Stronghold

Nine candle holders made of soda-bottle caps glued on a piece of plywood. Paint and glitter and industrial scraps, bolts, nuts, pebbles, a whole mess of extra trimmings if you wanted. I did not. I only swamped the thing with glue, hoping it wouldn’t dry. When school let out the substitute sneaked up on me just past the gate, panting. “Oy va’avoy! Look what we almost forgot!” The glue had set, unfortunately. She made me take my Menorah.

I pressed it to my uniform skirt through the streets, a kindergarten project in the hands of a sixth-grader. Shameful, any idiot could see that, with a few exceptions. Such as Oreet. She held hers like a prize. She has about as much of a clue as the substitute, not that I’d say it to her face. Grades aren’t everything.

I smelled fried yeast dough and vanilla, Hanukkah. We found the source, a soldier waiting for a bus, setting off puffs of powdered sugar with each bite of sufgania. He smiled at Oreet with snow-white lips.

“You built that?”

“Me,” she said.

“No!”

“Yes.”

“You have an artist’s touch,” he said.

“It was an interesting assignment,” she said. “Take a kindergarten project. Bottle caps, wood, glue. Make a Menorah.

”Sure. I remember that,” he said.

“Then bring it up to date. See possibilities you didn’t then. Express your vision now.”

He asked her age. I had a better question.

“You back from the war?”

He said, “That’s privileged.”

“Not true. You can’t say where, exactly, or what you have seen, that’s all. You weren’t deployed? So you push papers. Or you’re maintenance. Supplies?”

He licked the powder from his lips. He eyed my work. “Yours came out rather shitty. That’s all right,” he said. “Not all of us can have the same abilities.”

I said, “You’re proof.”

Oreet caught up a few blocks down.

“Is he still after me?” I said.

“He never was. He made as if to. I apologized. I gave him my Menorah.”

Her hands were empty.

“Good,” I said. “That project was a waste of time and so is he. A perfect match.”

“You go too far,” she said. “I have respect for him. He is a soldier.”

“No. You want to see a soldier, see my brother,” I said, even if one thing my soldier brother isn’t so much, anymore, is seeable. He’s home now. He stays out of sight. Mostly he sleeps. He can’t forever. He’ll come out eventually. He’ll look the same.

“When will your brother be deployed again?” Oreet asked.

“That is privileged.”

We reached our grocers. There are two. Once we had one, now there’s a choice.

I said, “At last!”

“At last, what? You need something from the shop?”

“Only the trash.” I walked up to the dumpster. I commenced to stage a show, a horror show for my upstanding friend. I dangled my Menorah over green bread and flattened cartons, hopeless fruit, the reek of soured milk. “I don’t know what I’d even do with this,” I said. I let one finger lose its grip, and then the next. She almost died.

She snatched my work from me and kissed it.

“You just have to go too far. You’re crazy. It’s a Holy Implement. That would have been a sacrilege.”

“Keep it,” I said, “and enjoy. I have a real one back home.”

“So give it to someone in need,” she said. “Make a gift to the indigent”

“Aren’t you exemplary.”

“I just work hard.”

There’s no denying that. She’s our top student, first to study

for a test, first to complete it, first to volunteer when needed, first to offer her assistance to a failing girl, fairly impossible to shake, so far.

“Just for your information,” I said, “that kiss was idolatry, speaking of sacrilege. Don’t do it ever again in your life. Don’t ever kiss a menorah.”

“Where’s that idea from?”

“From my good brain,” I said. “Calm down. Yes, it’s a deadly sin, but you committed it misguidedly. Once is an error. There won’t be a twice.”

“You can’t explain.”

“I can. What’s this whole holiday about?”

“The triumph of the Maccabees. What are we, four years old?”

“Wrong. Cleaning house. Please pay attention to the name. Rededication of the House. We cleaned it out. We lit the light.”

“The House of God, the Light of God, in a Menorah,” she said, “which you should not throw in the trash.”

I sighed. “Not all of us can always understand, but that’s okay.” I took my project back. “So what you said. We’ll go with that.”

A crazy man named overalls lives in our town. I’ve never seen him dressed in overalls but that’s the name. It’s his name as our crazy man. He’s not our only one and not the worst, not the sort who must look for trouble, rage, get in your way. But he’s far-gone. He’s always in a rush, softly discussing agitating matters only with himself, unless he’s chased. I’ve never chased him, never has he noticed me, but he scares me the most. I see him the most. He’s my neighbor. He lives on my street.

Oreet knew just the house, knew the abandoned lot. She knows his name and knows it makes no sense, you’ll never see him wearing overalls. He wears the crazy clothes, layers upon layers in colors of mud and mildew and dust. She knows all that. She could believe that I know more. She does not live as close.

I said, “He has things he does this time of day. He won’t be there. We’ll never see him. He won’t see us. We’ll leave the Menorah and go.” I said, “Every soul in his family was lost in the Camps.” I heard that once.

“The highest virtue in giving is to give in secret,” she said.

“We should buy him candles,” I said. “Matches, too.”

“No, I should. You’re already giving your Menorah.”

“You gave yours, too.”

“That’s not the same. I want a part in this,” she said.

We faced the shops, two, very similar-looking, side by side.

“I buy at Peretz,” I said.

“Really? Peretz cheats.”

“You’re kidding.”

“It’s a well-established fact. I would have thought you knew.”

I did. But Alkalay’s throat is appointed with a medical device. “You want me to go in with you?” I said.

“There is no need.”

The buildings on my street, all of an equal height, were built by one developer, Egoz. The name is written on each building in mosaic letters, nice ceramic fragments recollecting ancient shards from digs. Each multistory is stucco-covered. Each stands upon pillars, shading parking spots, a small square lawn, flowering bushes, and a slide and sandbox for the children growing up inside. It is an ordinary street. One undeveloped lot is not unusual. Egoz didn’t build on it.

We passed my garden path and didn’t walk onto it. I felt my key under my blouse. I didn’t pull it out. I didn’t unlock our lobby door, didn’t press the button for the elevator, wait, or climb the stairs. We pushed through stalks high as our heads and stepped on dirt. It took no time to cross onto his land.

The world was wild and repetitious in there, like the sea, but golden, the parched gold of wicker, weeds and weeds. Deeper in, chalk, weeds paled to eggshell-white and suddenly malformed, blistered like underwater plants and as alive-seeming. They were alive. Snails had cemented themselves everywhere, from root to thorn.

“Nothing to worry about,” I said.

“Right.”

”Nothing at all. They’re the most harmless thing that you could see in your whole life.”

“The snails frighten you?”

“No! Why?”

She worked her lips and jaws. She spit. “Maybe I’ll wake one up.”

“You spit.”

“Sometimes that wakes them up.”

“You spit.I never saw you spit,” I said.

“Everyone spits.”

I turned around. I found the neighborhood still there. Sounds sifted through and I could see, in fractions, the familiar sights. Yaeer Bogana, building Nine, on his supposedly new bike, ready to let go of the handlebars—now!—as a lady on high heels clacked along, the type my mother says invests all of her brainpower in her looks. A lot of power, a complicated look. Even her walk was intricate. I undertook to know its parts. I staged a show for my fine friend. She almost choked. “You go too far.”

And she was right, this once. I overstated matters for effect, I felt invisible. But the reverse was true. Each move caused waves in the forsaken lot. One weed swayed thousands. Dormant snails seemed to come to rowdy life. Shells came in contact with our ankles and our wrists and necks too much. We dodged and tripped, and tripped again. The soil was weirdly rocky, planted with peculiar lumps.

A rusted skillet. At our feet we saw a kettle, too, a stockpot and a dented coffee boiler, pressure-cooker lid, colander, saucepan. We held hands like little girls, suddenly scared of pots and pans. Being man-made they seemed to have man-made ideas, and not good ones, or they wouldn’t be here. That couldn’t be true. I said uncultured people used this as their dump.

“For only kitchenware?”

We found slim loaf pans of assorted lengths and baking sheets, a Bundt cake mold—but also shreds of an old tire, a chair leg, one compacted shoe.

“Just normal junk,” she said. “You’re right.”

I let her hand go or she mine.

We raised our chins. We marched ahead. We nearly crashed into a wall. The weeds grew right up to the house, and we had been looking down.

The house, gouged, cracked and stained, was sound, made of materials from another time. The smell was foul but restrained. The boarded windows caged it. Just one window was exposed, showing its grimy pane. I placed my project on that sill.

I said, “It feels right at home.”

And she said, “You are doing a very, very beautiful thing.”

Crusted glue slanted all my bottle caps, each angled differently, the plywood naked, prettied only with my fingerprints.

“It fits right in,” I said.

She placed beside my Menorah the matches and the candles she had bought, the cartons spotless, labeled cheerfully.

She said, “Good, done.”

I pressed my face against the glass.

“Let’s go,” she said, but huddled next to me and squinted, saw what I saw and jumped back. A nest, layer on layer, in colors of mildew, mud and dust.

“That’s just his bed,” I said. I pushed the glass. A brown gum sealed it to the frame. “This doesn’t open,” I said. “This is not how he gets in. He’ll walk right by. He’ll miss it. All our work will be a waste.”

Our gifts collected, we crept on, circled the house, each window shuttered in a lasting way, door nailed shut.

We had almost come around entirely when we found his entryway. A curtain breathed, hung by two loops. The lace was filthy so the pattern was the sharpest I have seen. We stared in. Our eyes adjusted. We held hands again.

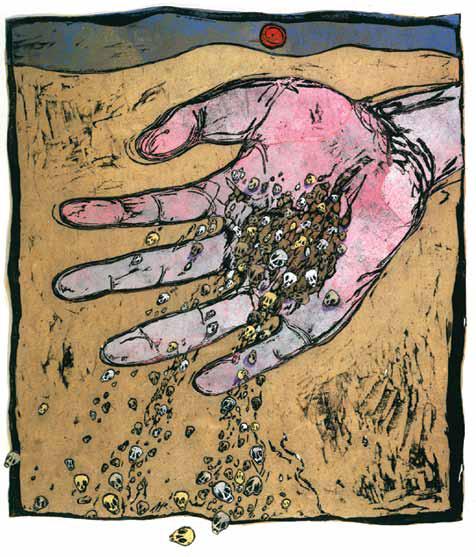

Like the Red Sea split, heaps of pots seemed to be flooding toward us in twin waves. They didn’t. They just reared up frozen. Everything was propped against two walls. A narrow corridor was left. It burrowed inward, maybe turned and twisted. That far in the dark we couldn’t see. We knew what was there. More.

Pots. Pots and pots, all stacked with terrible attention to each spout and mouth and leg and handle that could fix the project to itself. Overalls’ project. I had never seen him carrying a pot.

“Why does he do it?” Oreet said.

“How should I know?”

“They’re only pots,” she said. “Why should it be so dreadful here?”

“Oh, let me think. Is it the stench?”

She had been breathing through her mouth. She sniffed. The smell in fact was no worse than before. She leaned a little further in.

I grabbed her schoolbag, reined her by its straps. I said, “Use your own brain for once. It is a burglar alarm. Don’t even breathe on it, don’t touch. The whole thing will collapse. Think of the noise. Then what?”

“That’s right. You’re right,” she said. “You got it right.” She stared at me.

I heard the neighborhood, not far.

“But wait a minute,” Oreet said. “What sort of an alarm is that? If it is triggered while he’s gone, he’s got no place to sleep. If he is home, he’s trapped.”

“What do you want from me?” I said. “It isn’t my design.”

A cloud veiled and unveiled the light.

She took my Menorah and stood it on the sill. She stepped back to observe, chewed on her lips, seemed to be searching for the least upsetting words, like anyone was there who was upset. “Can we be sure,” she said, “that he’ll identify this as you meant?”

“Would anyone?” I said.

“I wasn’t putting down your work.”

“As if I care.”

“I wasn’t. I was picturing it from his point of view.”

She struck a match. She warmed the bases of ridged candles. She positioned them, held them upright. The wax set. She stepped back, observed, returning to rotate the candle box. The back faced forward now. The panel seen was the one printed with the blessings in their order, for such people who might not remember or know.

“Good, done.”

We left as we had entered, walking normally, just two girls in their usual way, simply more conscious of the ground under their feet.

Or so we meant to bring it to a close, that’s how we wanted it to go.

I left quite rashly and she after me, having no choice. The area of the whitened weeds seemed deeper than before. Maybe it wasn’t, as she said. Yet there they were and there they were, and I had had enough. We crashed through bone-white, fragile beadwork. Only snails, but they broke the heart, pitiable under our shoes, more sickening in their wholeness, in their bulbous repetition, in their fragile multitudes, each glued to all the others by the same secret command.

Under my building we leaned on my family car.

“We did good,” she said. “That’s what you should think about.”

At home toward sunset we prepared for the first light of Hanukkah, my sister and my mother in the kitchen, grating, frying, as my father pulled together our ritual supplies.

He coated the inner windowsill with foil against the drips. Next he collected each Menorah.

His and my brother’s were of silver. He removed them from the glass-front case. The girls’ were made of matter that when left exposed was not much changed. Mine waited all year upon a door frame and my sister’s with the potted plants. He brushed the dust off a brass lion, flicked a fly’s wing off a copper olive branch. He warmed the bases of ridged candles. He positioned them, held them upright. The wax set. He got matches ready and a prayer book. We all assembled. Not my brother. Last year he was absent, too. We lit without him. He was a soldier, there was war. There’s still a war, he’s still a soldier. He is home now. He stays out of sight. Mostly he sleeps. He can’t forever. Maybe he would come out tonight.

I knocked.

He said, “Go forth and tell thy father that his hymns are loathsome unto me.”

I went. I said he had a belly ache.

“Oy, and with all these heavy foods,” my mother said, as if he would have joined us at the table otherwise.

We lit, my father first, my sister when my brother should have gone, me last, our mother watching as the flames caught wick by wick. We sang the hymns, my father leading, starting with “These Candles,” and then all through “Maoz Tzoor,” the longest, each verse finding the same lesson in a chapter of our olden times. We won’t be extinguished. God is on our side.

I understand my brother is tired. I know he wants to sleep a lot. When he’s awake his manner is odd. It’s out of place. He goes too far.

I saved his meal, arranged a sample of each food, covered his plate, left out a fork and knife and spoon, a folded napkin, a filled cup. My sister rolled her eyes. Our parents praised me for my kind, constructive outlook. But I meant it as a dig. I am the one who knows he does not have a belly ache.

That night and every night of the eight nights I checked the view outside. I looked down on the undeveloped lot to find our influence.

It’s possible that our apartment has the wrong perspective, too much height above such small and short-lived flames. It’s also possible that Overalls didn’t use my Menorah. He never lit Oreet’s thin candles, didn’t sing a blessed word. Forget about her thoughtful setup. It was lost on him. He will not see parts as we mean them. He collects our household implements and gives them a new use, sees powers in them that we didn’t, and who wants to, right? Who cares. I will go only so far as to say I knew his place would be a mess. I knew that it would stink. As for his burglar alarm, there are simpler and better.

Naama Goldstein is an Israeli-American writer and translator living in Boston. Her collection of stories, The Place Will Comfort You, was published by Scribner.