Her Jewish Roots Grow in Prison Soil

I wasn’t expecting the email from Chaplain Scott when it arrived in my inbox one Tuesday morning in November of 2011. “Dear Rabbi Rice, Would you be willing to correspond with a Jewish inmate seeking spiritual guidance and counsel?”

I knew my response: I had no time, of course. I barely managed to respond to my congregants’ needs. And yet, when I hit ‘reply’ to send my decline, I found myself accepting the request instead.

Linda Whitaker wrote to me two weeks later. Or rather, I received my first letter from Linda two weeks later. She likely wrote it sooner, but since the U.S. Postal Service is the only means we have by which to communicate — Linda has no Internet and only highly restricted and expensive phone access — the ancient art of letter writing became our dance.

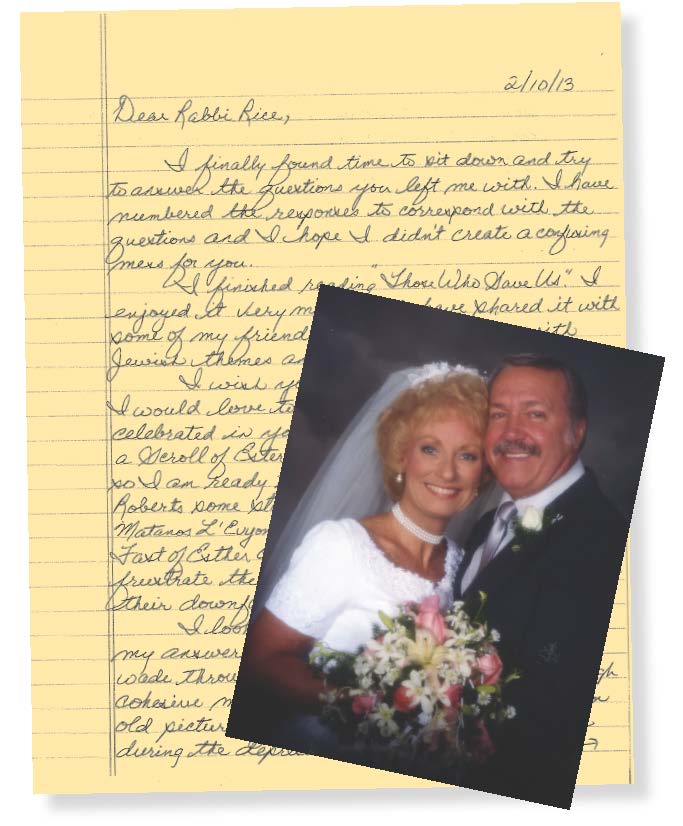

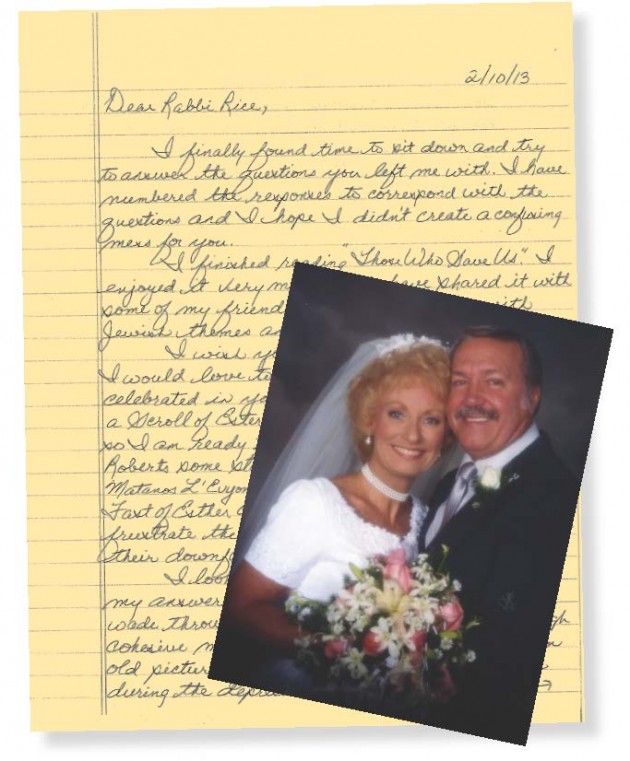

One of the letters Linda Whitaker sent to Rabbi Laurie Rice this winter. Linda and James Whitaker (her 4th husband) on their wedding day, in August 2000.

At first she was serving her sentence at the maximum security Women’s Penitentiary in Nashville, where she was just one of two Jewish inmates. In her current location, at the State Women’s Prison in Memphis, she is the only Jewish inmate. Over the next year and a half, Linda and I would write back and forth. I would do my best to send her what she needed in the way of Jewish books, study materials, and ritual items. She wanted a tallit, so I sent her one of mine.

Linda was 52 when she was convicted and charged with the first degree murder of her husband. The law in Tennessee requires that Linda serve a minimum of 85% of her sentence, 21½ years. That means she’ll be in her early 70s before she is considered for release. She will have spent her 50s and 60s living in a world that most of us can barely fathom, save for what we glean from TV shows and movies.

I caught a glimpse of Linda’s prison universe from the inside when I visited her this past January. It was the day after her 60th birthday, on a very cold and gray morning. I drove up to the women’s prison and passed through the many cell doors that serve to separate inmates from the outer world. I had carefully planned what clothes I would wear: simple, old, colorless. Somewhat like the exterior of the prison itself, which was dull and brownish-gray on the outside, nothing green or colorful growing anywhere. The prison exterior looked to me as I might imagine the nuclear reactor at Chernobyl — stark and lifeless.

I entered the front door carrying only my handbag and a brown paper grocery bag full of books that I had brought for Linda. Like her, most inmates own little or nothing. Each can keep in her cell only what she can fit into a six-cubic-foot drawer under her bunk. And most inmates, including Linda, share the cell with a roommate, so privacy does not exist for yourself or your belongings. You’re simply lucky to coexist peacefully with your assigned roommate.

The prison provides only the bare necessities for each inmate: food, bedding, and basic clothes. Many inmates take jobs on the inside to earn money. Linda works with the education program so she has a desk and “office space” which grants her extra room to keep her things, like the books I send and the other Jewish materials she receives from Aleph and Chabad. This job that Linda works at most days pays practically nothing, a few dollars a day at most. But those dollars are sacred for Linda; they afford her simple purchases through the prison store, everyday items that many of us on the outside take for granted, such as shoes or toiletries.

After registering with the security officer by the front door and sending my bags through a scanner, I was instructed to walk through four cell doors down a long hallway. The smell of lunch from the prison common room grew stronger as I made this long trek. I would not be meeting Linda in the visitation room. I would be entering the heart of the prison, where most visitors never walk. Our visit was special, as it had been arranged by the chaplain. I found myself standing in the main artery of the prison. There were no prisoners visible — they were being counted, their final count after lunch. I stood there for what felt like an eternity before one of the many guards noticed me and pointed me to the chapel.

The chaplain greeted me and arranged a table for Linda and me to sit and visit. When we first met in person, in the middle of the prison chapel, we embraced and took a moment to simply see each other after so many letters back and forth. And then we began to talk. We spoke about Linda’s Judaism, her background, the support she has received from Jewish organizations while incarcerated. I have learned that most liberal rabbis are not eager to visit inmates, that this is mostly the work of Chabad and the Orthodox. I do not judge. It took me a full decade after receiving my ordination before I chose to reach out into the prison world. I think we rabbis have a great deal of fear surrounding what such a connection means for us. I know that when I went to visit Linda, I was both nervous and intrigued about what it would be like to enter the prison.

Linda and I talked about how she arrived at the place she is today, a Jewish woman destined to serve over 20 years behind bars. We spoke about the challenge of maintaining one’s humanity, much less one’s Judaism, within the confines of prison. She then wrote out by hand her thoughts in response to some of my questions.

Rabbi Laurie Rice: Linda, tell me about your family background and what your life was like prior to your incarceration. How did you come to live in Tennessee? And how did you come to be incarcerated? What happened?

Linda Whitaker: My bubbe, Dora Glinski, was born in Romania and my zeide, Samuel Josephs, was born in Russia. I don’t know what year/years they came to America, and I don’t know if they met here or in Europe before immigrating. My mother, Sarah, was born in this country in 1924 and I was born here in 1953. My father was not Jewish and my mother always played down the fact that she was Jewish. As a result, I was not raised in a religious home, even though I was raised in an ethnically Jewish neighborhood in Queens, NY. I regret that when I was younger I didn’t ask my grandmother for details about her life in Romania and her experiences coming to America. My grandfather abandoned Dora and her four children during the depression, so I never met him. My grandmother was a very strong woman who struggled alone to keep her family intact during hard economic times and without her husband present to help. Sadly, when my grandmother was in her 80’s, she had to be placed in a nursing home. Another patient with mental illness problems wandered into her room one evening and bludgeoned her to death with her bedside lamp. When my uncle sued the nursing home, he was awarded $1 for my grandmother’s life. The judge told him that was all she was worth because she was no longer capable of generating income. Samuel was never heard from again after he abandoned Dora and the children. They were living in upstate New York at the time and Dora had to place my mother and her siblings in an orphanage while she returned to New York City and set up a place for the children to come to. Eventually, Dora got all four of her children back under the same roof. She never re-married that I know of.