When the Goddess Calls

Debbie Goldberg, 50, a graduate of Harvard Medical School, a respected internist, and a member of the Conservative congregation Tifereth Israel in Washington, D.C., sports a bumper sticker on her car that reads, “Witches heal.”

“For me, the tradition of witches is one of powerful, imaginative women whose healing abilities extend beyond the boundaries of rational, cognitive medicine,” she explains, “Witches use herbs knowledgeably, and create special atmospheres and rituals that allow people to imagine change in their lives, that support people positively, and that direct people’s energy into healing themselves.”

While Goldberg does not belong to a coven, she seeks to better understand witchcraft. Describing her current religious life, she says, “I’m largely a non-observant Jew looking for a niche.”

For Jews to whom the terms “pagan” and “witch” seem antithetical to Judaism—even abhorrent, given the numerous biblical warnings against polytheism and witchcraft—Jewish witches and Pagans may appear bizarre, cultic, kooky. Yet more and more Jews, nourished by the feminist movement, are not only donning the dual labels, but finding similarities between the two traditions.

Ruth Barrett, 40, a professional singer and fretted dulcimer player, sings in the High Holiday choir at Congregation Kehillath Israel in Pacific Palisades, California, where her father, Milton Bienenstock, is cantor emeritus. The Bienenstocks are among the founding families of the Reconstructionist movement. Barrett is also a Wiccan priestess of the Circle of Aradia, a legally incorporated religious “congregation” that is for women only. Barrett teaches magic, spell-craft and conflict- resolution workshops at colleges, women’s music festivals, and spirituality conferences. “I teach psychic development,” she says ways to work with energy, through ecstatic dancing, chanting, and visualization, with the purpose of bringing about desired goals. These goals might be looking for a new job, ending patriarchy, or just having a situation go the way you want it to go, while always honoring free will and the greater good of all.”

Barrett and her music partner, Cyntia Smith, have brought out six albums of Earth-based spirituality, music, original Goddess songs, and instrumentals, and they give concerts at feminist spiritual gatherings including the International Goddess Festival held in May in Santa Cruz. Their newest album, The Heart Is The Only Nation is available through Ladyslipper, 800- 631-6044.

Barrett’s daughter, Amanda, became bat mitzvah two years ago; at 15 she still attends Hebrew School. Margot AdIer, currently a reporter for National Public Radio, was 12 when she first immersed herself in Greek mythology and felt as if she had returned to her “true homeland.” Raised in a non-religious Jewish home, the granddaughter of renowned psychiatrist Alfred AdIer, her childhood heroes were Artemis and Athena. Not until adulthood did she fulfill her childhood wish of becoming a witch and a Goddess-worshipper.

AdIer, Barrett and Goldberg mirror the spectrum of Jewish women who find spiritual appeal in the various (not always well-differentiated) forms of Paganism—neo-Paganism, witchcraft (called Wicca), and Goddess spirituality. Though there are no statistics on how many Jews have embraced Paganism, anecdotal evidence indicates that its holistic, feminist, earthy, empowering, personal, creative, alternative beliefs and practices resonate deeply for thousands of Jewish women and men, both those who have been drawn out of Jewish religious practice as well as those who continue to practice Judaism in more conventional ways. At any given Earth-spirituality gathering on the East or West Coast, Jewish faces and names are strongly in evidence.

Many well-known Pagan writers and leaders are brainy, sensitive, funny, impressive Jewish women— AdIer, Starhawk, Deena Metzger and Marion Weinstein, to name just a few. Some Jewish women who have turned to Paganism seem to be frustrated rabbis, born too soon, who saw no option for a feminine-centered cosmology within the Judaism of their generation. Because Paganism celebrates individuality, urging its members to create their own rituals and theology, it is difficult to provide formal definitions of the religion. There are some basics, however: Mind can mold matter; all events are generally meaningful, and chance does not really exist.

In her comprehensive overview of Paganism, Drawing Down the Moon (Viking, 1979), AdIer defines a Pagan as a member of a polytheistic, tribal, nature religion. The Latin term Pagan, which simply means “of the country,” stems from the history of Christianity, whose first converts were city dwellers. “People in the countryside never got the news,” Adler says. A witch, she explains, is an initiate of the religion called Wicca, a pre-Christian nature religion that worships Goddesses (one or many), and sometimes Gods.

“We have what we call a ‘Web of Life’ consciousness,” explains Ruth Barrett, “an understanding that everything in life is connected to everything else. This is feminism’s strength, too. Everything we do or don’t do has an effect, a kind of spiritual amplification of the ’60s idea that if you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem.

“Witches believe that everyone has a psychic vote, and we learn how to use that vote through rituals, through utilizing and directing power. Being a witch means being active in the world. It means being as conscious as possible, in our personal interactions, our politics, everything. We can’t end the problems of child abuse or rape, for example, because these institutions are co-created by society as a whole, but we can add our energies towards changing these problems.”

Paganism’s feminist and environmental emphasis appeals both to people alienated from the patriarchal religions in which they were raised and to those who feel a critical need to reconnect with the earth.

The Pagan worldview, Adler writes, does not separate the animate and the inanimate, or divide the divine, the human, and nature. “The subversive core of Paganism is that we are the Gods,” Adler explains. “We have the Goddess within us. That’s very powerful, especially for women who have felt they are nothing and their bodies are nothing. The ground of the sacred is here and now. You don’t have to die to get to the good stuff.”

Adler admits that her interpretation of the immanence of the Goddess is metaphorical and therapeutic. Others have a more literal understanding of the concept.

“I feel that the divine is present in the tree, and in the star, and in the wolf, as present there as in the human,” says writer Deena Metzger, well-known as the nude woman on the post-mastectomy poster who poses sporting a tattoo of a tree on her chest. “And if you can imagine that the divine lives in the tree, you can imagine it lives in women. Because of this perception of an inspirited world, I have been met by Pagan thought.

“That’s a place where Judaism doesn’t feed me,” she adds. “Recent attempts to bring nature back into Judaism feel liberal to me, but not profound, because I don’t know anyone yet in Judaism who says the tree, the person, the animal and the bird are simply variations of each other and of the divine.”

“For me,” adds Adler, “Paganism is a way to get the juice and mystery of ecstatic religious tradition, without taking on dogma, just because you dance and sing for five hours straight doesn’t mean that you lose your integrity as a rational being. Why can’t one dance and chant and drum in total ecstasy, and then wake up the next morning and be a computer programmer? You can live in different realities at the same time.”

Take, for example, a ritual Starhawk describes in The Spiral Dance, the best-selling introduction to witchcraft first published by Harper-Collins in 1979 and revised ten years later:

“The moon is full. We meet on a hilltop that looks out over the bay . . . . The night is enchanted. Our candles have been blown out |by the wind] and our makeshift altar cannot stand up under the force of the [gale] as it sings through the branches of tall eucalyptus. We hold up our arms and let the wind hurl against our faces. We are exhilarated, hair and eyes streaming. The tools are unimportant; we have all we need to make magic: our bodies, our breath, our voices, each other….”One by one, we will step into the center of the circle. We will hear our names chanted… and remember: ‘I am Goddess. You are God, Goddess. All that lives, breathes, loves, sings in the un-ending harmony of being is divine.'”

While rituals can be dramatic outdoor events full of drumming, dancing and chanting, they don’t have to be. The Circle of Aradia rents community centers or churches for its seasonal gatherings, since its outdoor rituals drew too much unwelcome interruption. Covens often meet in homes. Wherever rituals take place, however, they include several steps: a purification of space by casting a circle; purification of self, such as being anointed with a mixture of salt and water; honoring the four directions— earth, water, fire and air, and the spirit that holds them together; a welcoming of Goddess and/or God; and eating, drinking and socializing. The goal is a religious experience that alters one’s consciousness.

Despite Paganism’s belief in individuality, it is not without rules. Wicca, especially, has more formal boundaries than other forms of Paganism. The Wiccan code of ethics states, “You shall harm none and manipulate no others against their will.” But as Paganism comes of age, it has not yet confronted the implications of its theological positions. It has not taken a stand on issues such as abortion, nor has it organized soup kitchens and halfway houses, according to Adler (who now, by the way, worships alone because of her busy professional schedule).

Wiccans are organized by covens, autonomous havurah-like groups traditionally limited to thirteen people who do spiritual work together. Thirteen, the number of lunations in a year, is a sacred number for witches. Often participants take turns being priests or priestesses, which simply means leading the ritual.

One of the best ways to understand what attracts many Jews to Paganism is to listen to their stories of searching and epiphany, most that began in childhood and adolescence. Penny Novack was raised in the Midwest as a Southern Baptist, began her spiritual quest at the age of 12, converted to Judaism at 35, still keeps kosher, belongs to a synagogue in Massachusetts, is a member of a Rosh Hodesh group, and is a Pagan.

In 1968, she says, at the age of 27, she had “an argument with God,” in which she felt at a dead-end with a God whose image was male. In order to grow religiously, she felt she needed, “a God imaged as female as strongly as a God imaged as male.”

Today, she characterizes her open-house community celebrations as “disorganized, gregarious fellowships” that she shares with her Jewish husband, Michael, her children, who have been raised Pagan, and a circle of friends that can number from fifteen to fifty.

Despite Jewish feminist reinterpretations of God as Goddess, “for most Jews, ‘Goddess’ is a political statement rather than one that comes from the joy of perceiving deity,” Novack says. Len Rosenberg, on the other hand, often drew pictures, as a boy, of a male God standing beside “His wife, whom I called Mother Nature.” Later, when he attended folkshule, he found the image of the Sabbath Bride enchanting. Today he practices Hinduism and Paganism, but still considers himself ethnically Jewish.

“If I pass a mezuzah on a door, I reflexively reach up to kiss it,” he says. “Those are my roots. I can’t cut them off.”

As a child, Marion Weinstein dressed her dolls up as witches, watched TV ministers, requested lessons in kabbalah, and studied religion on her own. “I started questioning the whole structure of deity at age 13,” recalls Weinstein, a witch who for fourteen years hosted a radio show on WBAI in New York, called Marion’s Cauldron, in which she interviewed occult experts, taught occult techniques, conducted group rituals and discussed topic such as psychic phenomena, dream research and witchcraft.

“If you’re going to identify with a deity that doesn’t look like you in any way, then you’re not going to feel personally connected,” Weinstein says. “But if the deity looks like you

Pagans celebrate Eight Sabbats, or holidays: Winter Solstice (Dec. 20-23); Candlemas (Feb. 2), harbinger of spring; Spring Equinox (March 20-23); Beltane (May I), honoring the flowering and fertility of the Goddess; Summer Solstice (lune 20-23); Lammas (August 3), the first harvest; Autumnal Equinox (Sept. 20-23), and Halloween, or Samhain (Oct. 31). and sounds like you and reminds you of your mother and grandmother, then all the beauty and magic of the ‘Creatrix’ will be yours automatically. You are a microcosm of deity.”

Born Miriam Simos, Wiccan leader and author Starhawk absorbed Judaism from her religious grandparents, and continued her Jewish education through Hebrew high school and Camp Ramah. “As I reached young womanhood, I sensed that the tradition as it stood then was somehow lacking in models for me as a woman,” she writes in The Spiral Dance. At 17, she hitchhiked up and down the California coast, began feeling connected with nature in a new way, but didn’t know how to “name” her feelings yet.

She adopted the name Starhawk after she dreamed of a hawk flying across the sky in a universe that shimmered and split to reveal an underlying shining pattern. “The hawk swooped down and turned into an old woman. I felt I was under her protection,” Starhawk recalls.

These stories mirror the needs many Jewish Pagans feel are, or were, unanswered in Judaism. To fill those needs. Pagans are eclectic, absorbing everything from Greek religion and Native American thought to Buddhism. And, though frequently raised in secular Jewish homes, many Pagans hang on to Judaism, finding a deep-rooted sense of Jewishness impossible to dismiss. New Moon New York, a Pagan networking organization, does not schedule events on Jewish holidays because many of its participants observe them, says the group’s program coordinator. Nan Alexander.

In fact, Jewish Pagans say there is much the two traditions share: Both are ancient, tribal religions; both stress ethics and a connection to the land, both celebrate lunar cycles and seasonal holidays, both emphasize community: neither proselytizes.

The number of Jews in Paganism reflects Judaism’s lack of dogma as well as the American emphasis on individualism that encourages choice instead of obligation in religion, says Rabbi Lane Littman of Congregation Kol Simcha in Laguna Beach, California, “it also speaks to the abysmal Jewish education that took place a generation ago. If Jews had been educated better, there wouldn’t be so many Jews who are Buddhists, Wiccans, unattached or hostile to Judaism. Today, many Jewish institutions are working towards this issue.”

Littman points out that the concept of harmony with the earth is organic to Judaism. “Our entire holiday cycle has to do with the harvest and lunar phenomena,” she says. “Sukkot is the full moon after the equinox. Passover is the full moon after the equinox. Tu B’Shvat is when the trees bud.”

Deena Metzger, who celebrates holidays such as Passover and Hanukkah, says Judaism gave her an ethical, moral and political consciousness, but did not “take” her “to spirit.” It took her, instead, to law. She describes herself as very observant, but not in the prescribed ways or time-bound moments. When she lights candles, she says, she always remembers the Sabbath candles and what they mean. Yet she does not always light candles on Friday night at sundown. “I practice the idea of the Sabbath all the time,” she says. “It might be tonight. It might be tomorrow night. It might be an hour in a day. The Sabbath is the most profound offering of Judaism.” Does Metzger say the traditional Jewish candle lighting blessing? “Only if I light candles on a Friday night,” she explains.

When Ruth Barrett’s daughter Amanda became bat mitzvah last year, Ruthread the Torah blessings, but altered them: “Brucha at Shekhina, Malkat ha-olam . . .”[Blessed are You, Shekhina Queen of the Universe]. Her daughter recited the traditional words: “Baruch ata Adonay, eloheinu melech ha-olam . . .” (Blessed are You, King of the Universe].

For Judy Harrow, a 48-year-old Manhattan civil servant and coven leader, Jewish identity is a complex, painful issue. Raised in a nonobservant home in the Bronx, on the same block as her religious, Yiddish-speaking grandparents and surrounded by Holocaust survivors, Harrow says that when she first found a religious community that expressed her values better—Paganism—she tried to close the door on being Jewish. Disturbed by the example of Jews for Jesus, who tried to “have it both ways” by remaining simultaneously Jewish and Christian, she felt that if she couldn’t practice Judaism normatively, she didn’t have the right to call herself Jewish.

Over the last five years, however, Harrow explains that, “I can’t turn my Jewish side off,” though she allows that her polytheistic vision arguably excludes her from being normatively Jewish.

“When you cannot adhere to the Shema— that Adonai is One—that’s really it,” she says. “I was at a Friday night dinner at a friend’s house where everyone sat around debating whether or not I’m Jewish. It all depends on what you mean by ‘Jewish.’ Am I a monotheist? Absolutely not. Am I ethnically Jewish, do I support the Zionist cause? Absolutely yes,” Harrow’s personal experience convinced her of witchcraft’s healing powers. In 1979, she was diagnosed with cancer. A group of friends cast a circle, and chanted until they had created a high level of emotional intensity, focusing it all on her. The malignancy disappeared and has not recurred. “Visualization and other techniques can influence the immune system,” she says. “So much of disease has a stress-related component. Why not work with the mind and release that component to make space for healing?”

She is passionate, too, about Earth spirituality. “Look at Mother Nature,” she says. “She may not be the center of your life, but She is in need; she is in pain; she is in danger. Whether or not you worship Her, you live off Her, and your life is dependent on Her life.

“The monotheistic model,” Harrow adds, “gets humanity in trouble. Any one face of God is inherently oppressive. If God is male, women are left out. If God is female, men are left out. If God is old, children are left out. If God is Athena, Aphrodite is left out. From one God to one way is a step people make easily,” For Starhawk, the recent death of her mother helped her to focus some conflicted feelings about Judaism. At services in the synagogue, Starhawk says, “Over and over I found myself emotionally comforted by the music, the atmosphere, the people—as long as I ignored what the words actually meant. But I understand the Hebrew, so I found myself split.

“I said the Shema with my mother on her deathbed, and there was that powerful connection with all our ancestors. Yet that prayer just doesn’t work for me.”

Not all Pagans are polytheistic. “When people ask, ‘Is Goddess religion polytheistic or monotheistic?’ I just answer, ‘Yes,'” laughs Ruth Barrett. “So for me, there’s no conflict between Paganism and Judaism. The Goddesses in their various guises are parts of a whole. There’s a completeness that IS the Goddess, and there are also different Goddesses that embody different aspects of Her. It’s similar to Nature: there is rain, fire, wind, water—yet the larger context is Nature, and within Her are individual archetypal energies. “If I weren’t attached to female metaphors my concept of Goddess would fit really well into Reconstructionism, which views God as the force in the universe that creates and that is inherent in everything.”” There is enormous flexibility in Judaism as to how to interpret the belief in one God,” Rabbi lane Littman notes. “We call God ‘El Shaddai,’ ‘El Elyon,’ Elohim,”Adonai,’ ‘Shekhina.’ Does that mean we have five different Gods? No. Those are all aspects of the divinity. What we don’t use is Hecate, because she is not part of our cultural inheritance,”

Tikva Frymer-Kensky, professor at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, scholar of Near Eastern religions and author of In the Wake of the Goddesses (Free Press, 1992), adds that Judaism speaks about God in non-gendered metaphors such as ‘Rock’ or ‘Living Waters.’ But because of social patriarchy, she explains, Judaism chose to emphasize the power metaphors which are male—Master, Father, King.

Some Pagans have tried to formally integrate Judaism and Paganism. Penny Novack founded the Jewish Pagan Network, an attempt to help Jewish Pagans look at the religion of their birth in the light of Paganism. After three years, two Sabbath study gatherings (which drew about ten people), and many calls and letters, Novack gave up. “They didn’t want the two parts of their lives brought together,” she concludes.

Novack is wistful about her search to meld her two religious impulses, expressing a desire to increase her Jewish observance. “I try not to be schizophrenic about being both Jewish and Pagan, but I find myself alone a great deal of the time,” she says.

Her sensitive vision of Judaism, rooted in the sacredness of nature, leads her to compare Torah to beautiful natural sites, like Shelburne Falls (near her home in Massachusetts), a volcanic dome with awe-inspiring formations: “That place has a feeling of time, history, beauty. I experience Judaism as being like that dome,” When Novack lights Sabbath candles, she visualizes women everywhere lighting at the same time, starting a wave of light that goes all the way around the world.

Novack’s efforts spurred Steve Posch, a 37- year-old writer, actor and storyteller, to co-found a Pagan congregation in Minneapolis called Beit Asherah, or The Golden Calf Synagogue. “It’s in your face,” Posch comments about the name, “but it’s intended to be playful, like, ‘there, we’ve broken the final taboo.'”

Sabbath and holiday celebrations attract between ten and 25 people to parks, “temples” in private homes, or wherever the congregation chooses. “We get together and speak the same language,” Posch says.

At their “Return of the Goddess Seder,” traditional Jewish songs and neo-Pagan chants blend. “We eat the bitter herbs and remember the coming of patriarchy,” Posch says. “We improvise the Cursing of the Patriarchy instead of reciting the Ten Plagues.”

Men and patriarchy are not synonymous, says Posch, adding that as a gay man he feels more comfortable in a matriarchal culture with Goddess imagery.

He admits that his group probably seems “scary and threatening” to mainstream Jews. “We’re redefining Jewishness for ourselves in a way that seems to have been excluded as a possibility by tradition. We are flying in the face of centuries of self-definition, you know how uncomfortable people get when you change their definitions.”

Goddess spirituality may not affect a majority of mainstream Jewish women, but it is definitely creeping into non-traditional Jewish circles which are committed to breaking ground in feminist liturgy, Janet Camay is a member of Shabbat Shenit, a group of women (including rabbis and cantors) in the Los Angeles area who meet once a month, taking turns at crafting services which, though rooted in traditional forms such as the Amidah, are experimental and innovative. “We cast a circle to create sacred space,” Camay says. “We invoke Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah. Each time we say the Shema, it’s different.” She offers an example: “Listen, Sisters, We’re All Part of Godd/ss, and We All are One.” According to Lane Littman, a member of the group, the spelling Godd/ss is designed to promote the ineffability of God’s name and to distinguish it from masculine or feminine names for God. Different members pronounce it differently.

Littman stresses that the Jewish mystics of the medieval town of Tzfat—not Pagans—were the first to cast circles. “They’d dress in white, go to each direction in the city, and call in the sacred spirit of that direction. They would end with the Sabbath Bride in the east.”

“Our group is not about the Goddess,” Carnay adds. “It’s about finding spirituality that resonates in our lives today.”

An artist, Carnay created a sculpture in the form of an amulet entitled “Woman at the Wall,” a sort of Goddess boldly blended with an allusion to the feminist Jewish group which searches for equal representation during prayers at Jerusalem’s Western Wall. Carnay explains: “It’s a woman of courage, a metaphor for women who take risks in moving away from traditions to create a sacred space.”

Goddess religion has also encouraged Jewish women to investigate their spirituality—and then return to Judaism, Littman suggests. And while Tikva Frymer-Kensky, the rabbinical school professor, doesn’t expect Jewish Pagans to come flocking back to Judaism, “There is something emotionally satisfying for Jewish Pagan women in seeing Judaism become more feminist,” she says. “When they hear real feminist Jewish services and real feminist Jewish understandings of Bible, formerly-Jewish witches have tears in their eyes.”

“The choices open to me 25 years ago were few,” Ruth Barrett says. “I took my spirituality and ran. I may go on to become a rabbi—and I’m not saying that to be flippant. Who knows? Life is long.”

Rahel Musleah is a journalist in NY who contributes regularly to The New York Times, Publishers Weekly and other publications.

The Great Goddess In Elsie Goldstein

by Susan Schnur

Marija Gimbutas’ radicalizing archeological-mythological work [The Language of the Goddess: Unearthing the Hidden Symbols of Western Civilization] plunges readers back 9000 years to various Goddess-worshipping, gynocentric, peace-loving cultures that lasted, Gimbutas argues, for over 4500 years. Reviewing thousands of archeological artifacts—particularly ubiquitous female statuettes from farming cultures in southeastern Europe from 6500 B.C.E. on —Gimbutas reconstructs early cultures that rested upon ” a life-affirming, profoundly organic world-view that locates the Goddess within each individual and within all things in nature,” as opposed to the male God who is largely conceptualized as transcendent; whose location is a distant heaven.

Over the last few years, a virtual Goddess cottage industry has sprung up around Gimbutas’, and other archeologists’, finds. Many small, lively businesses are crafting replicas of ancient female figurines—a pocket-sized pewter Goddess of Willendorf (c 30,000 B.C.E), a ceramic Cucuteni bird Goddess, or a Celtic Sheela Na Gig in bonded stone.

Cut for a moment to Elsie Goldstein, a 78-year-old, strongly identified Jewish secularist/political leftist and Gray Panther from Evanston, Illinois, who knows nothing about Marija Gimbutas, the Goddess-figure cottage industry, or the women’s Pagan revival. Nevertheless, for nine years, she has been moved to create clay female figurines of religious significance-holding Hanukkah candles, adorning seder plates, as Sabbath candlesticks.

Let’s listen to Elsie, and then ponder the continuum: the connection between Goldstein’s naif folk art, her “graven images” which resonate for many Jewish women, and theologian Carol Christ’s comment that, “Not until I said Goddess did I realize that I had never felt fully included as woman in masculine or neuterized imagery for divinity.”

Elsie: “Women buy these female figures, like my Hanukkah Womenorahs, and then they tell me their personal stories. An Orthodox woman told me she had been sexually abused by her father when she was a child, and she used to pray each night not to wake up the next day. When she did wake up each morning, it confirmed for her that there was no God. She used her Womenorah in therapy; she said it helped her know that it was all right to be a woman and a Jew.

“What got me started was all this Jewish art of Chassidic men. I saw a menorah of these male figures, and that got me mad. Everywhere I looked, there’s these damn males taking over. The male menorahs clinched it for me: enough already! “What I like about some of my female figures is that they are freestanding, you can move them around to relate to each other My women touch each other, they hug, they look. This is what women have to offer: we relate like Carol Gilligan says, we’re socialized to think of one another, to connect.

“Many years ago I read Robert Graves. It made sense to me that life and death revolved around Goddesses; people didn’t know about the male role in procreation. I always liked the primitive Goddesses— they’re emotional, less contained, less rational. These are compliments.

“My husband and I just returned from a trip to Greece, to the Temple of Isis, the island of Debs. So I’m in Macedonia sitting on a 3500-year-old marble bench—you feel you’re back in time—the fact that there was such a different time, it’s transporting. I’m posing for Sol to take a picture, and two or three young people go by, and they bow to me. We were all transported. “I saw the worship of the Goddess, and I translate it into the worship of a woman. Not that we should be worshipped especially, but it’s appropriate that women be among those who are worshipped.

“I charge $175 for a Womenorah, and I feel guilty about it; it’s a lot of money. But my women are very time-consuming, and people are meshugeneh, they pay, because, I guess, these figures seem to say something deep. Sometimes I have to throw away a figurine because there is no way to repair Hen What feelings that provokes for me! And so I throw it out quickly because I feel upset, squeamish.”

What happens to the consciousness of Jewish women when we begin to wonder whether our spiritual-mythological history begins not only with our Jewish ancestors, Sarah and Abraham (whose Hebrew followers were, after all, part of an Indo-European patriarchal, pastoral, mobile, war-oriented larger culture that worshipped male deities), but also with a culture (matrifocal, agricultural, sedentary, peaceful, egalitarian) that is perhaps five or six thousand years older than our Jewish one, wherein the Goddess Creatrix is posited to have been worshipped as the central divinity?

What happens to our consciousness when over three-quarters of Western history is newly potentially constructible as essentially feminine? When the hoary Hebrew calendar year 5754 seems suddenly to represent a fairly brief stint?

What happens to someone like Elsie Goldstein, committed secular Jewish septuagenarian, when she formally meets up with the feminist energy that’s been generated in Gimbutas like circles? When she holds in her Yiddishe hant her first reproduction Neolithic Cucuteni bird Goddess carrying the mature eggs of creation in her buttocks, and is enthralled?

When patriarchy seems no longer Western history’s absolute norm—but rather a lost weekend?

“Long long ago, in the time before remembering…”

by Susan Schnur

Every decade or so, a cultural classic comes along that establishes a new developmental benchmark for feminism. Free to Be You and Me was one. New England-based storyteller Jay Goldspinner’s work is among the new classics, that seem to be springing Athena-like from the profoundly transformative gynocentrism that defines the women’s spirituality movement.

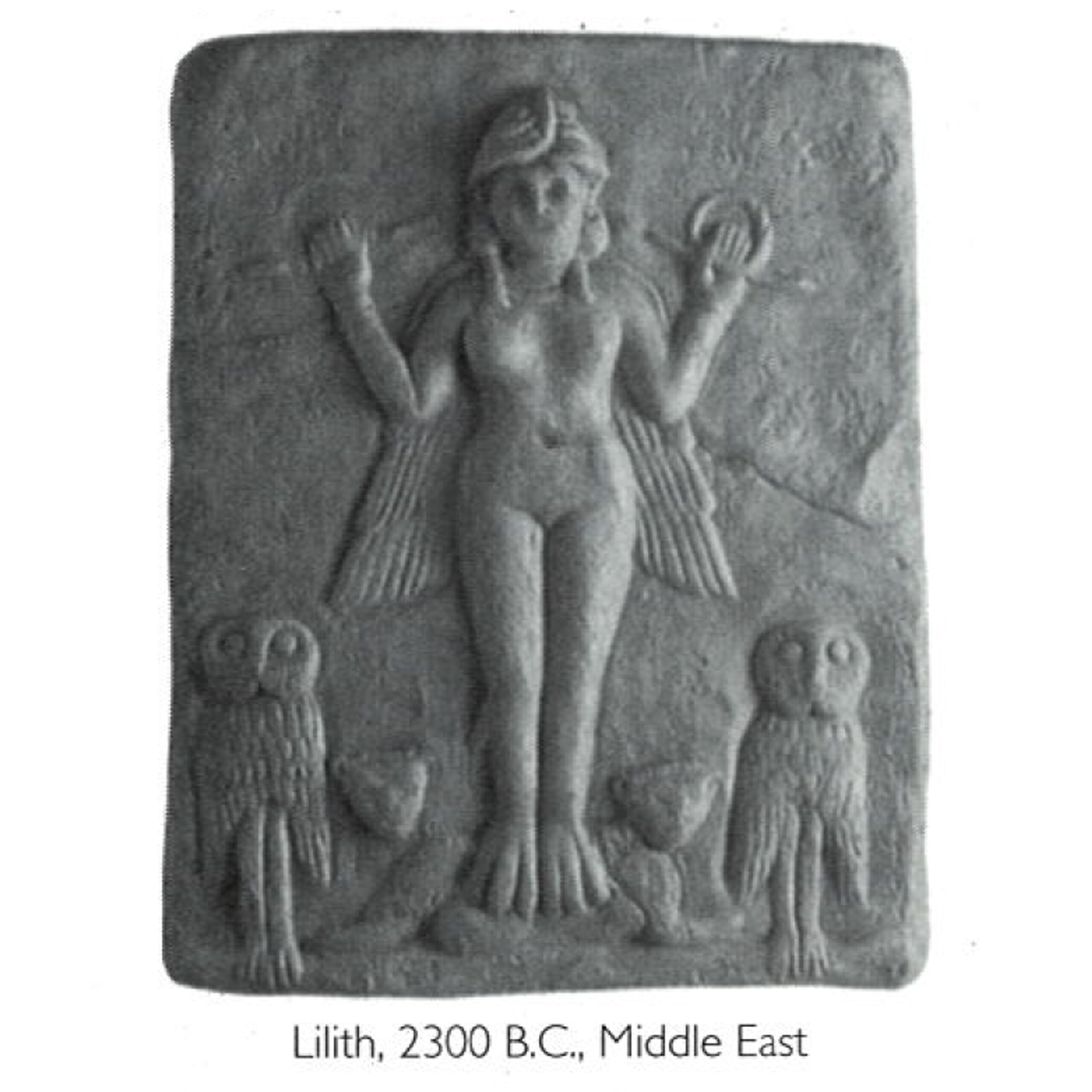

On her quiet, powerful audiotape [Rootwomen Stories, $ 12, available through Jay Goldspinner 56 Orchard St., Greenfield, MA 01301, 413-773- 8033], Goldspinner tells a broad, inclusive range of deeply-felt tales: from Lilith (who turns herself into “a most magnificent dragon”); to the Irish Peggy O’Donal (who thinks, like many women, that she has no stories to tell and no songs to sing); to Betsy Bell and Mary Gray, two 18th- century English sweethearts (one a healer the other a gardener/cook) who share a bed in a simple thatched cottage and die nursing others through a plague.

“I wasn’t always a woman-loving Wiccan,” says Goldspinner, who, at 62, describes herself as a Goddess-follower and witch. “Once I led a conventional—well, semi-conventional— life. When I gave that up, I lost a lot; marriage, family, children, regular job. There was a lot of pain to it.”

Goldspinner’s tales, stemming as they do from the storyteller’s deep internalization of a social script that was written by women instead of men, posit, indeed, a different understanding of what the world is about: It is holistic, nature-loving, embedded in a really ancient past (millennia before Eve). Lilith becomes, for example, not a feminist tale of re-visioning, but the warm and newly retrieved original—the long-awaited replacement for the Adam-and-Eve counterfeit with which we’ve lived for so long.

When Lilith is banished from Eden, she finds “that life in the desert was hard, but she could survive, and it was beautiful. When the flowers bloomed, it was fragrant. And she flew over the land, and she watched the moon, and she swam in the sea, and she bore children—the Seraphim, those women with wings and songs, they were her children; and the wise and mighty Sphinx who still sits in the desert, she was her daughter and the great tall cedars of Lebanon, they were also her children.”

Such aesthetic and moral perfect pitch as Goldspinner’s speaks to a coming-of-age of cultural feminism. The women’s spirituality movement, for example, does not feel that it is inventing itself (a process that requires brassy music), but rather that it is practicing the craft of retrieval—a procedure bolstered by an emotionally entitled sense of legacy. Generally, retrieval affords practitioners more self-assurance than does invention (and consequently often leads to better art). If Gaian feminists are not just “making things up,” as it were, but rather carefully brushing the sand off neglected artifacts (and stories) that have been there all along, it’s a process (less scary, more self-affirming) that brings one into a more compassionate relationship with the Muse.

So how did someone like Goldspinner enter the magical [sic] world of storytelling? “Obviously through my mastectomy in the 1960s,” she explains good-naturedly. “Some time after my operation, I read that Amazons were one-breasted in order to prove that they didn’t need men—that they were complete in themselves. And this was a profound, lifesaving reinterpretation for me. I then found myself wanting to read stories about Goddesses, but they were impossible to find. Stories about women are generally twisted and put us in a bad light. If we’re powerful in the stories, we’re also evil. So then I thought, ‘Well, if I want to hear these stones, I’ll have to tell them myself”.