In The Beginning There Was This: Fat

And then I started cutting

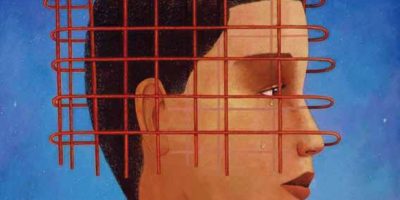

“Behold,” my arms cry. “My bourgeois pain!” “Hark, my narcissism!” The bloody gashes weep with melodramatic intensity, drawn by an angst-ridden author, stroked into being by a sure artist’s hand. My arms are like a Jackson Pollock painting, I say. Seemingly random, the marks have been applied with painstaking precision. Pollock applied his paint not with broad swaths, but careful drips. I apply mine with a steady grip and the most precise of tools. Pollock worked with a brooding intensity, unable to see beyond the task at hand. I work feverishly, too, mind numb to everything but the blades and the blood. His palette was never particularly varied and neither is mine. Shades of purple, echoes of white, salmon. red.

In actuality, my scars have begun to fade. Their theatrical power is being eaten away by hungry flesh, by greedy time.

I was such a good girl. Really I was. Good grades, good behavior. Good hygiene.

Until fifteen, anyway. At which point I stopped eating. I dropped my fork with a clatter and, with my other hand, I picked up the razor. In the beginning, there was this: fat. The three-letter word that seemed to encompass everything that was wrong. Not just my thighs or my stomach, but my soul. I was ugly and fat and stupid and worthless. All day long the words rattled around my brain, lodging in the nooks and crannies and taking up residence there.

I was never much good at starving. Never thin enough or hungry enough or dizzy enough. I was, I thought, half-assing it. Just like everything else: epic fail. This was a source of great shame. I couldn’t even starve myself properly. Eighty eight pounds was thin, maybe, but it wasn’t success. Not by a long shot. Later, though, I found something I was good at: cutting. And, for a time, that was enough.

I was sixteen the day I first cut myself, and I’d gone out with friends. I’d ordered salad and pushed it around with my fork, willing myself not to eat the croutons. Or so I recall. Maybe that is something I’ve remembered wrongly. I remember going to the movies. Coming home. Picking up the razor from its place on top of the shower. Carving away at my arm. Beads of blood. Getting caught.

Explaining myself required some fast thinking and fancy footwork. But I did it. It was easy to lie to my mother. I was doing it for her own protection.

But these are just details. Accessories. The real story was somewhere else. Beneath my skin.

What I really remember is this: that each slice of the skin, each jab at the arm, felt like nothing so much as a caress.

It didn’t hurt. Not really. And even if it did, I deserved it. That’s what I felt. Who was I to complain? To hurt? There were, I knew, people out there with Real Problems. It killed me to be so self-centered.

Soon I would discover that the Bic razor, with which I’d started cutting, was too clunky, too big a brush to paint my masterpieces. And it didn’t give me rivers of burgundy flowing from lily-white wrists, showy expressions of my despair, elegant declarations of sorrow, physical manifestation of the war brewing in my adolescent brain. And so I graduated to single blades, purchased in packs of ten. I bought them at the drugstore with issues of Vogue. I began on my stomach but quickly moved on to bigger and better canvases. The scars became deeper and redder, inching out from my torso to my upper arms and ending halfway past the elbow. I consumed countless tissue boxes in my quest for mental health. And-oh-so-many yards of medical tape. I stained many sets of sheets. A brand-new comforter.

No, the cutting didn’t hurt. Not really. It was everything else, every other moment, that stung.

There are people starving in Africa.

My mother used to say that when I was small and wouldn’t finish my dinner.

There are people starving in Africa.

Starving Africans, I felt certain, would see me for what I really was: a narcissist of the highest order. Someone with incomprehensible luxuries: to self-starve, to self-mutilate, to self-loathe. To mortify, like a good Catholic saint. But I was just a nice Jewish girl. A nice Jewish girl faking it.

What I wanted was to be entirely selfless. Without need. To give and give and never complain.

If I cut, I could contain everything. Then no one would ever know that I was someone plagued with selfish thoughts. That I was weak in this way. I could run the razor across my arm and feel so much better. Like I’d articulated everything without uttering a word. Like I’d gotten what I deserved.

I could run the razor across my arm and then get on with the business of Being Good. I could run the razor across my arm and then get up and study for my U.S. History A.P.. I could smile and laugh and play the role expected of me. I could say nothing and hurt no one and I could be perfect. Or, at any rate, I could seem perfect.

I wasn’t perfect, though. In fact, I was a sinner. Because it turned out that Jewish law prohibits self-injury. The verse is Deuteronomy 14:1 — “Ye are the children of the Lord your God: ye shall not cut yourselves, for thou art a holy people unto the Lord thy God, and the Lord hath chosen thee to be His own treasure out of all peoples that are upon the face of the earth.” A teacher at Gratz Hebrew High School had told me that. In a class on Jewish law. He went on to speculate about the motivations of those sorts of people. Cutters, that is. I didn’t hear him because my heart was beating too fast and the din in my head was reaching new volumes. The conclusion was unassailable, though: God hates me, too.

But if I was a bad Jew, I was still a good woman. A perfect specimen of femininity.

Anorexia, cutting — these are overwhelmingly female diseases. Women are supposed to be self-sacrificing, to swallow our needs, to bury our anger. Self-harm is what happens when these “feminine” traits are taken to their extremes. Self-injury felt like an understandable response to a world in which women are perceived as weak for having feelings, trivial and selfish if we so much as have needs. The psychopathology of a self-injurer stems, at least in part, from the requirements of the cultural construction of femininity.

We female cutters are merely doing too well what all women are expected to do very well.

I told my mother, finally, during an argument. Summer was coming and I couldn’t wear long sleeves all the time. My hometown in Delaware is hot and sticky in the summer, humidity driving heat indices ever upward.

So, in a characteristically idiotic fashion, I hurled the cutting at her, aiming to wound. Maximizing the moment’s dramatic potential, I rolled up my sleeve and thrust my arm in her face. “You-didn’t-even-know-about-this,” I said. You didn’t even know about this. I regretted it as soon as I said it.

I couldn’t take it back, though. Just like I couldn’t take back the red and white and pink graffiti that now colored my arms, legs, and stomach.

Cutting lost me forever my place as the good kid. I was dethroned. Summarily dismissed. Pushed off from atop my pedestal. Good Kid became Damaged Goods. Anorexia was a blip. A painful, troublesome blip, but a blip nonetheless. No permanent damage. No real harm done. Cutting, though, that was different.

My mother set about trying to erase my scars. We went to the dermatologist. Multiple times. There were, it turned out, no easy fixes. We investigated plastic surgery and lasers, debated the effectiveness of various topical gels. My mother set about trying to erase my scars because even more for her than for me, they hurt. She saw the scars as her failure, her failure to notice. She could barely look at me. We were bound by love and guilt and hurt for what we’d done and what we hadn’t. For the things we said and the things we couldn’t.

And then there was this: she didn’t want me to go to college. At Vassar, she wouldn’t be able to keep her eye on me. She couldn’t ensure I’d be safe, she said. She worried that, good student that I was, I’d strive for better marks in self-destruction. That one day, with hard work, I’d get an A. An A for mission Accomplished. For potential Actualized. She said, “I couldn’t live with myself if something happened to you.” It seemed best not to mention that most of my injuries had occurred under her roof. That something had already happened to me.

That spring, Mrs. Bowersox, the mother of a retarded child I mentored as a volunteer, caught me unawares, my sweater off, as I was parking my car. I didn’t know anyone was around. I thought I was safe. She never liked me after that. “It’s not,” she told me sternly, “a good thing.” The word “cutting” was not said, but we both knew what she meant. She let me play with her daughter that afternoon, but she didn’t like it. Didn’t like me. Mostly, she didn’t like IT — that elephant in the room. Afterwards, she almost always found a reason to cancel.

Freshman year at college there was the blood-bank employee who wouldn’t draw my blood. Too much scar tissue around the veins or something. “People do the craziest things,” she noted. I nodded.

The summer I was twenty, a portly cashier at the Au Bon Pain on the corner of 15th Street and Fifth Avenue, in Manhattan, told me I was crazy. “They ought to send you to Bellevue,” he said good-naturedly. I smiled, embarrassed. What did one say to that? How did one begin to defend oneself against the not-sobaseless charge? He gave my friend and me free cookies.

There were cab drivers, passersby, countless numbers of salespeople. They all said the same thing: What happened to your arms? Nasty cat, I would remark. Or, accident with a weedwacker. Track marks from my years of living on the edge. Most often I said nothing. Just shrugged, adding, “I’m fine.” And then, “Don’t worry about me.”

I’ll admit it: Mrs. Bowersox made me weep. She was the first. But soon enough I toughened up. My mom, though. What I did to her will never stop hurting.

Jay was the first boy to see me naked. I took his hand and said, Here, let me give you the tour. I ran his hand over my stomach. This is where I started, I said. You see, I thought I was fat and it seemed only natural to attack what ailed me. I guided his fingers over the raised scars that inched up to my belly button. Then I put them on my arms. And this is where I went when I ran out of space and I still couldn’t fix myself. Sometimes, I told him earnestly, it’s just too hard to be.

Jay counted my scars. “103,” he said. “When I see you again, I don’t want there to be any more. You need to find a way ‘to be’ that doesn’t include razors or Band-Aids or blood.”

But I didn’t see him again. He saw me naked and he stopped calling. He stopped calling and I pretended not to care.

My co-workers never knew about me. About my scars, I mean.

In the summer, I’d stop a few blocks from the office and cover myself up with a sweater. I’d spend all day in the non-airconditioned loft, sweating.

Brian thought I was religious. That my long sleeves were evidence not of madness, but of piety. Never mind my short skirts.

I told him the truth because he asked and because I thought he could handle it.

“Can I see?”

I hesitated.

“Sure,” I said, rolling up my sleeve.

“Jesus!” he said. “Jesus Christ!”

“It’s okay,” I told him. “Really it is.” And then, after a minute, “After you’ve known me for a while, you won’t even see them.”

That was a lie, of course. Because my friends never stopped “seeing” them. But because it’s a subject of which we never speak, I can pretend they do.

It’s always strangers, I’ve found, who ask the questions. The people you love — the people you are dying to give answers to — they ignore the scars altogether. Out of politeness, maybe. Or because they just don’t really want to know.

“I was a teenage cutter,” the headlines would say. But that’s only part of the story. Rather, I was a teenage mess. I was aching and wounded and the razors only made that manifest. And I wasn’t the only girl to feel this way. Studies posit that seven million American women suffer from eating disorders, that one in every two hundred adolescent girls self-harms. And these, of course, are only reported cases. We can only guess at the number of women and girls suffering in silence. If these figures pertained to men and boys, would the world be more attentive? I feel sure that it would.

Feminist theorist Susan Bordo writes about women’s struggles: “Loss of mobility, loss of voice, inability to leave the home, feeding others while starving oneself, taking up space, whittling down the space one’s body takes up — all have symbolic meaning, all have political meaning under the varying rules governing the historical construction of gender.” And more than that, cutting and burning and hungering and puking — these are obsessions that distract us from our power, that sideline us from protesting our oppression, from chipping away at patriarchy. They are politically useless. Self-injury is a trap. It keeps the construction of femininity intact and women silent. It keeps our indictment of society unheard. It changes nothing.

But for me, nevertheless, it felt like self-injury worked. But only for a minute. It calmed my brain-hammering thoughts, muffled my excruciating feelings. They always came back, though.

And when they did, all I had was a bloody arm.

In the end, age twenty four, I’ve kept my scars. Despite Mom’s pleadings. This makes life complicated.

None of my extended family knows about this. My grandparents — Bubbie and Zaidy and Gramma and Poppy — should never, must never, know. They don’t need more tzoris, and besides, the past is the past, right?

Which is to say that my grandparents haven’t seen me in short sleeves in years.

Which is to say that I have an extensive collection of cardigans.

Which is to say that nothing is perfect.

I’m more than the sum of my scars. Of course I am. Selfinjury doesn’t define me. But my scars are part of me. They’re ugly, but they’re honest, too.

Kathryn Harrison wrote, “Scars are stories, history written on the body.”

And here I am now, waiting to be read.

Marni Grossman graduated from Vassar College with a degree in Women’s Studies. She has written for BUST, Playgirl, Heeb, Sadie Magazine and gURL.com. You can find her online at thenervousbreakdown.com.