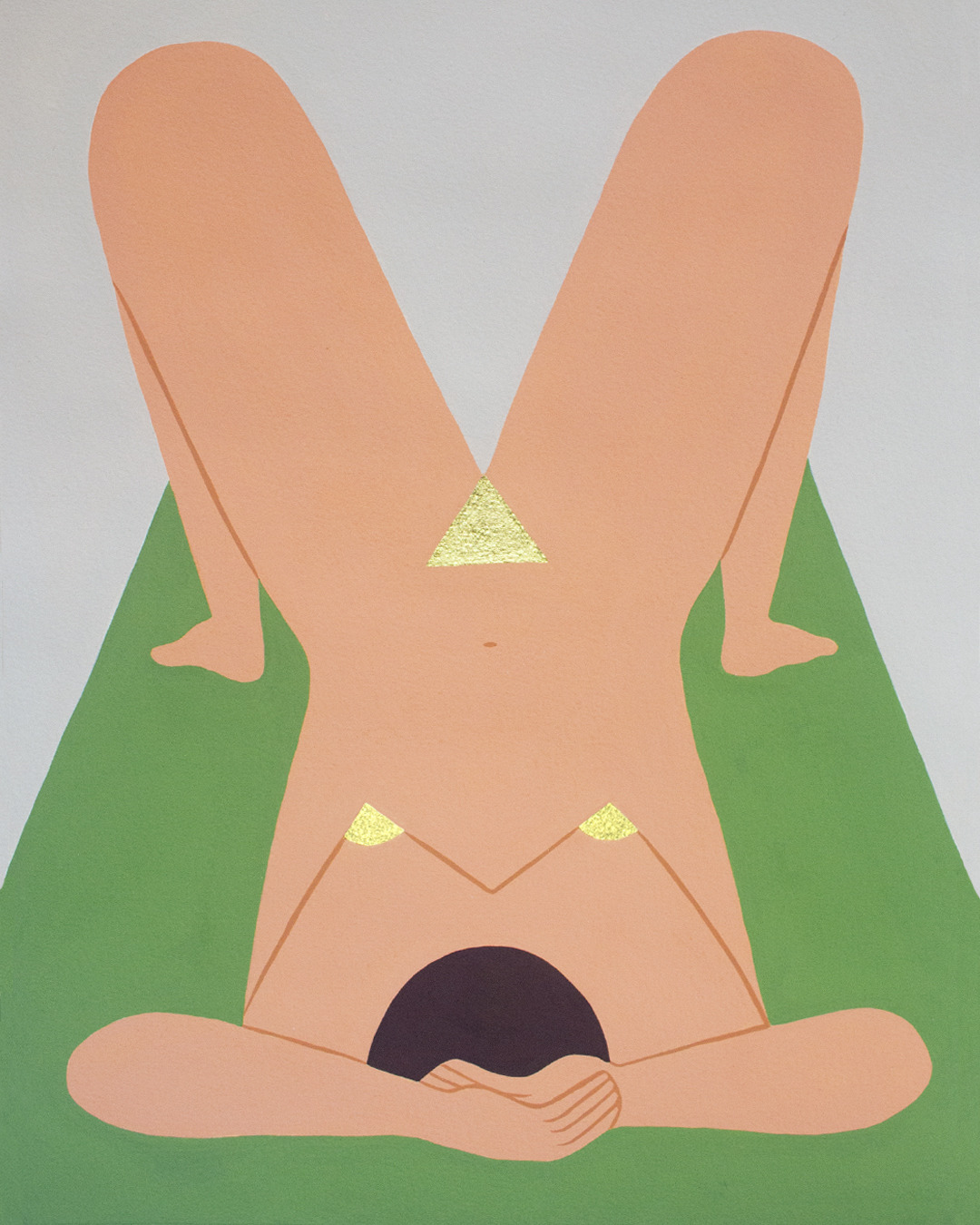

Art by Rachel Levit

Re-Doing Sex Ed

The first time I was penetrated I was 13. The rushed hand of an emergency room nurse—forceful, gloved, lube-less—reached inside of me to quickly check any cysts on my ovaries. The search proved unnecessary—I had appendicitis—and possibly caused my appendix to rupture.

I healed from the appendectomy but the trauma of the nurse’s hand, feeling as though she’d entered me up to her elbow, would join me at future doctor visits.

A few years later I sat on a paper covered exam table in a sea-themed room, waiting for my pediatrician. I’d booked an appointment under the guise of having a cold. But the issue wasn’t that I was sick, but that I was incredibly horny. And through my high school health curriculum, I’d learned the only way to not get pregnant was to be on hormonal birth control, and the only way to get hormonal birth control was through seeing a doctor.

The pediatrician entered the room. Convincing myself I was surely not the first person to ask her for a prescription for the pill, I nervously shared my request. The pediatrician looked at me over her glasses, her mouth forming a surprised ‘o’. She stumbled through a few questions which made me consider that perhaps I was the first person to ever ask her for contraception. “Have you spoken to your parents about this?” she asked me. “Yes,” I lied. I melted into the exam table, wishing I had just asked for cough medicine. Perhaps the pediatrician really was just used to babies and their booboos and I, oversized on the exam table, was just a huge, shameful slut. I left the office mortified, but with a script.

High school sexual education was a scary slideshow of STIs followed by a scary slideshow of various mugshots of “drug-addicts.” I remember the scabs on the meth users’ faces. I remember the health teacher explaining that STIs were infections, not diseases. But behind her, projected on the whiteboard, was a blown-up photograph of an oozing, herpes covered penis.

This January I stopped hormonal birth control after being on it for over ten years. No more pill, no more IUD. I’d decided, for the first time since learning about contraception, to question whether hormonal birth control was truly the only way to protect and care for myself. I was in part inspired to take reproductive education into my own hands after the irritating realization that my partner, a cis-man, seemed to know more about the names and locations of parts of my system than I did. My partner is no yoni expert, nor do I consider his knowledge—scientific, anatomical—to be more valuable than my personal, embodied knowing. What I realized was that his weird (and wonderful) Wikipedia brain had stored in it information that my mind had recoiled from, due to a mix of unwarranted shame and self-hatred.

Becoming a fifth grader was a big deal. We were bestowed the privilege of carrying three-ring binders we’d fill with math worksheets and pencil pouches. But the biggest deal was the start of the legendary Health Education curriculum. I’d heard about something called The Movie that the entire grade watched together. Its contents were a mystery, but rumor was we’d be shown some sort of cartoon penis. I’d heard whispers about Health Ed, a series of conversations we’d sit through following The Movie. For Health Ed we’d spend our elective period divided by sex, learning mystical secrets from our teachers. I couldn’t wait.

The girls sat in a classroom, blushing as our female teachers shared personal anecdotes with us. It was then that one of the teachers shared how, after giving birth, her nipples would begin to leak in the grocery store at the sound of the cries of a stranger’s child. Anything else I learned that week, including the contents of The Movie, immediately went out the door. All I remember is that image—my elderly teacher, chest soaked at Ralph’s, her body controlled by some insane, terrifying biological force. I looked down at my flat chest protectively. Whatever my future had in store, I was determined to outrule anything that could cause my yet-to-be bIoobs to leak in public.

I got my period for the first time when I was thirteen. It was a Friday and I was at my best friend’s house.

We’d walked home from school together, holding our backpack straps tightly and walking quickly because I’d desperately had to pee. Once in her bathroom, post long, glorious pee, I looked down at my underwear. The cotton was bright red and nearly soaked through. I immediately went into silent survival mode. Even though my best friend had already gotten her period and definitely had pads I could use, I wiped off my underwear as best I could, grabbed a handful of toilet paper, rolled it into a giant croissant-like pad, stuck it into my underwear, pulled my underwear up, and exited the bathroom as though nothing unusual had gone on.

I continued my silence when I got home, not telling my sisters or my mom. I replaced the wad of toilet paper with a pad my mom stocked for my sisters under our bathroom sink. Before throwing out the plastic pad wrapping, I wrapped it excessively in toilet paper, as though hiding any trace of my period could perhaps eliminate the reality of its arrival. I knew most of my friends had their periods, I knew my older sisters had their periods, but I felt as though I was in a blazing spotlight. I desperately wanted to avoid talking about “the changes” my body was going through.

Still, the next morning, feeling as though my mom would find out, I stated the news in the car. My mom was driving me to synagogue to attend a classmate’s bat mitzvah service. Her calm reaction made me wonder what I’d expected— why exactly I’d felt as though I was in trouble. As she drove, she talked about how wonderfully in-sync I was with the moon cycle, with the Jewish calendar. I looked out the window, relieved to not just have the secret off my chest but that my mom’s attention was directed at the moon and not at my body. I felt as though everything, everyone, was looking at my body. “It’s biblical!” she said.“Mazel tov!”

I learned about Pamela Samuelson’s class through a friend. I was sharing that I’d recently begun to transition off of hormonal birth control, and she enthusiastically insisted I reach out to Pamela. I was eager to have more support as I began practicing the fertility awareness method (FaM), and signed up to join Pamela’s Take Back the Speculum workshop. Through their Los Angeles-based practice, EmbodyWork, Pamela leads workshops and individual sessions in embodiment coaching and somatic education. Take Back the Speculum is offered multiple times a year, and rather than potentially limit its participants due to workshop cost, self-chosen donations are suggested instead of a set fee.

In the 1970s amidst the full swing of second-wave feminism, “reclaiming the speculum” trended through women’s circles. The speculum, and learning how to use it for self-examination, became a sym- bol of liberation and bodily-autonomy. Decades later, Pamela’s course is explicitly “open to & appropriate for all human beings with internal sexual anatomy”—a much needed correction to the oversights and subsequent harms of the second- wave. We were to be led by a teacher committed to honoring those who have felt unseen due to gender identity, race and/or queerness in “feminist spaces” in the past. Within minutes of the workshop beginning, I knew my friend had guided me towards an invaluable resource.

“I deal with adult people who come in with complex experiences about body shame,” Pamela shared with us, before guiding us through our own anatomy. “Feel free to put your hands in your pants while I’m explaining,” she said. I did, my fingers moving from pubis mons to clitoral hood. Pamela shared the better names for parts that “officially” hold male names (no more Bartholin’s Glands, Skene’s Glands, or the Grafenberg “G” Spot, and ANYTHING joyous instead of the pudenda, which translates to the part of shame), and encouraged us to Sharpie in the new names whenever we encountered a diagram—especially in medical school libraries.

I used a speculum, a tool I had squirmed away from on medical exam tables countless times before. Instead of waiting for the doctor to say the magic words of “all good, we’re done” as my legs shook and my body sweated, I lay on my back, calmly going at my own pace. For the first time, I got to see and not just briefly hear about my cervix. Pamela gave me the permission to, forever going forward, show up to any sort of gynecological or midwife visit with a speculum of my own. To take my time, and to tell them when I’m ready for the swab. To feel like the patient who is there to be cared for, rather than a meat slab, poked, prodded, then quickly sent away.

Years ago I received a voicemail from a gynecologist office informing me that my pap results were in, and I had HpV. I had one foot in the bathtub. I’d clicked play on the voicemail as the bath filled, expecting a message from a solicitor, not sensitive information about my body. I was recuperating from mononucleosis at my parents house and my capacity to deal with any additional health news was shot. I put my phone down, and got into the bath. The voicemail said not to worry but hadn’t shared what HpV was or if there was any protocol I had to follow. I looked at my red feet resting under the bath’s hot and cold knobs. I thought about the huge, nasty images of STIs that had been projected before me in high school. I I started laughing. I was truly a petri dish.

It turns out that around the time I got that voicemail, many of my friends received similar calls from

their doctors, sharing that they too had HpV. Some also felt incredibly confused—most of their doctors hadn’t gone into depth about what the virus is, when or how it would go away, and what the different strains of it are. The result of this brevity had led many of us to feel alone and ashamed.

In Take Back the Speculum, Pamela reframed what an experience with a health practitioner should be. I am not there for the convenience of the practitioner. I do not need to feel rushed as I place my feet in the stirrups, or to feel shame for calling back to ask for more information about my diagnosis. No one gets to tell me what to do. Our bodies, all perfect. Those of us who chose to participate in “The Gallery that Destroys All Shame” showed our bodies to each other, and let our classmates learn from our forms.

In an email to workshop participants, Pamela wrote, “Learn your own anatomy, your options around fertility and contraception, your resources for support for all outcomes. Take charge of this aspect of your life. Quit outsourcing authority over your body to other people whose licensure and conditioning has taught them to gatekeep rather than to educate and empower you, and whose capacity to first do no harm is being obstructed by things like trigger laws.” In a country that wants to regulate and disempower me, in a moment in which my ability to affect change feels devastatingly minimal, my new knowledge and my sharing of information with fellow vulva-having bodies is one part of my resistance.

Noa Kattler Kupetz is an educator and writer in Los Angeles and a former Lilith Intern.