Half Moon Grill

PLATES OF UNEATEN FOOD from the dorm kitchen are piling up around me in my room. My boyfriend, who lives down the hall, keeps bringing me new plates on his way to class, and, when he gets back, he takes away some of the old ones. There is something wrong with every type of food in the world and it has not yet occurred to me that the thing they all have in common is my own palate.

My young body is so tired. I am taking a political science class about the American Dream that, had I taken it a year ago, would probably have changed the trajectory of my academic career, but it is the Winter quarter of my senior year and I am grown up enough to accept that I am three classes away from an English major. I love this class because every chapter of every book reminds me of my grandfather, but I can barely complete an assignment. Even the thought of sitting at the computer lulls me into uneasy sleep.

To pass this class, to be the first person in my family to go away to college and come back with a degree, I have to get an A on the final exam. To get the A, I have to stay awake. The morning of the final, I buy a gigantic box of chocolate-covered espresso beans and set it down on the table in front of me. I write a longhand extemporaneous essay about my grandfather’s American dream and am walking out of the room in two hours flat. Once again, I have pulled a rabbit out of a hat, but I feel no sense of victory. Despite the hundreds of milligrams of caffeine coursing through my body I am so tired, so bafflingly tired, that I ride a shuttle into town and buy a pregnancy test.

I take a pregnancy test.

I take another one.

Somewhere between the drugstore and the unisex dorm bathroom off the computer lab I have crossed into an imaginary country, a flat dusty place with a crossroads and nothing else as far as the eye can see.

In the mythology of the blues, the backbone of the music I know best, a crossroads is an ancient place. It’s a dangerous place, where choices are made that can never be undone. You can lose your soul here; you might not get out at all. It’s not a place for dithering. I am so tired, and I need someone to come and take me by the hand and tell me how to get out of here. I need old wisdom, but my grandmothers are dead.

I think my grandmothers stood here, once, twenty years apart. They chose differently, in 1946 and 1966. Martha’s path ended when she died of cancer at sixty-five, the center of the family she loved and raised.

Enola’s path ended at thirty-five, the heart suddenly cut right out of the family she was loving and raising. I know how, but the why will never make sense.

It had been a rough road since the first Western wave of the Great Migration, but Black San Francisco, in the sum- mer of 1965, was a vibrant place. The Southern immigrants had moved out of the overcrowded tenements of the war years and were working on the first generation of San-Francisco-born children; the Fillmore and Bayview neighborhoods were the eastern and western poles of Black life and culture. On Friday and Saturday nights, men and women shed the anonymity of their workday uniforms for the glamor of trim hats and sharp suits, high heels and furs.

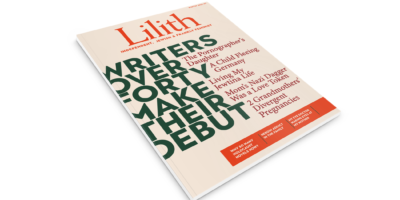

The Western Addition neighborhood, just east of the Fillmore, was where Mrs. Bettie Lewis kept a restaurant called the Half Moon Grill. She was one of the Ingram Sisters, the most glamorous of the Friday night crowd, once the most sought- after debutantes in Pine Bluff, Arkansas before boarding a bus to San Francisco in the company of their niece, Martha.

The Ingram sisters had strutted into the Fillmore, back in 1945, and more or less never looked back on that provincial little city or the baggage they’d dragged with them in the shape of seventeen-year- old Martha. One day Martha came home from school and her gorgeous aunts were in the wind. She married her boyfriend and stayed married to that difficult and wonderful man forever.

Martha was my grandmother, and every bit the most respectable housewife anyone knew from the time she was a girl of eighteen with a baby son on either hip, radiating unconditional love and the dignity of a privately-held sadness. Her sadness came out in music, in Aretha’s songs of all-consuming, world- leveling love. She played Aretha’s first single—”Never Loved A Man” backed by “Do Right Woman”— on lonely Saturday nights, flipping the 45 over and over long after the children had gone to bed.

I feel the need to say that Martha had dignity and she was loved and respected, because when Black women get respect, we help one another hold it. Our respect is fragile and utterly conditional, and a single choice can carry it away forever.

And here I am, poking at it. Here I am, digging up a story Martha kept for the rest of her life and folding it into my own. I’m turning the story of her problem into my own word problem. But I’m not sure the math on that hasty teenaged marriage works, and I need her story to help me make sense of mine.

I need to know if she will stand with me at that haunted crossroads. I need someone to tell me what to do. Here’s what I think: I think she thought about her boyfriend, whom she loved, and who loved her. I know he said he would marry her, which covered a whole lot of unarticulated promises. I think that she looked at herself in the mirror, this seventeen- year-old who just wanted to be the first woman in her line to graduate from high school. It had seemed possible when she stepped off that bus from Pine Bluff. And now, here she was, just a girl with a choice.

But did she have a choice? Was it really a crossroads for her, or just one lonely path stretching out ahead? Did any friend whisper in her ear about a woman who could come to the boardinghouse late one night and solve that word problem? I’d guess she knew something about that— her aunts were sophisticated women of the world—but I don’t know if she would have known how to make it happen even if she wanted it to.

After all, it was Bettie who, five years later—when Martha was 23 and already a mother of 4-, 3-, 2-, and 1-year-old boys— marched her over to Planned Parenthood down on Oak Street and got her the means to stop at the fourth stairstep.

Whether or not Martha chose at 17, she certainly chose at 23.

This might have been the act that redeemed Bettie for abandoning Martha, because Martha’s family wandered comfortably in and out of the kitchen of the Half Moon Grill, lifting recipes. I have made her gumbo recipe; that, at least, she passed down. She would go over to the Fillmore, to Alvarado Fish Market, and pick out the feistiest Dungeness crabs and fresh-smelling shrimp and gumbo file. She would go out to the Bayview to get the fatty sausage that enriched the soup base. And when she did that, though she might not have known it, she was crossing paths with my grandmother Enola, the one who was a stranger to me my whole life.

Enola is the grandmother who didn’t raise me, Martha’s equal and opposite. Her absence was deafening. A conversation could take certain turns that put me face-to-face with that absence. The only thing I could do, then, was turn around and run back to something familiar: the one-sided conversation between a child of divorce and the non-custodial parent she sees when the timing works out, the setting is in neutral territory, and her parents are speaking to one another. (The frequency was like a Fibonacci sequence: each visit is farther apart from the one before, and it seems random until you are old enough to understand where the trend is headed.)

Martha wore Avon Skin So Soft hand cream that came in a rainbow of jars and smelled like tuberoses and lilies. Her favorite color was lilac, and I heard her last word. My children were raised on the living memory of her warm arms, and her love of learning, and Aretha’s voice asserting “a woman’s only human” before an uncaring man and the world that belongs to him. I can even taste Bettie’s food, made in my own kitchen. I don’t know Enola. I can’t sing her songs. And I don’t know if I am entitled to fold her story into my story when there are living people still tormented by the violence of her absence and the utter silence that came after.

Because Enola, too, was respected and loved, that I do know. The silence was a wall, built up to preserve the respect the people in her life had for her. The silence was doing the work she started when, in 1966, she made a choice that was supposed to give her back her own destiny. She, too, had ridden out of the South after a young lifetime of Sundays spent in the churches of New Orleans. She was a respectable married lady, and she was trying to stay that way.

At the time, Enola was in love with David, a married man who ran one of the places Black San Franciscans were dressing up to go to. She was married, too, but had been separated from her husband for a while, and was raising her children largely on her own for the moment. She was very, very beautiful—that’s the one detail that still transcends the silence, after all these years. And, at the start of the summer of 1966, she found herself pregnant, and standing at a lonely cross- roads of her own.

David told Enola he would leave his wife. For a while, she believed him, because she wanted this baby, wanted it enough to feel comfortable telling people about it. But somewhere between concep- tion and June of 1966, Enola changed her mind. Some people say that she had decided to reconcile with her husband and stop waiting for David to leave his wife.

Here’s Enola’s word problem. She had and was supporting two children. Her husband, their father, was a steady provider who cared about her. Enola grew up in the church. Occam’s Razor says that Enola decided to leave a volatile, uncertain situation and return to the stable one, to claw back the respect that David was never going to give her. It’s the most comfortable answer, especially so because we treat it as if it explains what came next. She wanted to go back to her husband, and so she made her choice. This time, the choice was to try to have an abortion.

(It has taken me this long to use the word “abortion.” I noticed, too.)

The fact that I am uncomfortable using the word, and that I feel I have to imagine Enola’s reasons, bothers me. I feel that I have to justify her choice. At a time when her choice to have an abortion carries the significant risk of death, my instinct is to explain that for her to make that choice she had to have felt she was in a dire situation. And yet I don’t know if that is the judgment she made. Maybe she decided she wasn’t up to raising three children. Why do I want her to have a practical or altruistic reason? There is an awful prejudice around women’s reasons for abortions, and Black women’s reasons more than any. Even though I think that prejudice is appalling, is it my place to put Enola in front of it, even almost sixty years later? Is it my place to keep poking at my foremothers’ secrets and exposing them to the criticism they dreaded?

But I’m selfish. I want Enola at the crossroads with me, even if she can’t be.

I want her to help me make this decision. But I can’t have her, because, at the age of 21, still a couple years out from my next Fibonacci dinner with my father, all I know is that Martha got married and lived, while Enola had an abortion and died. By no definition of the word can I say that she had a happy ending.

One night, Enola was carried out of her house past her terrified young children, leaving a bed drenched in blood to haunt their nightmares. There was a woman at the club who did abortions—rumor has it that it was David’s wife. I’d like to believe that woman tried her best but perforated something, probably the intestine. I dug up Enola’s death certificate; it says that she died of sepsis, that catch-all term for dead women of childbearing age that any student of women’s history can decode. And, just like that, Enola was erased, because if we couldn’t talk about her death, we couldn’t seem to talk about her life, either.

What would it be like to have a grandmother on either side of me at the crossroads? What would it be like if each woman had made the choice that worked for her and gone on to live a life she chose? In this version of the story, I have both their wisdom in my ears, warm arms around my shoulders, soft hands gripping mine. I hear Martha’s voice and I smell Enola’s perfume. Whichever path I choose, a grandmother walks beside me, guiding my way and keeping me safe on my journey.

Instead, Martha walks down a single path with me, and you can see her gloss on my life ever since.

I chose a path. So what is the purpose of returning to that crossroads? Why revisit the choice to get married and graduate at the same time, to watch that infinitesimally small bundle of cells turn into a baby, and a child, and a woman—a choice that, knowing who was about to come into my life, I would make one hundred percent of the time?

I know enough to feel grateful that I got to make a choice at all, even if my choice was to go with what I knew. I was educated, and my family could have helped me. My partner was supportive. I knew abortion was available to me if I wanted it. I was given information and could afford to get it. Nobody tricked me or stalled me or shamed me.

In fact, I had more options twenty years ago than millions of young women do today.

And that’s why I’m returning to this crossroads: Enola is still there, trapped in the aftermath of her own choice. She lived at a time and place where her choice was a desperate choice, whatever the reason. She deserved and deserves better.

Marcella White Campbell, a San Francisco native, is, in no particular order, a Black woman, a mother, a Jew, a wife, and a writer.