No Body Talk

Have you ever asked — or answered — the question “Do I look fat in this”? A Jewish summer camp makes “no body talk” part of its mission.

When Rachel Steinig first heard about the “No Body Talk” guidelines at Eden Village Camp, she found them “a little strange.”

When Rachel Steinig first heard about the “No Body Talk” guidelines at Eden Village Camp, she found them “a little strange.”

“I’d never encountered anything like this,” the 16-year-old says of that day five summers ago. When staffers performed silly skits on opening day to illustrate how life works at the Jewish overnight program, they included a bit about No Body Talk, which discourages comments about appearances — criticism or compliments — in order to get campers and staff to focus on people’s inner qualities.

At a time when everyone — from young children to teens and adults — is buffeted by heavily Photoshopped, idealized images of physical beauty, this camp’s zero-tolerance approach is decidedly countercultural.

Not complimenting someone about her skirt or refraining from a self-deprecating remark about what kind of hair day you’re having may seem like a small thing. But it’s a significant shift in orientation from the way most people communicate. And it creates a big impact, say people who have experienced this difference at Eden Village, part of what the organic farm-to-table Jewish overnight camp in Cold Spring, New York, calls “building a culture of kindness.”

“It has been highly impactful for both boys and girls, but typically the groups that have the hardest time with it and find it powerfully rewarding, even life changing, are the teenage girls,” reported camp director Yoni Stadlin in an interview.

Last summer Eden Village had 411 campers and 120 staffers. “They’re at the epicenter of societal pressure that is not being addressed in formal ways by schools and society. They are in this crucible. They’re being squeezed. They have the hardest time [integrating the idea] and the best time, usually, once they do,” he said.

Jenn Krueger was skeptical when she first heard about the No Body Talk guidelines. Now Krueger, 30, a rabbinical student who has been a “Tribe leader” — division head — for teens under age 15 and a tennis instructor at the camp, says “it took off all this pressure and enabled me to relax into myself in a way that made me feel like there’s this place in the world where there’s not so much social pressure. I felt like it was the first time in my whole life that the emphasis wasn’t on how I was looking and I could just be.”

To be sure, not everyone concerned about issues of teens and body image thinks that No Body Talk is the optimal approach.

“Girls and boys need the skills to deal with it. That’s what’s challenging to me about the idea. It makes sense that camp should be a place to give kids tools,” says Rabbi Tamara Cohen, director of innovation at Moving Traditions, an organization devoted to helping teens navigate the post-bar/bat mitzvah years in a Jewish way.

“Camp is an ideal setting to get the skills for how to talk about bodies and not make it a forbidden thing,” she says.

According to research compiled by Moving Traditions, 81 percent of ten-year-old girls are afraid of being fat. By middle school, 40 to 70 percent of girls are dissatisfied with two or more parts of their body, and “body satisfaction” hits rock bottom between the ages of 12 and 15.

Of American elementary school girls who read magazines, 69 percent say that the pictures influence their concept of the ideal body shape and 47 percent say the pictures make them want to lose weight.

“Ideally I’d want to see creating various spaces at camp for the conversations,” says Cohen. “In bunks, as a fun activity, maybe getting to hear from counselors or CITs how they’ve navigated some of the issues in their own lives.”

Moving Traditions has worked with a couple of camps about what messages people convey, intentionally and not, about body image and sexuality, and is expanding its program in conjunction with The Foundation for Jewish Camp.

In evaluating its program for post-bat mitzvah girls, Rosh Hodesh: It’s a Girl Thing!, Moving Traditions learned that “having a safe space to talk about issues of self esteem and body image and to learn to think critically about societal messages about gender makes a big difference in the lives of girls,” says Cohen.

Eden Village’s Krueger herself initially thought that No Body Talk might mean skirting difficult subjects.

“I was concerned it could be an avoidance of the issue rather than directly dealing with it. But what I found over time at camp is that it’s hard to understand it and the impact it has without being in an environment where it’s really carried out,” she says.

No Body Talk doesn’t mean no discussion, says Stadlin. On the contrary, the camp holds facilitated, deeper talks. “It’s just the off-the-cuff commentary we’re trying to mitigate. On the surface it seems like we’re sweeping it under the rug. But if anything we’re bringing attention to it.”

Each Saturday the camp holds “conversation circles” on a variety of different topics, from the fanciful to the serious. Older campers choose from groups devoted to “sacred questions,” “if I were president,” and body image. While most topics change each week, one always focuses on body image, Stadlin says. There are also other guided conversations about body image, particularly with teen and tween girls.

Without constant comments about appearance — or the anticipation of such — campers open up to deeper, richer conversations about body image and everything else, he says.

Personally, says Stadlin, abstaining from body talk “reduces mental noise in my own headspace, where I don’t have to think about comments about appearances. In this day and age, with the flood of stimuli and marketing and social everything, this turns the dial down and makes space for other things.”

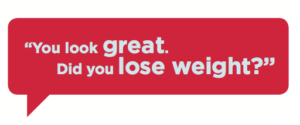

Eden Village has found that even compliments can have a larger, if subtle, negative impact, says Stadlin.

“There’s this feeling of ‘what is this person going to say tomorrow?’ It can cause a very slight hint of pressure after the good feeling washes away.”

“When I meet someone and he says ‘nice shirt’, to me, it feels good in the moment, and I’m not saying it’s a bad thing, but it doesn’t go very far and it doesn’t touch my heart,” he says. “When that’s off the table for the introduction, it pushes me to actually get to know the person better. That’s what I hope for the kids as well.”

Eden Village’s innovative approach can unleash a flood of emotion in campers who don’t even realize how much appearance-related pressure they had internalized.

“Within two or three days of being at camp teenage girls report it feels like it’s a huge backpack that’s been taken off them emotionally,” Stadlin says. “There are pain and tears about the effects and how they feel about it. For a lot of them it feels like the first time they can stick their head out of societal water. They can put their guard down and feel more free to be themselves.”

When Stadlin and his wife, Vivian Lehrer Stadlin, were developing the idea for Eden Village, he heard about the No Body Talk concept implemented in the Farm & Wilderness network of Quaker camps that has long employed the approach.

Before Eden Village first opened, in 2010, when initial staff was living on the campus, they tried it out. “It was challenging and very rewarding,” says Stadlin.

The camp integrated the approach right from its first summer. When staff introduced it to the first campers, “the girls were just bawling, sharing stories they’d never shared before about how much time they spent at the mirror and how bad it felt,” Stadlin told Lilith.

“This thing had been bottled up. Because nobody talks about this pressure that teens especially face. I sent the older female staff I had, who were more mature, and they made a talking circle” with the most-affected campers. “People shared hard life stories about how they felt about themselves with this pressure. Ultimately it was very healthy. Now a lot of those kids are on my staff.”

Tova Garr is a Manhattan-based life coach whose practice focuses on teen girls and their mothers. Garr previously worked in the teen department at New York’s Jewish Education Project, and she likes the No Body Talk concept.

“I love it because it comes within the context of education,” Garr tells Lilith. “It actually frees girls up, and boys for that matter. We see in boys’ world things we didn’t used to see, like eating disorders.”

And, says, Garr, “the value isn’t just the environment, it’s being able to notice what kind of internal conversation you’re having with yourself. How much of our day is spent thinking about what we look like? For many girls, that’s a huge part of their day.”

Being in an environment free of body talk “takes the pressure off,” says Garr. In her own time as a camper at a well-regarded, traditional Jewish camp, “every morning it was ‘what are you going to wear?’ I was the kid from Israel who didn’t have 5,000 fancy outfits. I spent most of the summer wearing other kids’ clothes. It was always a sense of being not good enough, not being able to measure up. It is so much a part of camp life, this comparing. The guideline takes a huge load off,” Garr says. “That frees you up to see who you really are.”

She spent a day at Eden Village one recent summer. “The day I was there was a drum circle. The kids around the circle didn’t look like kids at other summer camps. I’ve visited hundreds of camps. You always see girls very put together, wearing makeup. Here most of the girls were not made up. They looked like they were hanging out in their own home without anybody watching.”

“Kids here make clothes,” Stadlin says, “and instead of a compliment you can say ‘What’s the story with that hat?’ and then someone can say ‘My grandma taught me how to crochet’ and now we’re talking about grand traditions, rather than that token good feeling you get for three or four seconds.”

Jeremy Fingerman, CEO of the Foundation for Jewish Camp, tells Lilith, “to us it’s very impressive…I think of No Body Talk as creating a safe, sacred space for kids and staff.”

While Fingerman isn’t aware of other camps using the same approach, he said, an increasing number are focusing on anti-bullying efforts and increasing their focus on chesed, kindness.

Still, No Body Talk wouldn’t work at every camp. Isaac Mamaysky runs Camp Zeke, a two-year-old Jewish camp in the Pocono Mountains focused on physical health and wellness.

“We have a lot of campers coming to us because they want to become fitter, want to think about the condition of their bodies, saying ‘I’m going to leave faster, stronger, with bigger muscles’. Our t-shirts say ‘fitter, faster, stronger’. It doesn’t mean people are focused on appearance all the time,” said Mamaysky. But it does involve discussion of how people look. “We have a supportive culture where body talk is part of it because we’re working on the bodies,” he said.

The Camp Ramah system of nine Conservative-movement residential camps doesn’t have a policy in place like the No Body Talk guidelines, but “We do a lot of training before and after camp about how to reduce social and sexual pressure at camp,” says Rabbi Mitchell Cohen, executive director of the National Ramah Commission. “It has been one of our top topics.”

“Such a high percentage of difficulties in our camps come from problems in these areas where kids’ self esteem is based on body image, how they feel about kids picking on them, the whole bullying thing. There is a lot of education about not talking negatively about other people and not emphasizing outward appearance,” says Cohen.

Similarly at the Reform movement’s Camp Eisner, which has over 900 campers over a summer at its campus in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, there is no single policy in place.

“For me, it’s not just about No Body Talk. It’s how do we give campers skills within the world that they live in? How do we show them that it’s really possible to live in a way and care for one another in a way that doesn’t change the entire environment?” says Louis Bordman, Eisner’s director. “We’re able to do this at Eisner because we have the microcosm of society, they all come together and we teach them skills and ways of living and being Jewish so that they are able to see what b’tzelem elohim [in the image of God] really means. It is an entire approach.”

Back at Eden Village, Rachel Steinig liked the sound of the No Body Talk approach when she first heard it, but was “a little worried about its execution.”

“I thought it was going to be really hard but it turned out a lot easier than I expected,” says Steinig, a home-schooled 11th-grader, who lives with her family in the Mount Airy section of Philadelphia.

“It definitely felt like a relief. I’d finally come to a place where people would like and value me for who I really was, not just my body. In our society there are a lot of pressures on women and girls to look a certain way. All of those pressures disappeared when I came to camp.”

After her first summer, when she was 12, she came home and tore up her back issues of Teen Vogue magazine, she said.

“I’m really grateful I came to camp around middle school, and high school is when wearing the right clothes and getting boys to like you is a focus,” says Steinig, who attended public school for 9th and 10th grades. “I was really well-equipped to handle these kinds of pressures. I’m not as affected by negative or positive talk about appearances anymore…. I’m not as quick to judge people. Of course I still do, we’re all still human, but I don’t jump to as quick conclusions.”

She brought the approach home, and her family has integrated it too.

“Occasionally we do talk about body positivity but try to refrain from saying things like ‘Oh I look so fat in this outfit’,” she says. “We’re not totally super-strict. We go by what we think is kind and loving. Different things work for different people. As long as there’s a kind and loving intention behind it, it’s fine.”

Debra Nussbaum Cohen is New York correspondent for Haaretz. She has written for The New York Times, Wall Street Journal and New York Observer and authored Celebrating Your New Jewish Daughter: Creating Jewish Ways to Welcome Baby Girls into the Covenant. Her daughters have been Eden Village Campers; she has also done grant writing for the camp.