Reckoning with a Complicated Father

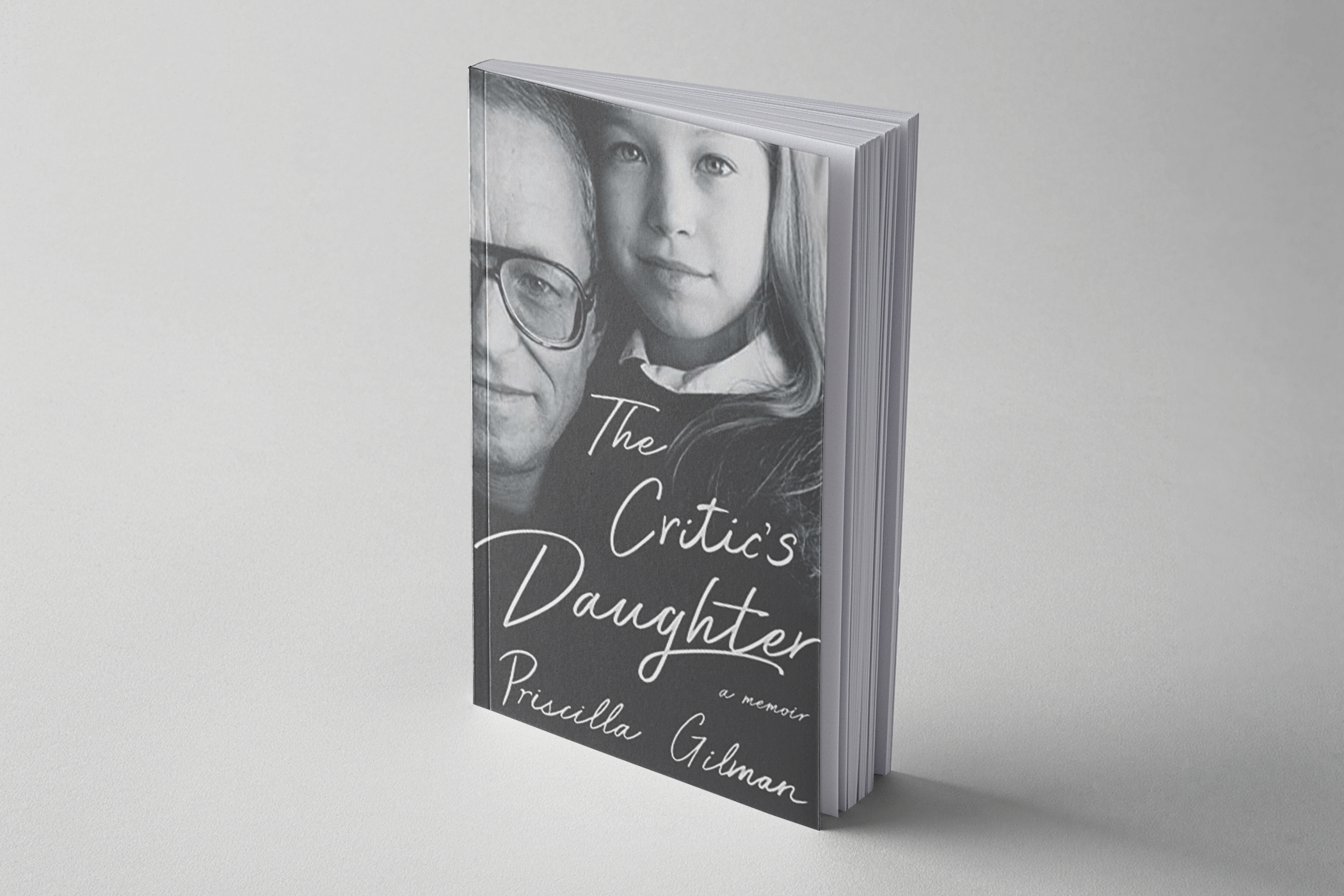

The 2006 death of prominent drama and literary critic Richard Gilman did not represent the first time his daughter, Priscilla Gilman, lost him. That would be when the author was ten, and her mother, power- house literary agent Lynn Nesbit, kicked out her philandering husband. Her parents’ separation, followed by years of acrimony, marked the end of Gilman’s childhood, and in The Critic’s Daughter (Norton, $25.00) Priscilla Gilman tries to come to terms with the loss of the father whom she revered.

“I am haunted by my father,” Gilman writes in her prologue. “He has made me the thinker, writer, parent, human that I am, brought me to my knees, led me into dangerous romantic entanglements, buoyed me during times of crisis, informed my reading and writing and parenting in ways I am only now realizing.” Until her parents split, Richard Gilman was the one who did most of the parenting, and, by his daughter’s account, excelled at it. “The priest of the cathedral space that was our childhood” Gilman writes of her father, then at the height of his cultural influence: theater critic for Newsweek, professor at the Yale School of Drama and a frequent guest on the Dick Cavett Show. But Richard Gilman is also irritable and exacting, prone to outbursts, and has the impossible standards you’d expect of one of America’s foremost critics.

The Critic’s Daughter hits home not just as an insider’s chronicle of a notable literary family, but as a depiction of the pain a broken marriage inflicts. Her father, devastated at being separated from his daughters, more than once tells them—they are ten and eleven—that if it weren’t for them, he’d kill himself. Meanwhile, Nesbit insists to Priscilla that her father didn’t really love her, but “he relied on you to bolster his self-image.” Nesbit also tells Priscilla that her father read pornographic magazines, had affairs— some with students—and that with Nesbit he was impotent. “You know what that means, right sweetheart?” Nesbit asks her ten-year-old daughter, and then warns her not to speak to her younger sister about these things.

Gilman tells us that neither she nor her sister were offered therapy until many years after the separation, and only after they insisted on it—remarkable, considering the Upper West Side psychotherapy- infused world her parents inhabited.

After her father’s death, Gilman asked her mother to put down in writing why she married him. Among the reasons Nesbit shares: she knew he would be a great father. “Basically he was a kind and ethical man.” Reading these words, Gilman broke down and sobbed. “I had been waiting almost 40 years for her to say these things.”

When I read this passage, which comes at the end of the book, I got the sense that Gilman wrote her memoir not just to explore her feelings for her father, but to redeem him, too. While some readers may have a difficult time going along with her, Gillman’s memoir is testament to an upbringing infused with a love of language and literature.

Alice Sparberg Alexiou’s most recent book is Devil’s Mile: The Rich, Gritty History of the Bowery.