#MeToo in High School

I vividly recall the school-wide assembly my high school held to discuss date rape. Our friendly and peppy presenters reminded us that sex with a too-drunk-to-consent person was against the law even if both parties were inebriated, whereupon dozens of male students, in the throes of a tidal wave of shock, got up to decry the unfairness of it all—the brutal cruelty to men.

That day in about 2000 came back to me this winter when I read an essay by an 11th-grader named Abigail Fisher in her (Jewish) high school newspaper, describing the way her classroom conversation recently devolved after a discussion about #MeToo. “I worry that because my male classmates could more easily imagine being falsely accused of rape, they were more empathetic towards the perpetrators than towards the victims,” she wrote. “They were thus unreceptive to the female voices in the room who spoke strongly, though some on the verge of tears, about their feelings and fears surrounding the unstoppable wave of sexual assault allegations.”

Outraged teenage boys. Tearful teen-age girls. It’s all too familiar.

Today, there is an alarming national trend of abstinence-only sex education (which tends to position women as gate-keepers and men as aggressors). In the last decade, the federal government has invested over $1.5 billion dollars into abstinence-only education, despite statistics that show it to be ineffective.

These kinds of messes can still happen even at the schools that supposedly care about sex ed. And that’s partly because messages about consent—whether they come from porn, pop culture, or parents—are imbued early and often. “High school is too late to start talking about consent,” says Jaclyn Friedman, sex educator, activist and author of Unscrewed: Women, Sex, Power, and How to Stop Letting the System Screw Us All. “If you’re getting resistance at that age, it’s because it feels like a shift in everything kids have learned from the culture up until now.”

In secondary education, where the gendered power imbalance and prevalence of disturbing (and often hetero-normative) social hierarchies may be even worse than in the “real” world, it can be hard to fight the tide and instill new values: affirmative consent, for instance, in which an enthusiastic signal of “yes” is required, rather than the absences of a “no.” Yet there is hope, say a handful of Jewish educators and national experts. There are models that work, and that are worth trying. But they caution that a true emphasis on consent can’t be checked off in a single class period, or a day. There are no tips and tricks, no “magic bullets” says Debra L. Hauser, president of the youth sexual health organization Advocates for Youth. Instead, it requires a commitment from every level of education, starting with lessons from the earliest age about not touching others’ bodies or things without an OK—along with emotional education about love, healthy relationships and respect.

“It starts in kindergarten when a kid grabs something from someone and a teacher says ‘you have to ask permission’,” says Hauser. “So by the time you get to puberty education you’ve laid the foundation of how you ask for consent.” Starting early also lays the groundwork in another crucial way. “If language (around sexuality) is introduced early, it is less ‘magical’ and taboo,” says Kate Greenfield of Rodeph Sholom School, a K–8 day school in New York. It’s the same principle behind teaching toddlers to name their body parts with correct anatomical terms rather than slang; the goal is demystification.

I emailed a healthy assortment of Jewish schools to ask how they approach this topic, and only a few got back to me—but those that did respond were eager to share their approach to the curriculum. Consent-based sex ed can and should be done Jewishly, they say. For instance, before students at Solomon Schechter Westchester start sex ed, they read a passage from the Talmud in which a student hides under his teacher’s bed while the teacher is having sex with his wife. When his teacher discovers him, the student explains his action thus: “This is also Torah [that is, how you treat your wife in bed] and I need to learn it.”

“One of the lessons here is that the teacher should have taught this!” says Rabbi Harry Pell, the Associate Head of School for Jewish Life and Learning. “Also, the piece makes it clear that while the student’s presence is inappropriate, what’s going on is mutually consensual. And that the bedrock principle [of sex] is understanding and consent.”

At Schechter Westchester, a K–12 school, “We’ve been talking about consent for years,” according to Sami Mazo, the school’s 11th grade dean and 10th grade health teacher. “It’s the staple of our health education. We talk about consent, and we do so explicitly. We talk about what it means in non-sexual situations, and we talk about what it means to have a healthy relationship.”

Rabbi Pell points out that whether they’re Jewish or not, schools that have a point person or a unifying curriculum through the years have a major advantage in being able to teach consent effectively. And everyone I spoke to suggested that if schools are willing or able to commit to peer education and teacher education programs, they’re in a much better spot.

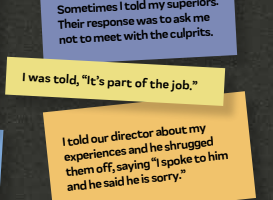

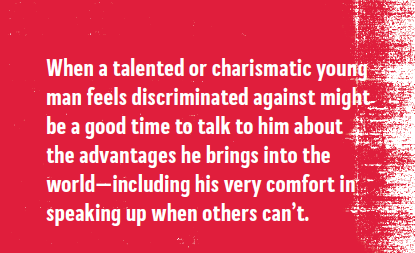

At Jewish Community High School of the Bay in San Francisco, Roni Ben-David is that point person, serving as the Director of Social Justice & Inclusion. She works with teachers to provide the solid grounding they need when tough moments crop up. “I’ve been working with faculty and staff,” says Ben-David. “We’re talking about how to turn uncomfortable moments—which are happening more and more… into those teachable moments.” At Schechter, the staff tell me that the moment when a talented or charismatic young man feels discriminated against might be a good time to back up and talk to him about the advantages he brings into the world—including his very comfort in speaking up when others can’t.

Yet before those moments happen, a lot of that work must be done outside the classroom, Ben David notes. “When I’m reacting to something I see in the news, I have to process and learn with my colleagues, and do some of my own emotional work too, so I don’t get in their way. So in preparation to talk about #MeToo, for instance, I’ve been reading lots of articles and listening to interviews online.” Experts emphasize that it can be difficult without real institutional support and training for teachers, who have their own blind spots or discomforts, or even traumatic personal histories, to venture into the territory of #MeToo on a random Tuesday when a kid wants to talk about Aziz Ansari or Harvey Weinstein. And that puts schools burdened by budget issues or controlled by a top-down hierarchy (like a religious denomination, potentially) at a disadvantage. “Planned Parenthood and other organizations do trainings for people who teach sex ed,” says Jaclyn Friedman, author of Unscrewed. “But who’s going to pay for that? As a teacher, do you have to do it during your time off? Part of the reason sex ed is such a mess is not just about prudery,” she notes, but about red tape and budgetary priorities.

The impact teachers have, beyond the health classroom or special assembly, can be lifelong. I recall watching videos about consent and harassment in my 10th grade health class at the end of the last millennium—dated videos in which women with big permed hair and shoulder pads, relics of another sartorial era, contended with all the same issues we’re now talking about as #MeToo continues to roil the world.

Yet my first #MeToo conversation was the very same year, at which point any lessons about consent and respectful sexual environments our school had attempted to deliver had been obliterated by a social world where sexual rumors were printed in the school paper, boys dominated every extracurricular activity, and homecoming parties offered an opportunity for older boys to prey on drunk freshmen teen girls (who themselves would have been outraged if you called them victims).

To be honest, I don’t really remember drawing any clear line between the staged discussions we had in class and the nascent horrors that were beginning to crop up all around me. It actually took a faculty member to explain to my friends and me that some of what we were describing was, in fact, sexual harassment—that the term didn’t apply just to the besuited businesswoman in a popular legal advertisement shouting at her boss, “This is sexual harassment… and I don’t have to take it!” a line that was treated as a big joke. We were amazed that it could actually apply to us.

That’s why any discussion of consent has to go into deeper issues of power and control, and maybe interrogate the social hierarchy of high school itself, including issues like race, class and gender. “You have to ask, ‘What does power do? How does power cause people to get what they want? How does power silence people?’” asks Sami Mazo, of Schechter Westchester. “When you start to hear that one person or one opinion dominating the room, you have to shut it down and unpack it. I’ve had kids push back many times, but we want to develop an atmosphere where we’re teaching kids to have empathy for each other.”

Debra Hauser of Advocates for Youth notes that that instilling that kind of empathy means addressing students’ needs on all areas of the gender and privilege spectrum. “Because the world is imperfect, we still need to educate girls to stand up for themselves, and we still need to focus on educating boys about respect and consent,” she says. “The pie is big enough for us to do both—while remembering that LGBT kids are more likely to experience dating violence. So for all kids, the idea of communicating boundaries, wants and desires go hand and hand.”

By starting with the younger members of society, schools actually have a huge role to play. Because as most of us know, there’s never going to be a real sea-change unless something fundamentally shifts in society. As that high school student wrote, after her classroom erupted in misogyny: “We can write until our hands are bloody, speak until our voices are hoarse, but unless our school, our community, and our country decide to believe women who come forward, my friends and I might have to say ‘me too’.

Sarah Seltzer is a writer and editor in NYC. She tweets at @sarahmseltzer.