So Much More to Sing: On the Death of a Woman Friend

When Elizabeth Swados died this winter, Rapoport was confronted with her insufficient ritual resources for mourning.

Left: Swados; Right: Rapoport.

In spring 1984, Ted Solotaroff invited me to La Mama, the downtown experimental theater in New York City, to see a performance by one of his authors.

Ted was an eminent editor, my first employer in publishing and an enduring friend. The author was Elizabeth Swados, directing “Jerusalem,” an oratorio she had composed to words in many languages — a signature of her work — and to Yehuda Amichai’s poems.

Amichai had been Liz’s guide in a walk along the walls of Jerusalem’s Old City, where she had been enchanted by the sounds of the quarters — Armenian, Christian, Muslim, and Jewish — all of which she incorporated into her own “Jerusalem.” Typically, she had also hired singers from these four backgrounds, bestowing a symbolic harmony on the semi-circle of performers as Ted and I sat before the open stage, waiting.

The singers waited, too. Out walked a slight woman with enormous hair. She stood before her singers, raised her arms, and then: That ravishing sound.

To my amazement, my eyes brimmed with tears. I had been a feminist since my teens. Jewish feminism had saved my Judaism and possibly my life. But I had never seen a woman do that: Walk out from the wings, inhabit the center of the stage, lift her arms, and elicit and conduct gorgeous music, written by her.

“Jerusalem” was mesmerizing — and Liz was its heart, leaning forward, coaxing and subduing the stunning, shifting sound. My dream as a writer was to retrieve the materials of the Jewish literary tradition for art, and here were the found syllables of the prophet Jeremiah and the poet Amichai unexpectedly in the East Village.

A few months later, Ted held a party in his apartment. When I came in, there was Liz. I would rather flee into the night than approach a famous person at a party, but I had to tell her what had happened to me at La Mama, what it felt like to see a woman whose image was mine — thin, huge hair — walk out and make that sound.

We began to talk. And we did not stop talking—through festivity and heartbreak, exaltation and despair — until January 5, 2016, when I stood before her hospital bed, dazed, as with two of her closest friends I chanted the Sh’ma and watched Liz leave the world.

While I write these words, I am listening to “Jerusalem.” I want to call Liz this second to say, “I never noticed that you used one of my favorite Ladino songs.” I want to tell her that one day after she died, I summoned on my laptop Maureen Nehedar’s Jewish-Farsi devotional poem, “Ashreichem,” and, alone in my apartment, wept as if I’d been cracked in two. I want to send her the YouTube video of three Jewish Israeli Yemenite sisters rapping in Arabic, which I know she’ll love.

She would love.

She would have loved.

But I will never talk to her again. Not in this world, anyway.

When I returned from a brief vacation to find Liz in the ICU, her devoted spouse met me and said without prelude, in response to my stunned, “What happened?”:

“She might die.”

The shock of that sentence is still in my body. Yes, she’d been ill, and in and out of the hospital in recent months. But the doctors had told her that recovery would be arduous and take a year. We were not nearly there.

I saw her on New Year’s Day, a Friday. I saw her on Monday, and my husband, Tobi, saw her Monday night. But when I came on Tuesday to rejoin the handful of friends in their loving vigil, the chasm of imminence was opening before us, pitiless.

Two hours later, I was texting our children, “She is gone.”

Liz was the children’s self-anointed goofmother. Which meant that every Hanukkah, no matter how many shows she was putting on, how many classes she was teaching, and how many books she was writing, a bag of eight customized presents arrived in our lobby for each child, until the age of college. Even in this last year, when I exonerated her because she was fragile, she would not relent, conscripting her friends — I found out afterward — to shop with her.

I found out afterward.

Afterward is when, as the great 20th-century philosopher Rav Yosef Soloveitchik piercingly observes, the full measure of the one you’ve lost assumes its magnitude.

Afterward is when, at the shiva and the memorial that followed, performers who loved her — of all colors, genders, ethnicities, accents, and geographies — came together to sing in her memory, men and women who had been homeless teens, Dominican young people, Jewish girls, African immigrants, NYU Tisch students, Latinas, gay men who had survived the AIDS epidemic, when Liz quietly fed homebound dying friends, actors who sang for her 40 years ago, and mentally ill young adults with their hard-won equilibrium.

Her intuitive kindness to the wary, to the wounded, did not temper the rigor of her art, but invited each one of those she auditioned and selected to give of themselves as completely as she did, to enter a world where what mattered was justice and beauty for the voiceless, for murdered nuns in El Salvador, for runaway street kids everywhere.

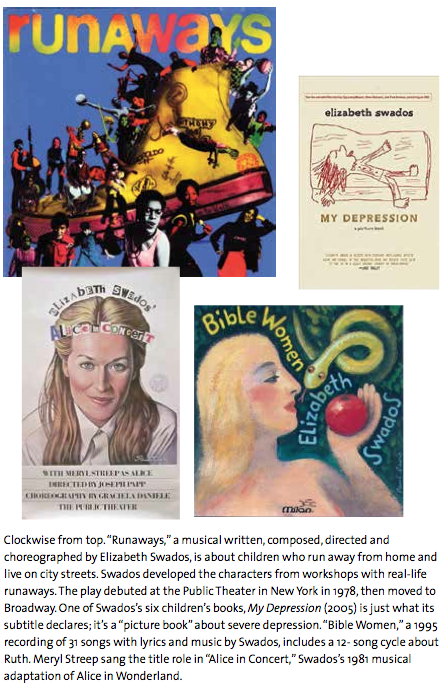

Liz directed, conducted, choreographed, wrote, and drew, but her heart’s idiom was music. Every form of music engaged her, and she mastered — and could be playful with — the most complex and sophisticated sounds from all over the world. She loved sound — birdsong, clicking, folk music; any culture on any continent was immediately accessible to her.

And I loved what I used to call “that thing you do.” The way she wrote a song that opened with a single voice, and then: The harmonies of a score of voices, layered one on another inseparably. I could not imagine what it was like to hear that multi-cadenced, transcendent sound first in her own head.

I wanted to follow her around for a day to find out how she could accomplish so much in the same time allotted to other mortals. I wanted to write a song cycle with her about women and aging, which she would set to music any time, she said. I tried to explain that, for me, from the thought to the deed could take a thousand years.

“I procrastinate, too,” she said brightly.

I was skeptical. “What’s the longest time you went from thinking you had to do something to doing it?” I asked her across the table at the café where we’d meet in the morning before both our days began.

She gave it some thought. “Three hours?”

Liz was in the flow. “I’m Liz Swados and I create,” said the homepage of her website, illustrated by her whimsical cartoon self-portrait. Abundance, the joy of making, was how she lived, through travails that would have crushed a lesser soul. Her life was unnaturally tragic — her mother a suicide; her brother a homeless schizophrenic who died on the streets of New York. But Liz taught me, when I sheepishly apologized for my own more minor troubles: “All pain is absolute.” And then she listened.

Our communion, as artists and friends for decades, was the music and texts of our people. She set Jewish texts to music and used Jewish languages in her work. Since she died, I hear in my head unceasingly her reggae Song of Songs, which she played with her singers and musicians as a gift to our family at our daughters’ naming and bat mitzvah ceremonies, just as she conducted “Jerusalem” at our son’s bar mitzvah.

We both had a passion for the Sephardi devotional music of piyut, the one gift of music I was able to bring to her, which shaped her score for “The Nomad,” inflecting the life of Sahara explorer Isabelle Eberhardt with Moroccan Jewish song.

I saw Liz’s production of “Job,” with clowns; “the Dybbuk”; “the Golem”; “Esther”; and, with my husband’s set designs, “Jonah” and the celestial “Song of Songs.” She had a plumb-true instinct for authenticity and, unlike many renowned contemporary artists who are Jews, never viewed her Jewishness as provincial, but as her unshakable identity and a source of infinite interpretive riches.

At each of our family celebrations, she concluded her performance with her gospel composition, “Holy, holy, holy/The whole earth is filled with His glory.”

Truly, in the words of the Psalmist that she also set to music, she sang to the Lord a new song.

When Liz died, I entered a fugue state in which I forgot everything. I staggered through the hours, offering the comfort I could to her mourners, desolate that there is no sanctioned Jewish way to grieve for the death of a woman friend.

Yes, Tobi and I did all we could for the shiva, but I needed a ritual, a ceremony that would honor the unique friendship between women, the dailiness of my leaving her messages on her answering machine:

“Elisheva! Lizzie! Lizzitude! Lizzardini! I love you.”

I wrote to Lilith to ask editors Susan Weidman Schneider and Naomi Danis if they had published such a ritual. I wrote to Lori Lefkowitz, scholar of women’s rites. They reminded me that I was the one who had written a book about grief for women. (Believe it or not, I forgot. I also forgot that the book includes a poem to Liz.)

It took a week, shiva’s tenure, for me to metabolize the fact that she was dead. That is, I knew it — Tobi and I kept repeating it to one another, preceded by the words “I can’t believe” — but I literally could not process it; my brain had a tripwire that continually returned me to before. I pleaded with her friends to explain why it had happened, as if medical clarity would…would what? Make her being gone comprehensible? Bring her back?

Liz is my fourth very close woman friend to die within one winter month. Lynda, Lisa, Mimi: The DNA of my shared life with each is now a helix of irreplaceable. I can’t decide if the rip in the fabric of the world that begins every November is better concentrated in a single month of yahrzeit candles—or whether mourning in intervals would be an improvement.

As if it’s up to us.

I believe in an afterlife where you see only the people you love. (And if they happen to love someone you don’t, you see only yours.) It’s not a heaven of angels in white, even if they are singing Liz’s music. It’s more like physics — or rather one of the few principles of physics I know. Energy never dies. The light of this kind of friendship cannot be extinguished; it must transmute form and be waiting for me some day when I, too, become non-material, everlasting.

Two Jewish girls from the provinces — she from Buffalo, I from Toronto — who met over music and poetry and New York City. Now she is stardust and I am bewildered, looping crazily between gone and glory, like the Hasidic aphorism of the person who walks through the world with a note in each pocket, one stating, “From dust you came and to dust you will return,” the other inscribed, “For you the world was created.”

So I ricochet through my days, unstable between the stripped-skin agony of loss without repair and the mystery that I was found worthy, for however long You chose, of this blessing.

Nessa Rapoport is the author of a novel, Preparing for Sabbath, a collection of her prose poems, A Woman’s Book of Grieving, and a memoir, House on the River: A Summer Journey. She is completing a novel. ©2016 by Nessa Rapoport.