The Centenary of Dr. Mária Lakatos

Dr. Mária Lakatos changed the world, quietly—despite Nazi and Communist persecution. A Budapest-born Jewish doctor and Holocaust survivor, Lakatos did groundbreaking work in the fight against tuberculosis, the biggest infectious-disease killer in modern times until the advent of Covid. And her kindness to persecuted artists with TB led to her becoming, accidentally, a noted art collector.

Mária Lichtmann, born in 1922, was a bookish only child from a middle-class Jewish family, with aunts and uncles who doted on her. In the summer of 1938, while holidaying on the Danube with her family, she met her future husband, Lászlo Levendel; they married after her high school graduation. Just months later, Levendel was summoned to forced labor camp, where Jewish men were used as slave labor.

About 100,000 Hungarian Jewish men were sent to these hells, and eighty percent perished, either from what the Nazis called “annihilation through work” or outright murder.

When her husband was on a brief leave in 1943, Lichtmann became pregnant with their first child, Júlia, born four days after the Nazi occupation of Hungary, in 1944. From that moment on, Lichtmann went into hiding with her daughter in apartments that were bombed, and in the basements of buildings continually searched by the Arrow Cross/Hungarian Nazi party, as they hunted Jews and sent them to their deaths at Auschwitz.

Sometimes she moved daily; often she did not know the whereabouts of her family, many of whom were transported and murdered in the death camps. In January 1945, against all odds, Lichtmann and Levendel were reunited in Budapest, moved to Szeged, and attended medical school. After all of the carnage, brutality and terror of the war, their lives became devoted to healing.

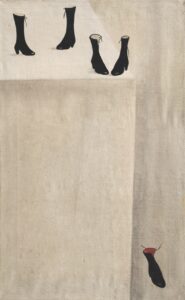

Lili Ország, “Black Shoes,” 1955, oil on canvas

The postwar years were a time of both euphoria and exhaustion. Hungary was finally at peace, but any dream of becoming a liberal democracy was short-lived. In 1947, the Communist Party seized power and shut down all opposition. The ensuing show trials were swift, and punishment was merciless. Levendel was swept up in the Red Terror and banished to a pulmonary hospice in a small regional town for nine months. Left alone with her young daughter and her son Ádám, born in 1947, Lakatos was in peril. She found work as a military doctor, and changed her name from Lichtmann to Lakatos–both to protect her family from antisemitic attacks, and perhaps also to distance herself from her husband in a bid to appease her tormentors from ÁVH, the Hungarian secret police.

And they were tormentors. For months on end, Lakatos was forcibly taken to interrogations in the middle of the night, not knowing if she would be returned home to her children. She was relentlessly exhorted to divorce her husband, but refused. In 1951, Dr. Levendel took up a position at the Korányi Sanatorium in Budapest, where in 1954 he was joined on the staff by his wife. Together they spent the rest of their working lives healing those afflicted by tuberculosis, a plague that stretches 9,000 years back in time in humans; and 17,000 years in ancient bison.

In 1882, when Dr. Robert Koch announced his discovery of the bacteria that cause Tb, the disease was killing one in every seven people living in Europe and the US. So deep was the ignorance about Tb that its highly contagious nature was not understood, and the disease was believed to be hereditary.

Unsurprisingly, TB flourished among the urban poor whose living quarters were overcrowded and far from sanitary. Mountain-top sanatoriums were hailed as the cure, spurring a building frenzy across the U.S. and Europe, the most famous one being Schatzalp in Davos, which was immortalized in Thomas Mann’s 1924 novel The Magic Mountain. But it was not until 1943, with the development of the antibiotic streptomycin that the first real successes in the fight against Tb were achieved.

However, in post-war Hungary, streptomycin was still so rare and expensive that it was only dispensed via a triage committee, and then only by the gram. Treatments were slow and lengthy, relapses occurred, surgery and extended stays at the sanatorium were often required, all giving the doctor-patient relationship time to develop. Lakatos was Head Physician at the Korányi Sanatorium, in the leafy Buda hills, where she and her husband treated patients in a holistic manner that considered not only the pathologies of their disease, but also their psychological and emotional wellbeing.

They treated people without homes, as well as alcoholics with TB—among the most marginalized members of society. With a reputation for compassion, they developed a huge following among the artists of Budapest, who flocked to them for treatment and in return gave them art. What resulted was one of the most spectacular collections of modern art in Hungary, which since 1998 has been housed in the Municipal Picture Gallery-Kiscell Museum in Budapest.

In 1954, Dr. Lakatos began to deepen her interest into rheumatology, pneumonia and breathing rehabilitation. Physiotherapy was at that time still an emerging branch of the healthcare system in Hungary, and among its earliest proponents were modern dancers, who understood its benefits. Many of these modern dancers were unable to practice their art in the highly repressive post-war era, where every aspect of life was regulated.

Hardline Communist propaganda was everywhere, and whether in the world of art or dance, all output was policed and censored. The choices for nonconformists were stark: make work in the state-sanctioned Socialist Realist style, or become invisible. In the world of art, some acceptable tropes to celebrate were: the fecundity of the Communist woman, the physical power of the Communist worker, and the cherubic idealism of children. In the world of dance, the emphasis was similarly placed on homogenization, not individuality, using motifs from national folklore and narratives that emphasized the moral superiority of the Communist world.

Dr. Lakatos’s collaboration with the avant-garde dancer and physiotherapist Ágnes Kövesházi Kalmár began in 1954 and continued for decades. Kalmár had both an intimate understanding of anatomy from her dance training, and also Tb. Together they developed new ways to strengthen patients weakened by the disease, particularly post-surgery. These methods would prove so successful that Lakatos was granted permission to travel extensively to present her work, both within the Communist Bloc and to the West. She published widely, including the influential book Breathing Rehabilitation (1972), co-authored with her husband.

It was through Kalmár that Lakatos and her husband would meet many of the artist-patients who came to the sanatorium to be treated for Tb, and whose art would form the core of their collection. Many were Holocaust survivors, and trailblazing modernists who refused to toe the Social Realist line. They were blacklisted by the regime, forbidden from exhibiting their work, or earning their living as artists until the slow cultural thaw that began in the 1960s. The women artists in the collection, among them Margit Anna (1919–1991), Júlia Vajda (1913–1982), and Lili Ország (1926–1978), would be overlooked until the final years of their lives.

In “Loneliness 1967,” two “socially distanced” chairs are drenched in a blazing sunset, and a solitary figure sits on one of them, deep in contemplation. This painting conjures the isolation of infectious disease, an experience that collectively and individually we have all known these past three years with Covid.

“Black Shoes” is a heartbreaking tribute to the thousands of innocents who were shot dead into the Danube River between 1944 and 1945 by the Arrow Cross militia.

When I interviewed Dr. Lakatos’s daughter, Júlia Levendel, I asked what she thought was her mother’s greatest achievement— and she said it was that a Jewish woman could accomplish so much in such a restrictive era. Whilst the Communist state did bolster the position of women in society by providing free education and childcare, access to these opportunities was routinely stymied by the Party for perceived “disloyalty.” As for the profound trauma experienced by the tens of thousands of survivor Jews who remained in Budapest after 1945, less than nothing was done to acknowledge, let alone alleviate their anguish. The whitewashing and blame-shifting continues to today.

The Korányi Sanatorium still exists in the Buda hills, and tuberculosis rages on unabated, in spite of medical advances. Hungary is different from what it was in Dr. Lakatos’s day; there is greater freedom, and there is also far less freedom than had been hoped for with the collapse of European Communism in 1989.

In April 2022, Viktor Orbán, Hungary’s far-right leader, cemented another four years in power by continuing to erode the pillars of democracy. The dreaded nineteenth-century dictum Kinder, Küche, Kirche (Children, Kitchen, Church), has once more reared its retrograde head in Hungary, where churches are propped up over hospitals, and women are the most poorly represented in government in all of the European Union. In an irony that will not be lost on Lilith readers, a July 2022 State Audit Office report found that over the past decade, more women than men had enrolled in Hungary’s universities, and that this posed a threat to the economy.

Yet Dr. Mária Lakatos’s centenary is a timely reminder that pioneering progress is forged even in the most hostile of environments. To remember those trailblazing women neglected by history is not just an inspiration, but an obligation.

Nicole Waldner has a special interest in modern Hungarian history and art, with work forthcoming in Jewish Renaissance in 2023. (Find her at nicolewaldner.com)

Margit Anna, “Loneliness 1967,” oil on canvas.