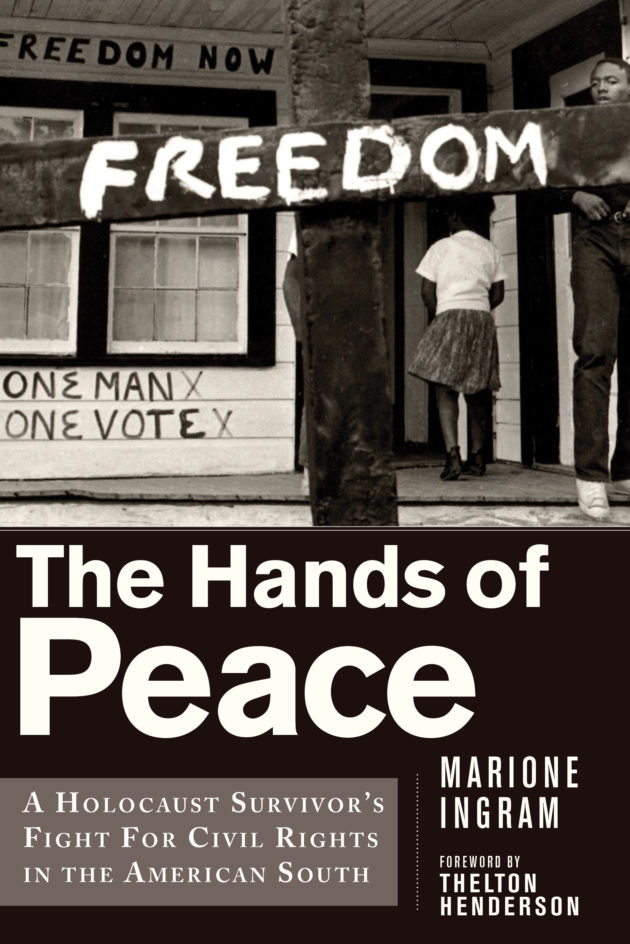

“The Hands of Peace: A Holocaust Survivor’s Fight For Civil Rights,” by Marione Ingram

Marione Ingram, a German-born Jew who survived the Holocaust and wrote about her wartime and postwar experiences in an earlier memoir, has now published her second, The Hands of Peace: A Holocaust Survivor’s Fight for Civil Rights in the American South (Skyhorse Publishing, $24.99). This is a struggle which she says called out to her personally as a Jew who had experienced murderous Nazi prejudice and racism first-hand. Although the large-scale events she chronicles here are familiar— the momentous1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the murders of civil rights workers Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner, the role of northern activists through 1964’s Freedom Summer and after — it’s the accretion of detail on a small, personal scale that brings a reader into the moment, the dropping of famous names aside (James Baldwin, Fannie Lou Hamer, and many more).

Marione Ingram, a German-born Jew who survived the Holocaust and wrote about her wartime and postwar experiences in an earlier memoir, has now published her second, The Hands of Peace: A Holocaust Survivor’s Fight for Civil Rights in the American South (Skyhorse Publishing, $24.99). This is a struggle which she says called out to her personally as a Jew who had experienced murderous Nazi prejudice and racism first-hand. Although the large-scale events she chronicles here are familiar— the momentous1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the murders of civil rights workers Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner, the role of northern activists through 1964’s Freedom Summer and after — it’s the accretion of detail on a small, personal scale that brings a reader into the moment, the dropping of famous names aside (James Baldwin, Fannie Lou Hamer, and many more).

Ingram, now 79, faced discrimination herself when she and a college-educated black friend (who could get work in a publishing house only as a bathroom attendant) try to rent an apartment together in Greenwich Village in the 1950s and faced the ubiquitous threat of violence when she went south to teach In a Freedom School.

The granularity of her descriptions, which often in memoir can make a reader feel excluded or put off, here succeeds in making the not-so-distant past very immediate. Even in comfortable Maryland suburbs, violent racism lurked close to the surface. In one vivid example, Ingram details what happened when she and her husband, in 1965, encouraged black friends to join them in their suburban community, just outside the nation’s capital:

For the next several weeks we were subjected to many remarkably inventive efforts to frighten and harass us into fleeing. Some of the events were so surprising and appalling that we were amazed that they were happening in an affluent community chock-full of high government officials, office-holders, professionals, and senior managers of every type of benevolent or public interest organization. Even our babysitters were threatened with harm for taking care of our son. Twice we returned home to find police and a terrified sitter. One Sunday morning, while we were walking with Sondra Dodson, a beautiful African American friend who had come to tell us she had decided to marry Bill Raspberry, the Washington Post’s lone black reporter, a police car came racing toward us, screeching to a stop inches away, then sitting there racing its engine until we walked away. We learned, because a friendly neighbor told us, that our tormentors had formed a syndicate to buy our rented house.

Fortunately I was at home and able to fend off a posse from the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, which had come to impound Orfeo, our thoroughly pampered standard poodle, in response to reports that we were cruelly abusing him. One of the most upsetting events occurred each day when the Good Humor truck arrived and neighborhood mothers would rush out of their homes and make a big show of buying treats for all the kids, conspicuously excepting Danny. Still we held our ground until an anonymous caller said that it was clear to them (whoever they were) that we were not sufficiently moved by what they had done so far and therefore they had decided to “go after” our son. Soon after the call, a car drove across our lawn toward Danny. I reached him first, snatched him up, and left that home within an hour, never to return.

I suppose that I shouldn’t have been surprised to learn that affluent northern suburbanites could be as vicious as southern Klansmen. We later found out what we should have guessed: the people who chased us back into the District of Columbia had infiltrated the Fair Housing Association to prevent it from helping African Americans move into their neighborhoods. Viewing us as “block-busters” who would bring down home values, the infiltrators were prepared to do whatever it took to protect their golden eggs.