We All Stand Here Ironing

Tillie Olsen and her daughters, 1947. Photos Courtesy of Julie Olsen Edwards.

Tillie Olsen wrote her important stories and essays in a tradition of Jewish radicalism that insists on the struggle for economic, gender and racial justice as a burden and privilege of Jews—rooted in a history of oppression and survival, in the conviction that such experience demands empathy and activism. Devoting her writing and personal life to these values, Tillie Olsen was also the great writer of the experience of motherhood. In the unique, poetic prose of the stories, she plumbs the deepest layers of an experience that can combine overwhelming love with exhausting, demanding labor, devotion with anger, power with helplessness.

Olsen, among the most influential writers in American literature, certainly in my writing life, a maternal presence in her literary work and in a friendship that lasted from 1975 until she died in 2007. I want to claim her now not for myself, though including myself, not for the entire world, though she rightfully belongs to the multitudes, but especially for the people who struggle against injustice everywhere.

For Olsen, the conditions of our inner lives are inexorably interwoven with the material conditions of our lives in society. As she once wrote: “… not only the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, but the establishment of the means—the social, economic, cultural educational means to give pulsing, enabling life to those rights.”

In her writing and in her support for other writers, she joined the struggle.

In the great novella Tell Me A Riddle, Eva—a woman considered old then at 69—is about to die. To her husband, who for most of the story, names her out of his own contempt: “Mrs. Orator Without Breath,” “Mrs. Enlightened,” who asks bitterly, “You think you are still an orator of the 1905 revolution?” she responds: “To smash all the ghettos that divide us—not to go back, not to go back—this is to teach.”

Confined to a hospital bed with untreatable cancer, Eva is told by her daughter that a “man of God” came to her bed to comfort her. “The hospital makes up the list for them,” the daughter says, “and you are on the Jewish list.” But Eva, weak, yet still driven by her defining passion, shouts, “At once, make them go and change. Tell them to write: Race, human; Religion, none.”

Still she believed, her husband says near the end of the novella and in the last moments of her life. She may no longer be able to hear him when he finally calls her Eva, her name, and asks: Still you believed?

O Yes is her story of racial friendship and separation, a white child, a black child, friends until they reach a certain age and then, “how they sort…a foreboding of comprehension,” thinks the mother. The story was written long before Toni Morrison named an “Africanist presence” as a formal turning point in much white American literature, describing encounters between white and black characters in which a black character, “lubricates the turn of the plot and becomes the agency of moral choice.” Olsen may have sensed the nature of such moments when the young white daughter, unused to the powerful emotion expressed in a Black church they have gone to in support of her black friend, is overcome by conflicting feelings and faints. In adolescence, when the two girls have migrated to their separate worlds, the daughter cries to her mother, “Why do I have to care?” The mother caresses, trying to calm, but is thinking: “caring asks doing. It is a long baptism into the seas of humankind, my daughter. Better immersion than to live untouched.” Through the use of sentence fragments and specific cultural grammar, what Toni Morrison and James Baldwin accomplished in illuminating the poetry of Black English, Tillie Olsen has done for Yiddish syntax and inflection, forcing us to read language as more than communication formed over centuries of use but as poetry, for poetry must in part be understood as a way of finding in ordinary speech imagery and allusions that dive deep into consciousness. Words accompanying the 1994 Rea Award for Distinguished Contribution to the Short Story: ‘She [combined] the lyric intensity of an Emily Dickinson with the scope of a Balzac novel.’

In 1969, having given birth to my first child, I was seeking desperately, futilely I began to believe, for a work that would describe the sudden plunge into the deepest love I had ever known, but also the body-wide fear and paralyzing guilt that could obscure that love into periods of fog and confusion, into rages and weeping I neither recognized nor understood. Tillie Olsen gave me language to begin to name them.

In about 1975, soon after I had published my first book, The Mother Knot, a memoir about the transformational experience of giving birth and learning to mother, I received a gift from Tillie—a copy of her novel, Yonondio, From the Thirties. By then, I had read all her fiction with a wave of relief—like those enormous ocean waves at high tide which, though large, can be gentle if you are out far enough—your body sails over them, safe and amazed as you watch them crash into shore. So, reading her fiction, I was witnessing the crash—reading about the complex and powerful feelings in being a mother, far enough out not to be hurt, yet awestruck by the power of the wave. Tillie Olsen’s poetry and courage would enable me to participate in a sea of change over a lifetime of writing and teaching: the maternal voice, finally not trivialized or sentimentalized or falsified, not restricted to a “how to” or a pediatric manual mostly written by male doctors; instead, so truthful and eloquent she was driving this long-buried voice into literature.

In my now yellowed and fading paperback copy of Yonondio there was something I would learn lay at the very heart of her being. In the middle of the novel, she had inserted a note. In her characteristic tiny script, which I can hardly read today, stuck to the page with a nice red star (this was before post-its!), she crossed out a paragraph and, in the margins, wrote a note to me about how she would rewrite it. “Omit” she wrote, and added several question marks in dark black ink.

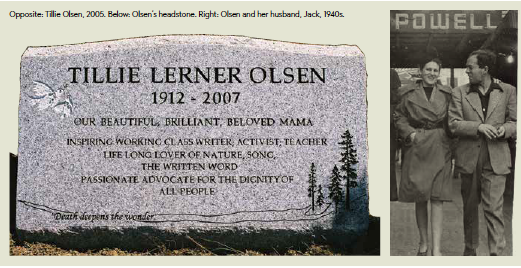

Tillie Olsen was born Tillie Lerner “in a tenant farm in Nebraska, the second of six children of Russian Jewish immigrants who left their homeland after involvement in the failed 1905 revolution. She grew up in Omaha, where her father worked as a painter and paperhanger and served as state secretary of the Nebraska Socialist Party. … In 1929 she embarked on what would be thirty years of low paying jobs (hotel maid, packinghouse worker, linen checker, waitress, laundry worker, factory worker, secretary).”

These words were written by two of her daughters, Julie Olsen Edwards and Laurie Olsen, significant because one of Tillie Olsen’s defining values was to pass on beliefs to the next generation—first to her own children, then to other writers in whose work she saw a sign of necessary voice, some in danger of being silenced by economic and political constraints. She spoke out for labor, against Apartheid and racism, against war, for women’s rights, for the protection of the earth. Like most dedicated activists, she could be fierce in her convictions, in her fury at injustice. But this was all very familiar to me. I had been raised in a family of Jewish American Communists, and this was one piece of our history, I think, that drew us together: we knew the faults of the old left— their righteousness, yes, and how wrong they were in some ways, but also the beauty of the core beliefs, the brilliant core always shining at the center of everything Olsen wrote.

Her essay, “Silences” (in a book by the same name), about the sources of literary silence through centuries of writing, is a sustaining work for every writer I know. She writes of the barriers to fullness of voice, constraints at times to coming to voice at all:

She quotes Herman Melville: “…the calm, the coolness, the silent grass-growing mood in which a man ought always to compose— that I fear, can seldom be mine. Dollars damn me—what I feel most moved to write, that is banned,—and it will not pay.” And she notes how Joseph Conrad described his creative process, unaware of the economic and gender privileges enabling him: “…I suppose I slept and ate the food put before me …but I was never aware of the even flow of daily life, made easy and noiseless for me by a silent, watchful, tireless affection.”

Photos Courtesy of Julie Olsen Edwards

Like Virginia Woolf imagining Judith Shakespeare, who as a woman could never have brought to life her genius supposing she possessed it like her actual brother, Olsen wrote of our great human loss—the lives that never came to writing, “among these, the mute inglorious Miltons: those whose waking hours are all struggle for existence; the barely educated; the illiterate; women.”

Olsen reminds us that for centuries women writers who created good and great work almost all never married, never had children, wrote under male pseudonyms— until the small trickle began in my generation, and now the whole earth begins to fill with women’s stories as some—more than before but still not enough—emerge into print.

I am seeing her now—we are walking through the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City—she is pointing out patterns in color and shape, the portraits that so compelled her; and always, no matter what I was writing at the time, she is asking me about my children—how are they, she wants to know—how old are they now? It was often my portrayal of mothers and children she commented on in my work, the complicated layers of motherhood, the “amplitude” she called it.

It was her own amplitude that enabled many writers of my generation to begin to heal the split between our writing/artist selves and ourselves as mothers, and in imagining that healing begin to glimpse the nature of the disease that had split us, turning being an artist and a mother into inherent contradictions. She never minimized the effort, knowing the battles that accompany such a desire, and she wrote the history for us, let us know by her own honesty and specificity that we were not alone. But “Nobody,” she told me during one conversation about motherhood, “has a harder time in our society than a mother who is trying to make it alone.”

Olsen had a husband, Jack Olsen, a union organizer, waterfront worker and educator with whom she raised her four daughters and shared her life until he died, but her first work wasn’t written until her children were finally in school. She still worked a daily job, so it is not disembodied imagination nor an accident of inspiration that the first line of her first published work is “I stand here ironing.”

A mother, overworked and suffering feelings of guilt toward her daughter who is having trouble in school, the eldest, the one who she depends on to help care for the others—the story ends with the final lines so many of us know by heart: “ So all that is in her will not bloom—but in how many does it? There is still enough to live by. Only help her to know—help make it so there is cause for her to know—that she is more than this dress on the ironing board, helpless before the iron.”

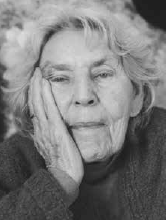

Opposite: Tillie Olsen, 2005. Below: Olsen’s headstone. Right: Olsen and her husband, Jack, 1940s.

Photos Courtesy of Julie Olsen Edwards

In the late 1970s I traveled to Santa Cruz, California, to interview Olsen, an assignment from a women’s magazine which for a short time was hiring progressive, feminist editors. The interview was never published, but we talked for a full day. Her grace and intimacy subdued my intimidation as she showed me the many photographs of artists and writers displayed on her crowded book shelves, talked of her love for her daughters, her own history, of the injustice and sorrows of the world. We were then in the midst of the War in Vietnam, of the American struggle for Civil Rights, a time of horror and hope. When I think about that day in her living room, then sitting out on her lawn as we drank tea, I can still remember my walls breaking down from the force of her passion, and I listened and responded from that deepest part of me—the “farness, the selfness”—her words from Yonondio—for she talked about the “terrible importance” to the writer of encouragement, of recognition.

Break those words down to their literal meanings to comprehend the full force of her empathy—for she had known a lack of courage and thus the need for encouragement, especially from other writers, and she had known the enormous task of re-thinking— recognition—from a life centered on providing and caring for others to a life of writing, which often means putting oneself and one’s own needs first—contradictions to be experienced and explored but never to be erased. And she was concerned about our sons—though she had daughters—and how we raise them. Talking of a little boy she had read about: “You see the process here of this imaginative little boy having to become this tough avenging person—what happens is that he has to reject his mother and identify with his father—and it is an every-day pressure on him, the shaming, and sometimes actual brutality. How do you raise a certain kind of boy against this?” she asked me.

Speaking of the changes in conceptions of fatherhood we were immersed in then, she insisted, “what made the difference to a new kind of fatherhood even possible for some was the change from the six to the five-day working week, and the difference between an eight hour and a seven-hour day. Anyone who has worked seven instead of eight hours knows how much more of you is left over.”

In “Hey Sailor, What Ship,” the title an italicized elegiac retrain that is repeated throughout the story, she imagines a kind of righteous brotherhood: “Once an injury to one is an injury to all. Once, once, they had to live for each other.” At the close of the story is the dedication referring to the Spanish Civil War against fascism:

“For Jack Eggan, Seaman, 1915–1938.”

In “The Strike,” a piece of experimental journalism published in Partisan Review, a striker writes: “Forgive me that the words are feverish and blurred …but I write this on a battlefield.’ If feverish evokes passion, blurred suggests overlapping shades of color or meaning yet to be clearly distinguished. Tillie Olsen writes all her work from this battlefield, fighting injustice with stories and brilliantly honed insights, digging into layers of language—breaks and interruptions suggesting the deep divides and steep descents into thought and feeling not yet named but glimpsed, sensed, and if the “conditions” of creative work are present, at times able to be heard in the mind, or spoken aloud, then written onto the page.

Jane Lazarre’s most recent book is a memoir, The Communist and The Communist’s Daughter. She has recently completed a collection of poetry, Breaking Light.

This essay was written as an Introduction to the new edition of Tell Me A Riddle in Spanish by Las Afueras, Publishers. The English edition of Tell Me a Riddle is published by the University of Nebraska Press and includes an Introduction by Rebekah Edwards and a Biographical Sketch by Laurie Olsen and Julie Olsen Edwards.