s Jewish Museum, she exhibited a petition challenging the edicts of Karo and Maimonides that “women and minors and idiots and slaves” could not judge nor give testimony. And in the Jewish Museum of Australia, “I Look into the Passages,” highlights these texts with magnifiers. In a multicultural show now at Towson University, her “Self Portraits” show photographs with texts projected onto her face. Aylon says that “The Women’s Section,” shown in 1997, asked, “What would my pious Babas have said about my Torah highlighting? Would they have said, Hindele, Miturnisht (Helène, you mustn’t) or would they have clasped their hands, Geloipt su Guht, shoin tzeit (Thanks be to G-d, it’s about time.)”

The First Woman From The Netherlands To Be A Rabbi

Ordained in 1997 at the Academy for Jewish Religion, Chava Koster is the New York City Village Temple’s rabbi. Here she is blowing the shofar at morning prayers on her front porch. Chava learned she was Jewish at age 7. After joining a Zionist youth group as a teen, by 16 she knew she would be a rabbi. The response from her family, who had survived the Holocaust in hiding and afterwards played down their Judaism, was “Impossible!” This was Amsterdam in the 1970s, and there had never been a woman rabbi in the Netherlands. “Watch me!” she told them.

Making Torah Parchment From Deerskin

Rabbi Linda Motzkin, co-rabbi with her husband, Jonathan Rubenstein, at Temple Sinai in Saratoga Springs, New York, processes deer hides into parchment panels which will be used for Torah scrolls. The hides are given to her by local hunters, two of whom are Jewish. Pictured (left) in 2008, she prepares a deerskin hide in her backyard, having already recited a blessing over it, removed the flesh and soaked the hide in a limewater solution to loosen the hair. Once the hair is removed, the cleaned hides are again soaked, stretched and dried on wooden frames (below), then sanded several times and trimmed to proportion. The technique is first to thin the hides, then get them whiter, smoother and more receptive to the scribal art of writing Hebrew letters with a turkey feather dipped in fresh black ink. Motzkin’s project has turned into a communal effort; over 500 volunteers have assisted her so far. Although the process began in June 2007, at the rate Motzkin is going, she says she won’t finish for 12 years.