The New Questions

A series of harassment allegations against prominent Jewish sociologist Steven M. Cohen, exposed in the Jewish Week last summer, sent the Jewish academic and institutional world reeling—not just because of the personal #MeToo stories that shocked, but because of the influence Cohen had wielded setting priorities for so many communities. He was the individual most closely connected with major Jewish demographic surveys done over the past 20 years or so—including the Pew study of “Jewish Americans” which was a hot topic in 2013. In particular, feminists have been challenging an agenda based on data from the questions asked in these massive surveys, especially their focus on intermarriage as a primary threat to “Jewish continuity.” What were the questions not being asked because of Cohen’s own biases, and those of some of his academic peers?

Why We’re Asking

As many feminist scholars have noted, the questions asked on surveys carry a bias of their own, especially when answers can only be either/or. A greater focus on qualitative, rather than quantitative results, as well as a broadening and redefining of certain key terms—like “continuity” or “support for Israel” or “observant”—could yield some fascinating new truths about what Jewish life looks like today.

Keren McGinity is a Jewish gender historian who specializes in American Jews and intermarriage—and was the first to speak out with her own allegations about Cohen’s inappropriate behavior. She speculated with Lilith about the broader policy ramifications of this reckoning that moved from the personal to the institutional.

“I see this as a positive, the questioning of the validity of the framing for these very large community studies,” she told Lilith. “Now, it’s time to take a step back, and say ‘let’s re-think our assumptions, let’s open up the discussion so that more people can participate.’

“I think there’s almost been a trend of boiling things down, an obsession with statistics—as though numbers can explain everything,” says McGinity. “With all due credit, numbers are important—but I think of them as a frame; then one adds the qualitative body, flesh, skin.”

One built-in problem is that surveys, by their nature, often require people to check a single box, choosing one side of a binary. “People are not simple,” says McGinity. “There are many more intriguing behaviors and spirituality and creativity that numbers simply do not capture.”

Most importantly, McGinity is one of several feminist voices calling for these urgent conversations to include more voices, a turn away from the “single expert” model to include a broader group of people from different disciplines weighing in on a given issue.

“There’s only benefit to be gained from sharing the limelight,” McGinity declared.

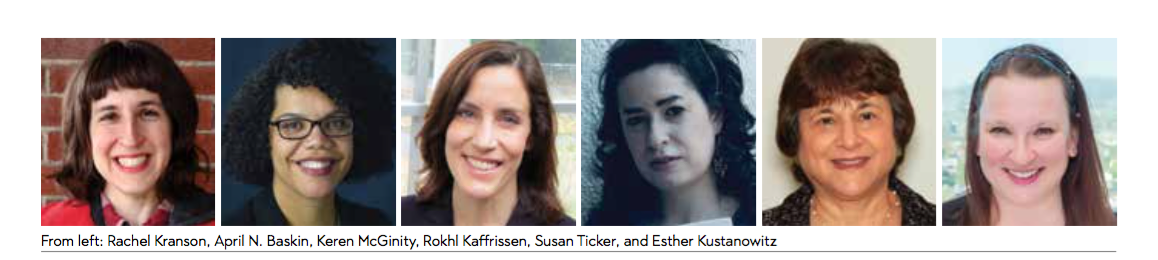

In that spirit, Lilith gathered a panel of feminist experts from across fields—activists, writers, educators and academics—to start asking the new questions. What would they like to learn from any new demographic surveys of Jews?

The Participants

APRIL N. BASKIN, the principal of Joyous Justice Consulting and also serves as the Racial Justice Director of the Jewish Social Justice Roundtable. She is the Union for Reform Judaism’s immediate past Vice President of Audacious Hospitality and host of the first season of their latest podcast, Wholly Jewish. Before founding and developing the URJ’s department, she served as the National Director of Resources and Training at InterfaithFamily.

ROKHL KAFFRISSEN, journalist and playwright in New York City. Her work on new Yiddish culture, feminism and contemporary Jewish life has appeared in publications all over the world, including Haaretz, The Jewish Week, The Forward, Alma and Lilith. She conducts the biweekly Rokhl’s Golden City column for Tablet, focusing on Yiddish and Ashkenazi life in all its incarnations.

RACHEL KRANSON, associate professor of Religious Studies at the University of Pittsburgh. A specialist in the history of American Jews, she is the author of Ambivalent Embrace: Jewish Upward Mobility in Postwar America (University of North Carolina Press, 2017) and, along with Shira Kohn and Hasia Diner, the co-editor of A Jewish Feminine Mystique?: Jewish Women in Postwar America (Rutgers University Press, 2010). For many years, she has also been a Lilith contributing editor.

ESTHER KUSTANOWITZ, a contributing writer at the Los Angeles Jewish Journal and a columnist at J. The Jewish Weekly of Northern California. She was founding editor at GrokNation.com and has consulted with dozens of Jewish organizations. She is working on a book about life after loss, and is a casual scholar of Jewish references and storylines in TV shows.

SUSAN TICKER is a strategic advisor, mentor and change agent for synagogues, day schools, camps, and other nonprofits. For almost a decade, as a communal consultant at The Jewish Education Project, she guided professionals and lay leaders to develop innovative education models for all ages.

NAOMI DANIS, is Lilith’s managing editor and has been compiling the resource pages of Lilith for three decades. Her newest picture book is While Grandpa Naps.

SARAH SELTZER, Lilith’s digital editor and a writer based in New York. She has written and reported on various progressive issues this year at The Nation, TIME, Cosmopolitan, Refinery29, Jewish Currents and Jezebel.

SUSAN WEIDMAN SCHNEIDER is Lilith’s editor in chief, and one of the magazine’s founding mothers. She’s the author of Jewish and Female: Choices and Changes in Our Lives Today and Intermarriage: The Challenge of Living with Differences Between Christians and Jews; and co-authored Head and Heart, a book about money in the lives of women.

The Conversation

SUSAN WEIDMAN SCHNEIDER: We’re here because we know that a lot of things were not ever getting asked in demographic surveys, partly because the people who want to know certain kinds of information were not in on the planning process. Though I’ve been addicted to these surveys for many many years now, there are so many questions I’ve never seen asked. Once, for instance, Lilith wanted to know: are Jewish women remaining single through their childbearing years for longer than women from other groups? Male demographers said, “That’s impossible because of primacy of marriage in Jewish culture and religion.” So we asked: Can you just take a look at your findings through this gender lens? They looked at the data. And—surprise—found that Lilith’s hunch was true, in part because Jewish women tend to stay in school longer and postpone marriage, meaning that their “field of eligibles” might shrink, and so forth. Just one tiny example of how the picture changes when women ask the questions.

So: if you were the demographers, what would you ask?

RACHEL KRANSON: First, we have to consider who is looking for a particular piece of information, and why. As a historian, my last research project was on the ways that American Jews understood their upward mobility in the years after WWII. I looked at the sociological surveys, which told me the percentage of Jewish men who earned a professional degree or brought home a middle-class salary. This was certainly of interest to communal leaders who made decisions about allocating communal funds, or who may have wanted to celebrate the Jewish adaptation to American, middle-class norms. But as a historian, and particularly as a historian who pays close attention to gender, I could not leave it there. I had to look at more qualitative sources to discover: What did this upward mobility actually mean to people, and how did it affect their attitudes toward politics, religion, and gender? We always have to think about who is asking the questions, what are their biases, and also break it down: what are the terms they are using, and why?

APRIL BASKIN: It’s so important to have that specificity. I also think that when it comes to any studies having to do with race and ethnicity—there’s a socioeconomic valence, there’s an implicit bias when we do ask. Or we just miss it entirely. I was a respondent in a Boston survey and they didn’t even ask about race and ethnicity.

SUSAN WEIDMAN SCHNEIDER: And to get more specific: are multiracial families multiracial through adoption, through parents of different races? What was the path to forming this interracial household?

APRIL BASKIN: There’s not a lot of great data around who has Mizrahi or Sephardi heritage. Right now, when I’m doing this work, I say estimates are 10 percent, but….

RACHEL KRANSON: I want to help historians of the future understand the assumptions behind the terms we use. For instance, when we use the term, “Jews of Color,” who are we including and why?

APRIL BASKIN: Yes, so often these days we harken back to the civil rights movement. I wish I could know now, how did the support and non-support for civil rights break down demographically and denominationally?

ROKHL KAFRISSEN: I have a personal agenda in these discussions—I’m a Yiddishist and I’m always thinking about how things like language, ethnicity and heritage get erased by communal apparatus, like surveys. The Pew study in 2013 wasted time on questions like “Do you think Obama is doing a good job?” There was not one single question like: Do you identify as Ashkenazi, Sephardi or Mizrahi?

NAOMI DANIS: And the questions that relate to those ones. What languages are you speaking at home? That can tell you so much, whether it’s Spanish, Yiddish, Farsi, or Hebrew.

ROKHL KAFRISSEN: I would like to go further and know what language did your parents speak? What language did your grandparents speak? Where were they born? Given the way that demographics are changing, the majority of American Jews are going to be intermarried. We’re going to need a way to define and categorize those combined identities that are going to be the majority.

RACHEL KRANSON: A pet peeve I have that comes up in these surveys is a common fixation on households as a unit of measurement. Think about everything that gets lost! If you ask whether a household puts on a seder every year, that doesn’t tell you about individuals who make up that household. Who decides that there will be a seder? Who leads the seder? Who cooks and serves?

SUSAN WEIDMAN SCHNEIDER: “Family” is a pet peeve along with “household.” There are people who are marrying later, living alone, living in uncategorized household arrangements.

APRIL BASKIN: Anecdotally, the non-Jewish partner in interfaith family is often the initiator of the Jewish ritual. I would like to know if that is a larger trend—that could mitigate the panic about interfaith marriage.

NAOMI DANIS: We need more lines of inquiry that ask: What are the strengths of interfaith families?

SUSAN WEIDMAN SCHNEIDER: And, being binary for a moment, does it matter in those instances if the non-Jewish partner is male or female?

ESTHER KUSTANOWITZ: And people without partners are always left out, especially if they do not have children. If this sounds like a personal example, it very much is. I went to yeshiva day school, and Camp Ramah, and I have been in the Jewish community all my life. And I have no place in the Jewish community as a single woman in my 40s. For years I’ve been hearing that there are more single women than single men, but that’s not helping. The data isn’t here, and it gets no money and attention—so the prevailing assumption remains that Jews want to get married and want to have children. But I’m not convinced that even if there was a study on 40-something Jews, the community would do something for them.

SARAH SELTZER: And beyond just single vs. partnership, how do we categorize people who are living in radical queer households? And include families? Or what about single people living with platonic roommates into later decades? How many Jews are openly polyamorous? We can assume because Jews live in urban areas, and tend to be university-educated, that they are in the vanguard of new social trends. But we don’t know if that’s the case at all.

ROKHL KAFRISSEN: I’ve started having seders in my house, with two of my friends who are queer; one of them is not even Jewish. I am not sure how I would answer if someone asked me a traditional question: “Does your household have a seder?” I’d say, “Yeah, where do we even begin?”

SARAH SELTZER: Going back to the living arrangements, it extends to observance: many millennials are not connecting to Judaism through shul or even nonprofits that might normally be tallied. Instead they’re involved in the arts, activism, informal minyans that are not affiliated, or maybe even socialist secular humanist study groups.

ROKHL KAFRISSEN: There’s an economic piece too, asking how student loan debt correlates with people not getting married and having kids. I wonder if there’s a correlation between states with the highest levels of student loan debt and the percentage of Jews in that state?

SARAH SELTZER: And how are things like student loan debt affecting people’s politics?

SUSAN TICKER: We need questions that get ahead of the curve on socialism in the Jewish community.

ESTHER KUSTANOWITZ: I’d love to know what contemporary Jews’ attitudes are towards information and media. I’m interested in where Jewish women are getting their news. Who is producing our news?

ROKHL KAFRISSEN: And relatedly, on what issues are Jews reading and engaging specifically as Jews? When are they turning to Jewish media, for instance? And what has the Jewish investment been in considering themselves as marginalized? When are they identifying with the mainstream?

NAOMI DANIS: I’d like to know where people get whatever Jewish literacy they have. From childhood schooling? Adult learning, whether formal or informal? From media?

ESTHER KUSTANOWITZ: Going back to defining the terms, I want to know who defines themselves as a Jewish feminist and what that means? And an idea like intersectionality, which we often talk about without understanding. How does feminism relate to issues like mental health and body image in Jewish families?

SARAH SELTZER: One of the findings from the Pew survey that stuck out was that more Jews viewed having a sense of humor as intrinsic to their identity than, say, synagogue attendance.

ROKHL KAFRISSEN: We need more qualitative surveys that ask questions in that vein, but don’t prime respondents to answer with something as broadly appealing as, say, having a sense of humor.

SUSAN TICKER: I appreciate the way so much of this comes down to methodology. If researchers say—as some have—you only need 39 people to respond, and once you get past 39, the data will repeat, and findings will be confirmed. If you can be that cavalier about methodology… I want to raise the question of what other biases may be at work.

SUSAN WEIDMAN SCHNEIDER: Do you think a reason, beyond logistical, that some of this hasn’t been crowdsourced—and beware the generalizations—is that Jews are such believers in expertise? But that means “leaders” are making decisions for others whose lives are very different from theirs.

SUSAN TICKER: I think a related line of inquiry is: if we hadn’t been so focused on continuity and survivalism in recent years, what questions would have been asked?

RACHEL KRANSON: I wonder if we couldn’t flip this model of having a few researchers asking a few questions. Have the researchers ask their informants, “What do you think the questions ought to be?” as we are asking tonight? There are probably pragmatic reasons this hasn’t been done, but that crowdsourcing model might generate much more creative and provocative and interesting questions.

New Questions from Keren McGinity

1. What does doing Jewish look like — rather than being Jewish? as with my own research, this is not about how Jewish someone is, but about how are they expressing being Jewish?

2. How do gender and gender roles play out in same-sex interfaith and/or interethnic relationships? In interfaith families, what ways do the gender of the Jewish parent and the gender of the child influence the way the child engages in Judaism?

3. What makes a successful/happy/healthy (you can add the words “Jewish” or “Interfaith” here) partnership and family? We’ve been focused on making sure that they’re Jewish, but what about making sure that they’re happy, and love each other?

4. I’d like to see a question about the longevity of partnerships that are committed to egalitarian ideals (although we haven’t fully achieved it)?

5. What does it mean to be un-partnered and single for Jews over the age of 30, 40, 50? Are there unspoken and unanalyzed advantages, benefits and joys to this lifestyle? What kind of communities do these Jews find and form and keep?

6. A question about #MeToo—for women and men who have had experiences with harassment (because all genders can be manipulated and exploited). How does this affect their engagement with communal life and ritual?