When Women Paint the Truth

What if Francisco Goya or Petrus Christus were female? Tirtzah Bassel’s paintings brilliantly explore this question, painter by canonical painter, and the sensation is akin to one’s ophthalmologist flipping refractor lenses. It’s hard to relate to Christus’s “male gaze” Nativity, for example, but, oh, with Bassel’s lens adjustment—Joseph making skin-to-skin contact with the newborn, a vaulted arch showing nine months of fetal growth, two Sheela na gigs spreading their vulvas to instruct birthing mothers—the female museum-goer’s vision is abruptly 20/20 for the very first time.

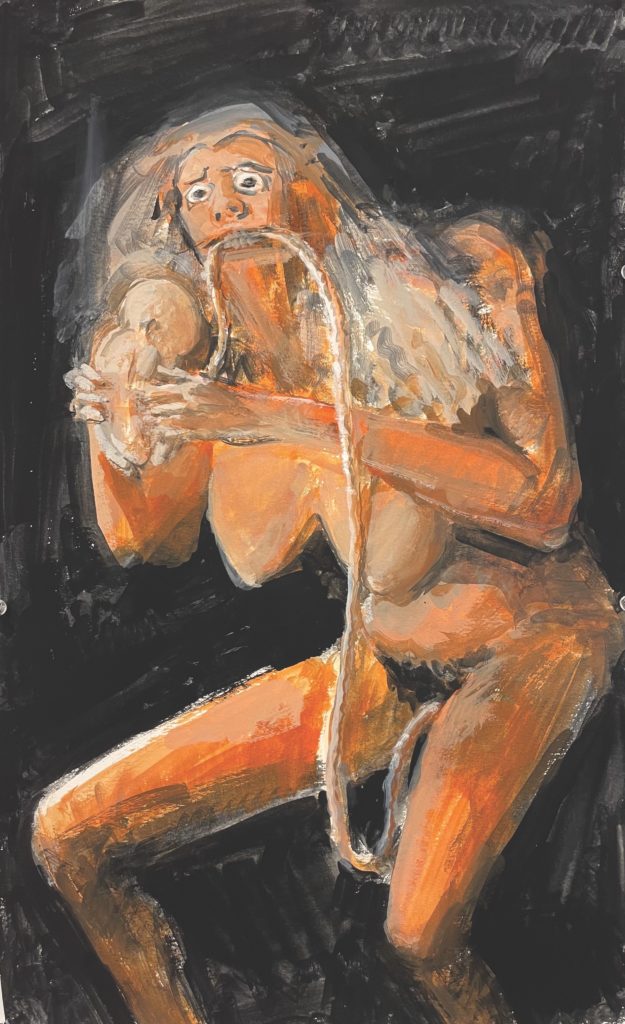

Tirtzah Bassel is an Israel-raised, Brooklyn-inhabiting artist who brilliantly, and belatedly (by 2500+ years), “reimagines art without the patriarchy.” Here she gives us a feminist take on Goya’s brutal painting “Saturn Devouring His Sons.” Goya’s work thrusts the viewer into the terrifying psychopathy of a father eating his child.

In the Roman myth, Saturn eats each of his children as soon as they’re born; it’s been prophesized that one of them will dethrone him. (He also castrates his father, throwing his testicles into the sea, thereby separating Heaven (Uranus) from Earth (Gaea)—that is, the male God from the female Goddess. Guess who wins?) Interestingly, Saturn’s wife saves the youngest child, Jupiter, by substituting a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes. This stone becomes the famous Omphalos Stone of Delphi. The bellybutton stone!

That was exciting. But to get back to Tirtzah Bassel …. her painting mimics Goya’s style, but instead of a cannibal father, she disrupts Western art history’s patriarchal canon by depicting something that’s been missing: What a birthing mother’s true feelings might be: frenzied, dark, polyvalent.

Here Bassel talks to me about her work:

The Nativity (after Petrus Christus), 36″x42″, gouache on paper, 2021.

What’s important to me are the basic questions: What is a woman? What is a mother? What is a rite-of-passage? My assumption is that images from the canon filter into our consciousness even if we’re inattentive. These images are not neutral. They embody ideas about gender, race, and class, and they answer our questions before we even know what our questions are: What is caretaking? What is the afterlife? What is a father? What narrative matters?

Take the birth of Jesus in a manger. We see chosen moments. Never the baby coming out of Mary. Never Joseph making skin-to-skin contact with the newborn. Never Mary’s experience centered.

In my painting after Petrus Christus’ “The Nativity,” I show the virgin conception as Mary pleasuring herself, and an arch depicting Mary’s womb in each month of gestation, with the final scene being Mary holding an extremely long umbilical cord with Jesus in her arms on one side and the cord still inside her on the other. In my reworking of another painting, Michelangelo’s “The Creation of Adam,” God is female and Adam is intersex. I call this painting “I Was Born This Way.”

Mother Severing the Umbilical Cord (after Francisco Goya), 13″x21″, gouache on paper, 2021.

In the painting we see the mother’s first act upon releasing the baby into the world. There is violence we’re not used to seeing: the powerful moment of a mother and baby needing to disconnect from each other. The moment of severing is a life-giving moment. And there’s a fierce side of motherhood that’s absent from our cultural imagery. There’s intensity here, but is it rage? Fear? Empowerment? Loss? You feel your mortality in this moment of birth, how close birth is to death.

When you have a baby, nothing prepares you for it. You’re alone with this. You can’t fake your way out, can’t intellectualize or compartmentalize this physical experience. When we only have the patriarchy’s images, we erase vital information for women: like how to inhabit our bodies—at particular moments and in life.

I came of age in the ‘90s. I thought feminism had already happened! But then I had the astonishing realization that there were so many women artists I was not aware of. And that we have to revisit the whole entire story, creating and uncovering, moving forward and backward at the same time.