Pri Chadash*

A strange, knobby thing, this new fruit. Leathery crimson skin bruised in spots, and a place like a rupture leading in deep, past the armor. Your knife severs it cleanly in two, slicing through red skin, thick white pith, and seeds that nestle in luminous rows like the most flamboyant Indian corn. You force your index finger along the edge of the broken skin, detaching seeds that snap as they are released into your palm, wrinkle your forehead apprehensively as you transfer a few into your mouth. Your fingers brush my hand as you give some to me, scarlet beads that glint in the harsh kitchen light like a glass of merlot, or like the Nile on that day when the Hebrew god turned the river to blood. They are smooth on my tongue and they burst when I bite down, spattering juice that is slightly sour, utterly foreign, just barely sweet.

There are other fruits on the table tonight: a bowl of apples, crisp and green, approaching a ripeness that wouldn’t have been fully achieved until the first frost. We picked them early, reaching up through the leaves, as the Mexican children do. It was we who were childlike; playing at harvest even as families made their migratory trek across the region, nomads with their lives in a pick-up truck, changing jobs and schools and doctors and markets and communities to put oranges, plums, cherries, apples on our table. We strolled through a pick-your-own orchard that day in the September twilight and you rubbed an oversized Empire on your shirt and raked your teeth through the green skin, reveling in the tang and the crunch. I sat shotgun in your car and our paper bag of apples was anchored between my calves, red-and-green shiny skins winking up at me as the light outside faded and the horizon glowed pink and gold. You stretched an arm toward me, handling the wheel easily, one-handed, with a competent softness, as the fingers on your outstretched arm twined between mine. The car hit a pothole, and we laughed as the apples leapt in their bag, settling back in with a rattle like gentle rain. Tonight we eat them sliced, browning slightly on their exposed white surfaces, dipped liberally in alfalfa honey from the farmer’s market that drips in luxuriant swirls onto our plates, between our fingers, until we are sticky with sweetness and the apples’ gentle crispness is drowned in a syrupy sweet that burns our throats. L’shana tova u’metuka: to a good and sweet new year.

A muddle, now, of fruit that is dried; there are raisins baked into challah, plumped to bursting in the eggy dough that is twisted into a round, fat braid. You come home in the evenings with a fresh challah, still warm, in a paper bag, that you bought at the bakery on your way back from work. You discard it on the couch with your corduroy blazer, like so much dirty laundry, as you join me in the kitchen, or in the living room, or in the bedroom. Later we emerge, giddy, you in my old hooded sweatshirt, and we discover the bag with immoderate glee, tear fistfuls off of the challah, and consume nearly the whole thing. Tiny raisins like buried treasure hide in amongst the dough, and their sparseness only increases their potency.

It is the harvest holiday, a time of ancient pilgrimage, and ironically, at this celebration of abundance, the fruit turns to paper. I cut apples and oranges and two-dimensional bunches of grapes out of construction paper, and we color them with markers, affix sequins with dabs of Elmer’s glue, string them from the ceiling of the sukkah, the ceremonial harvest shelter, with lengths of yarn. They flutter there, these flat, inedible fruits, dancing in the October wind that hurries through the gaping bamboo roof, swinging as far as their yarn stems will allow. You hold the etrog, the one real fruit of the holiday, under my nose, and I smell citrus: sharp, pungent, almost bitter. Etrog is an ugly word, you say. I agree, but the closest thing in English is “citron” and that is worse, false, like saying “skullcap” instead of kippah or “phylacteries” instead of tefillin. “Phylactery,” especially, sounds like some kind of prehistoric bird, with an enormous wingspan and a hoarse, lonely call. We lie in the sukkah at night, sharing a sleeping bag for warmth, and I run one of your curls between my first two fingers absently, possessively, and the stars sparkle quietly, muted by the sequins on construction paper grapes that are closer, easier to reach.

A pile of dried dates, of fresh figs, of carob-coated raisins and sliced oranges and olives with the pits still inside. The kitchen is crowded, with people as well as fruits: a woman pours carob candies into a metal bowl, and the sharp “ping!” when they land drowns out her earnest, openfaced laugh that sets her earrings swinging. A lanky man pours wine into the glasses on the table, set for far too many for it to hold; fills them to the brim until purple stains seep into the embroidered tablecloth. We gather, this curly-haired, wool-clad crowd, around the mountain of dates, figs, raisins, apricots, carob, prunes, oranges; we celebrate the fruits of trees that grow halfway around the world, in a place where snow does not tap at the kitchen window, collecting in drifts under the eves. We grin at each other from under lowered lashes, self-conscious now, praising a god who borei p’ri ha’etz, who creates the fruit of the tree. I consider the walnut tree in the yard, gnarled branches now coated with a layer of frozen snow, whose nuts we allow to drop in the fall, to be raided by squirrels, to rot. Reach for a succulent fig, flown in from South Africa, and take a bite.

“Oh, once there was a wicked, wicked man and Haman was his name, sir. He would have murdered all the Jews, though they were not to blame, sir.” What kind of propaganda is this, I ask you, irritable, brushing flour from my nose. We roll dough flat across a cutting board, cut round cookies from it, and fill them with jam: apricot, raspberry, prune. Fold them into triangles to represent the hat of Haman, this murderer of song and legend. How absurd would it be, I ask, if we made curly handlebar cookies and called them Hitler’s moustaches. If black people baked cookies shaped like the pointed noses of their white oppressors. If Native Americans munched on snacks shaped like cowboy hats. You shoot me a dirty look and tell me it’s just a children’s song. You have flour in your hair and a streak of prune jam, lekvar, on your cheek. Fruit that has been ripened past the brink of salvation, pulverized beyond recognition, preserved for far too long. The brown smear on your face twitches as you grit your teeth, bearing down on the rolling pin as the dough is stretched thin, too thin, and finally tears, creating a jagged hole in the center, irreparable.

The epitome of symbolism: a seder plate, decorated with scenes from the Israelite exodus from Egypt, filled with food that is much more symbol than sustenance. An egg, parsley, dry matzah, salt water. Bland foods, even unpleasant foods. An uncle lifts high the dish of grated horseradish, a dingy yellow; held aloft in improbable prominence above the gleaming flatware and bleach-white tablecloth. We pass the dish along with a bowl of the one fruit on the table: charoset, chopped apples mixed with nuts and wine and cinnamon, meant to remind us of the mortar used by Israelite slaves when they constructed the great pyramids in Egypt. A bite could be delicious: sweet red wine over tart apples, soft walnuts, a trace of spice. Before we can eat, though, we mix it with the horseradish, maror, a symbol of oppression. The fruit, by the time it reaches my lips, is tainted by a bitterness so intense that it makes my eyes water. I finish the little pile of bitter fruit on my plate. I avoid taking a gulp of wine to wash the taste away.

Hunger, too, is a part of ritual observance. To fast is to detach from the normal cycle of self-satisfaction, to think of things that are greater than the heavy feel of fullness in our bellies and sweetness on our tongues. It is hot; the July heat seeps through my skin, between the strands of my hair, around the edges of my eyelids. Eyes shut to the summer sun, I see red: destruction of the first and second great temples in Jerusalem, for which I am supposedly in mourning. I am in mourning. For lives and lifeways that no longer exist. For things that are irrevocably done: a temple comes crashing down, held together with nothing more permanent than mortar made from apples and wine, and no one can put it back together again. Like Humpty-Dumpty, I think, but I never liked children’s songs. A shadow falls across my closed eyelids and, unwilling to open them, I sense an Ancient Phylactery gliding above me, casting this shadow as its mammoth wings rise and fall, calling hoarsely as it slides over the sweltering horizon. Then there is an emptiness, and it is only later that, relieved, I can attribute it to my hunger.

I am chopping onions when the doorbell rings, tears streaming down my face as the onion essence burns my eyes. I wipe at my eyes impatiently, shoving the tears aside; I answer the door still holding the chopping knife. You offer me a pomegranate, balanced carefully on the palm of your competent, outstretched hand. You see my red eyes, the bits of onion still stuck to the knife I am holding. Take the knife from me, carefully slice the crimson fruit in two. You offer me a handful of seeds and I take them from your hand, where they rest in your cupped fingers like some coveted treasure. I close my still-stinging eyes and tilt back my head, pour the seeds onto my tongue, bite down. The seeds of the new fruit, thin skins yielding, burst in my mouth, more familiar than last year, and ten times as sweet.

Darya Mattes is a recent graduate of Cornell University. She now lives and works in Washington, DC.

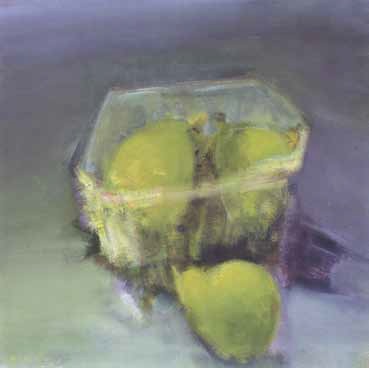

Painter Dina Toledano, born in Egypt, has lived and worked in Jerusalem since 1966.

*New Fruit