Reconstructing the Life of a Labor Radical

Chances are high that you’ve never heard of labor organizer and American communist Elaine Black Yoneda. Biographer Rachel Schreiber probably wouldn’t have either if she hadn’t been drawn to old family photographs of Elaine that were hanging in the image gallery at San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum.

This relative obscurity attracted Schreiber, who approaches her new book, Elaine Black Yoneda: Jewish Immigration, Labor Activism, and Japanese American Exclusion and Incarceration, from the perspective of both a historian and an artist. As a photographer, Schreiber’s work focuses on portraiture. “It’s a way to make visible those who are often invisible in our society,” she says. So it’s not surpris- ing that in writing her first biography, Schreiber’s pen focuses on a woman who lived on the margins of society. When Schreiber was asked about the subject of this new book, she would answer, “I am writing a biography of someone you have never heard of.”

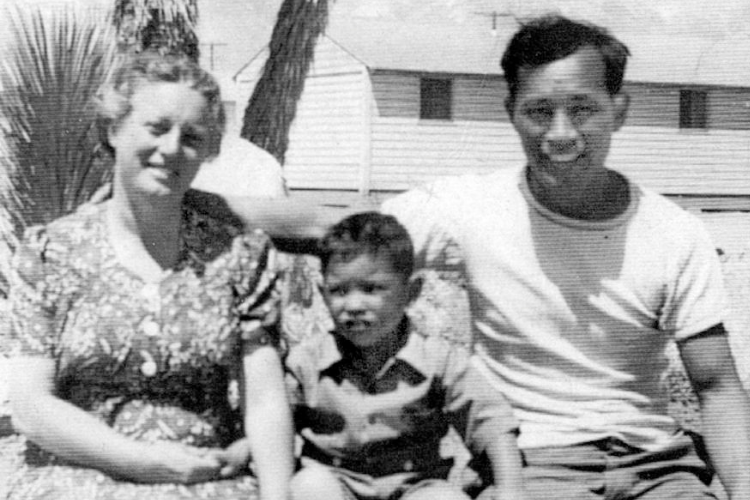

Elaine Black Yoneda, however, is more than a biographical snapshot of a Jewish American woman who lived from 1906-1988. Elaine was the daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants, as well as a divorced single working mother who later married a Japanese American man, Karl Yoneda. Elaine and Karl had a biracial son, Tommy, and the entire family was incarcerated at Manzanar War Relocation Center, a “concentration camp” located in between two small towns in California near Mount Whitney, during World War II. “The centerpiece of the book is their time at Manzanar,” says Schreiber. “They spent only eight months there and yet it occupies a huge place in the family story, and in the book.”

Schreiber’s choice of the words “concentration camp” and “incarceration” is more than intentional. According to Schreiber, Japanese internment camps were referred to as concentration camps prior to WWii. “I called them concentra- tion camps very deliberately as scholars uncovered a fascinating history. While incarceration was happening, [these sites] were referred to as concentration camps. After the Nazi camps were liberated, theU.S. went on a campaign to call them internment camps as they wanted to dif- ferentiate that history.”

Schreiber’s choice of the words “concentration camp” and “incarceration” is more than intentional. According to Schreiber, Japanese internment camps were referred to as concentration camps prior to WWii. “I called them concentra- tion camps very deliberately as scholars uncovered a fascinating history. While incarceration was happening, [these sites] were referred to as concentration camps. After the Nazi camps were liberated, theU.S. went on a campaign to call them internment camps as they wanted to dif- ferentiate that history.”

Schreiber also seeks to differentiate histories. Elaine’s family history in particular resonated with Schreiber who is also Jewish American. Her paternal grandmother went to Palestine and her maternal grandmother to Chicago. “They did not want to talk about the past, it was way too painful, as both were outside of Europe when the Holocaust unfolded,” she said.

They only learned of it through absence—the letters that stopped coming, the people who were not reachable… I think that does fuel my desire to tell these stories.”

Yet finding archival source materials of women during this period was difficult. As strong as her personality was, Elaine Black Yoneda was a rank-and-file labor activist and organizer for the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) on the West Coast at a time when gender discrimination limited women’s contributions to the workforce. “She was not famous, did not have a lot of privilege, and moved around a lot,” says Schreiber.

So Schreiber pored over archival photos to get a sense of the story behind the images. Two oral histories are central to her research. One was done for the Japanese Americans Project, Center for Oral and Public History at California State University, Fullerton—and the other one by the California Historical Society to document lives of California women. These oral histories provided audio accompaniment to the archival still photos that inspired the project.

Weaving these sources together, Schreiber is able to fashion Elaine’s story as a counternarrative to the history of Jewish labor activists, as well as women’s roles in the Communist Party. “Most of the history of Jewish labor activists is focused on the Northeast—mostly New York—and the Midwest,” explains Schreiber. “[These regions] were largely single racial groups. California was both multiethnic and multiracial…and while there has been writing about women in the Communist Party in the 1930s, it’s the same thing. I provide a view on the ground, the day-to-day of what it means to be a labor organizer.”

Schreiber allows us to follow Elaine in the local, everyday work of the International Labor Defense (iLd), which heavily involved helping workers who were targeted by law enforce- ment for their organizing: “bailing out arrested workers and raising money for the bail fund, visiting jailed workers and providing support to their families, and organizing protests and other events.” Again and again, Elaine puts herself at risk, sustaining blows, facing arrests and even standing on trial to defend her commitment to workers’ rights.

Her New York Times obit paid tribute to her chutzpah: “known in labor circles as ‘the Red Angel’ and as ‘Tiger Woman’ in the Hearst newspapers because of her militancy, she was the only woman on the steering committee of the 1934 San Francisco general strike.” Yet her fearsome status was mostly unknown outside those left-wing circles.

While her notoriety may have been limited in scope, Elaine Black Yoneda was ahead of her times in many ways. “She occupies double and seemingly contradictory spaces—Jewish, daughter of immigrants,” says Schreiber. “But relative to Japanese Americans, she is white. You can see in various moments in her labor organizing work and the way she dealt with being incarcerated, she was aware of the privilege she carried.”

As a couple, Karl and Elaine did share a common background as immigrant outsiders. But what Karl didn’t share with Elaine, according to Schreiber, is whiteness. And in this particular history, there are two parallel stories. “Elaine’s parents left Russia to escape antisemitism. Karl left Japan because he would have been conscripted into the Imperial Army. He was already a communist,” she says. “Both families, one from Russia, one from Japan—converge on the West Coast, both trying to get away from something and coalescing in a strange place in history, find themselves in a concentration camp.”

Elaine most likely could have avoided going to Manzanar with Karl. But one of the most surprising revelations for Schreiber is that Elaine and Karl did not oppose exclusion and incarceration. For a woman who spent her entire career standing up to authority and defending labor rights, Elaine didn’t fight to keep her son Tommy at home. Instead, she ended up volunteering to go to the camp as well.

Elaine most likely could have avoided going to Manzanar with Karl. But one of the most surprising revelations for Schreiber is that Elaine and Karl did not oppose exclusion and incarceration. For a woman who spent her entire career standing up to authority and defending labor rights, Elaine didn’t fight to keep her son Tommy at home. Instead, she ended up volunteering to go to the camp as well.

From April 1 to December 17, 1942 Elaine and Tommy made Manzanar their home. The Yonedas lived in shared bar- racks, in an open room measuring about twenty by twenty feet, sleeping on cots with army blankets made into makeshift mattresses. Trucks and cars would pass through the dusty camp without direc- tions or speed limits. Military-grade latrines were grouped together by gender, affording little privacy until Elaine lobbied the administration to build partitions.

But her activism seems to have been limited to these kinds of quality of life issues, “[This] is shocking to contem- poraries….I looked to see if they regretted [their decisions] later…,” explains Schreiber. “It was a very confusing time. There was chaos… to some extent, she just was doing in the moment what she thought was best for her family. “

For those of us who just lived through a pandemic trying to make life-or-death decisions day to day, this description may resonate. “As a historian, I try to get at the messiness,” says Schreiber. Fortunately for us and for Elaine Black Yoneda, Schreiber embraces the messiness of Elaine’s personal history and allows Elaine’s legacy to live on as a testament to both her perseverance and strength.

SooJi Min-Maranda believes in the power of personal stories and holds graduate degrees with concentrations in Korean American Studies and magazine publishing.