The Avant-Garde Artists She Hangs on the Walls

A good curator’s hand might be unseen in an initial look around an exhibition. Yet the curatorial vision enhances the pleasure of seeing works of beauty and imagination, and shapes how viewers encounter the art—and can even reshape their outlook.

In the Fall of 2018, after more than 30 years of distinguished work including the launch of 120 art exhibitions, curator Laura Kruger was granted an honorary doctorate at Hebrew Union College—Jewish Institute of Religion for her visionary leadership. As the curator of the art space in the College, she earned the degree for her ongoing connoisseurship, imagination, expertise and devotion to the Reform seminary and its museum.

A woman of passion for the arts and the ever-growing collection of artists she has shown and promoted, Kruger knows what she likes, can explain it well and loves doing that. Talking with her is like a class in art appreciation with a master teacher. Her definition of Jewish art is broad and inclusive. As she says in an interview in her office a few doors above the recently renamed Dr. Bernard Heller Museum at HUC, “I don’t define Jewish art by the birth certificate of the artist. I am intrigued in how a person uses Jewish heritage.”

Over the last decades she has seen this art become more self-assured. “What passes for Jewish art in a lot of places is something with a Magen David [star of David] or menorah,” she says. “I’m not talking about that. I’m interested in someone who connects with his or her faith, who reads, studies, who feels comfortable stating something.

“Can I define a Jewish aesthetic? No, because I don’t want to. I don’t think there’s a Jewish style of painting. I think there is an ethos in choosing a subject and perhaps an implied message from the subject that’s intuitive to the artist.”

In her 2018 book, Curatorial Activism, curator and arts writer Maura Reilly advocates for rule-breaking exhibitions that challenge identity-driven social issues. Kruger’s most recent shows, addressing issues like home and homelessness (and the thin line between), climate change, sexuality and the nature of evil challenge viewers to think anew, and in the context of, but not limited to, Jewish identity. Her shows are less about art history and academia, and more about new perspectives and new ideas. Her activism extends to inviting a broad range of artists to participate, reaching across ages, backgrounds, artistic genres, materials and religious perspectives (and all are not necessarily Jewish); she’s proud of the diversity she presents.

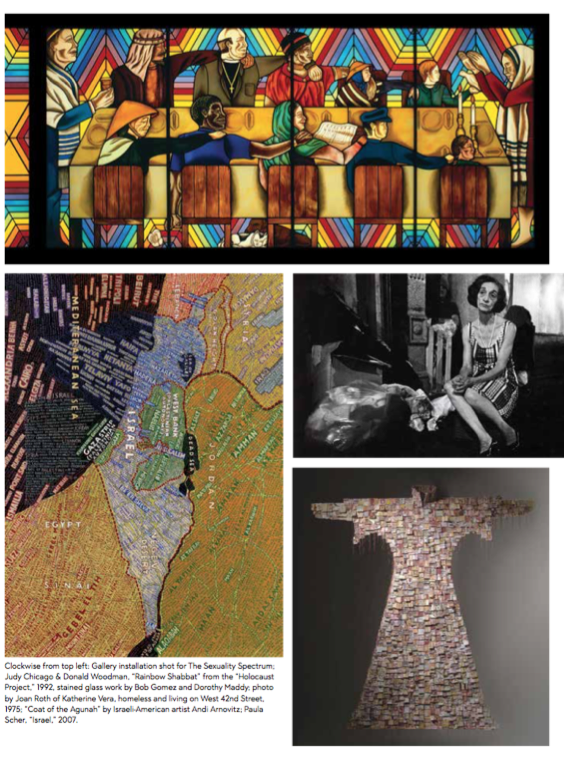

As a curator, Kruger is energetic and courageous. In the h.u.c. show “Envisioning Maps,” which was highly original in its juxtaposition of work showing land, space and terra incognita (the spaces on earth not yet imprinted), she brought together paintings and sculpture that used actual maps or the concept of maps, raising important questions about history, borders, migration and ecological disaster. Paula Scher’s painting “Israel” is covered with names of places in the shape of the State of Israel; although not meant to be read as a map, perhaps it suggests how words create history. The power of this exhibition was in how Kruger turned the concept of a map around and around, probing deeper, as she included a piece about an eruv, or symbolic enclosure (“Venice Eruv” by Ben Schachter), the planet’s fragile state (Ann Perry’s “Lamentations: Continental Drift”) and Karen Gunderson’s depiction of what the sky might have looked like to the Jews of Denmark on the night in 1943 when they were to be rounded up and sent to concentration camps, but were instead offered refuge by local citizens (“Constellation 4: Copenhagen”).

As she writes in the introductory essay to the catalog, “Jewish maps defined more than places of Jewish ownership; they encompass the places where Jews once lived and were forced out by pogroms, inquisitions, and the Shoah. They include the maps of memory of immigrants, Biblical Israel, and modern Israel.”

In her inclusiveness and wide-ranging views, Kruger shows again and again the diversity of Jewish views on a single subject, and the many ways to be Jewish and embrace Jewish values.

And in another inspired collective show, “Paint by Number,” Kruger writes that “Numbering creates a scaffold of order and continuity—virtually everything we are, do, and interface with is a number.” She cites historical dates, Biblical stories, the meaning of counting and symbolic numbers; the exhibition title evokes, with some irony, the preprinted artist sets popular in the 50s where people would apply color between the lines in designated areas, and the freedom of artists to reject any such rules.

Unabashedly, she believes that a museum, an exhibition, must have a moral core. She has no problem pushing Jewish values. We meet in the office she shares with colleagues, filled with art on the walls, Judaica on the shelves and still-wrapped artwork sent for an upcoming show.

“My job is a couple of things, to select a subject that is broad enough to embrace what needs to be said Jewishly in this moment in time and the artists who are strong enough to maintain their own voice in a group dialogue. That’s what the show is about, not an extended sentence from wall to wall, not a cacophony, but a continuity that leads to another thought to another thought,” she says.

“The artists address Jewish issues, not necessarily in overt Jewish ways but in deeply regarded Jewish ways.”

In 2007, Kruger did a show featuring the work of an artist who has become a good friend, “Judy Chicago; Jewish Identity.” Chicago’s painting “Rainbow Shabbat from the Holocaust Project(1992)”, a stained glass piece that is part of her “Dinner Party” series, powerfully influenced the way Kruger thought about the Shoah. She thinks that the piece helps people confront their own nightmares, and also frees up those who didn’t experience the Shoah to talk about it. For Kruger, the painting also expands understanding of how inclusive a Shabbat table can be. Always, Kruger is interested in the rainbow, in making room for all.

Kruger sees art as part of the communal dialogue, making its own statements. More than a decade ago, in conjunction with the Jewish Women’s Project Ma’yan, she showcased a variety of artists’ renditions of Miriam’s Cup, helping expand Passover’s ritual possibilities. In the 2010 show “A Stitch in Time: Provocative Textiles,” Kruger presented “Coat of the Agunah” by Israeli-American artist Andi Arnovitz, who created a coat made of ripped-up digital scans of antique ketubot, or marriage contracts. The coat’s hand openings are sewn up—the wearer can’t escape—reminding viewers of the bondage many Jewish women still face in seeking freedom from recalcitrant husbands. Helene Aylon’s “The Book That Will Not Close,” featured in a 1999 exhibit devoted to the artist’s work, is an interactive, tactile piece in which tissue paper is interwoven onto every page of a Hebrew Bible. On those pages, she underlined in pink marker every phrase with a negative view toward women, or showed that their voices are absent. Though Aylon is underscoring that women are missing from the dialogue, still, she would not deface the actual pages.

Kruger sees art as part of the communal dialogue, making its own statements. More than a decade ago, in conjunction with the Jewish Women’s Project Ma’yan, she showcased a variety of artists’ renditions of Miriam’s Cup, helping expand Passover’s ritual possibilities. In the 2010 show “A Stitch in Time: Provocative Textiles,” Kruger presented “Coat of the Agunah” by Israeli-American artist Andi Arnovitz, who created a coat made of ripped-up digital scans of antique ketubot, or marriage contracts. The coat’s hand openings are sewn up—the wearer can’t escape—reminding viewers of the bondage many Jewish women still face in seeking freedom from recalcitrant husbands. Helene Aylon’s “The Book That Will Not Close,” featured in a 1999 exhibit devoted to the artist’s work, is an interactive, tactile piece in which tissue paper is interwoven onto every page of a Hebrew Bible. On those pages, she underlined in pink marker every phrase with a negative view toward women, or showed that their voices are absent. Though Aylon is underscoring that women are missing from the dialogue, still, she would not deface the actual pages.

Kruger’s vision is grounded in the present, tied to important themes of the day, although she is also drawn to how artists deal with memory, both personal and collective. She says, “I embrace art history in the most positive way I can. I’m not making comparisons between the past and present. The present is where we are now.”

“When people come in here expecting to see old-fashioned Jewish art, they are taken aback. We are not a history museum,” she says.

Among the many other artists she has shown in individual and group shows are Hanan Harchol, Tobi Kahn, Laurie Gross, Tamar Hirschl, Jacqueline Nichols, David Wander, Mark Podwal and Archie Rand. Over many years and exhibitions, she has shown the work of Nathan Hilu, who died in April at age 93—still painting until his last days—and personally championed the work of this outsider artist, trying to connect him with other galleries and museums, and also making sure that he had art supplies. She remains con dent that, posthumously, he’ll receive deserved recognition.

“I believe art is a language. People who cannot express themselves in words do it amazingly well in art. How the viewer interprets the art—that’s the conversation,” she says.

Joyce Ellen Weinstein, a painter who has known Kruger for more than 25 years, stops by the office and later says, via email, “Laura is an extremely thoughtful curator who is true to her vision and never takes her role lightly. I know that among my artist peers being selected for an exhibition curated by Laura is always a big deal and an honor.”

Importantly, through her group shows, Kruger has created a community of artists whose work may touch on Jewish themes, and who may not have been aware of one another. A few years ago, the Jewish Artist Salon got underway with the involvement of many of “Laura’s artists,” to further the work of building community.

Kruger sees her role, in part, as a guide, “able to articulate the essence of the artwork so that someone who does not have background either in the subject or the practice of art feels comfortable or understands what they’re looking at.” To that end, she takes great care in creating exhibition labels that are informative and non-intrusive—the labels might include quotes from the artist illuminating the work, or the back story of its creation. She recognizes that space dictates what a curator can do. For some of the artists, the museum also functions as a gallery, an opportunity to sell their work.

Kruger is a youthful 83-year old who still carries herself like the dancer she once was, at once elegant and down-to-earth. There’s something about being a curator that carries over into all that she does: Her home is filled with contemporary art, and she continually rearranges the works on her walls. She dresses stylishly with well-designed jewelry, and she can’t walk by a potted plant, anywhere, without making efforts to prune it, pulling o the dead leaves.

Her career path has been indirect, but she has had a robust, arts-driven life. She grew up in Brooklyn where her father was a businessman and her mother a commercial artist. She started studying ballet at age 6, and danced professionally from 1948 until she got married in 1956, dancing at Radio City Music Hall, the New York City Opera, and with the Ballet Russe of Monte Carlo. She danced while attending New York City’s High School for the Performing Arts and Hunter College—and also modeled wedding gowns for a Fi h Avenue bridal salon.

She then discovered her instinctive talents of selling—she loved describing what she saw, talking about the gowns, and she moved from model to salesperson. She flourished. As she says, “I just loved talking.”

Her first department store job was at the long-closed Arnold Constable. There, she “fell in love with the idea that you could change someone’s life—‘Just try this on’—or you could tell some-one why they looked good. I didn’t think of myself as a shop girl. I liked fashion.” Quickly, she was promoted and then recruited to join Bloomingdale’s, and then left to start her own business, a jewelry shop on Madison Avenue featuring handmade and one-of-a- kind pieces. For her, jewelry was like sculpture, or “wearing a piece of art.”

“Stores are about signage and display, how you position something within the store,” she says, sounding like she has been curating throughout her retail career. “I’m not certain that it can be taught— it’s like a play of energy between pieces, colors, shapes, subject matter. If you’ve been looking at art all of your life, you develop your own pattern of how you see.” While she can forget a line of a poem, she says, she never forgets an image or color tone.

Her interest in Judaica was sparked in 1978. The mother of a metalsmith entered her shop and took out a menorah her son had made. Kruger agreed to place it in her window, and a couple of days later someone bought it, so she brought in others. “That’s how I started in the Jewish world. Through that one menorah.” While she knew a lot about contemporary art, she didn’t know much about Judaica—yet. She also opened shops in department stores carrying her jewelry, and then her Judaica. A er 14 years, she closed her gallery and organized a gift shop for the Museum of Arts and Design, where her husband, Lewis Kruger, is now chairman emeritus.

Then, through a chance connection in the Long Island resort town where her parents had a home, she was introduced to Hebrew Union College and their collection of art and Judaica; at that point all of it had been donated to the college rather than collected intentionally. In 1994 she joined the sta of the College, and saw the opportunity to incorporate contemporary art into their educational efforts, eventually establishing the museum.

“I can’t imagine living without art,” she says. “Art is a big embrace.”

Sandee Brawarsky, an award-winning journalist and editor, is the culture editor of The Jewish Week and author of several books, most recently 212 Views of Central Park: Viewing New York City’s Jewel from Every Angle.