Girlhood in the Early Aughts

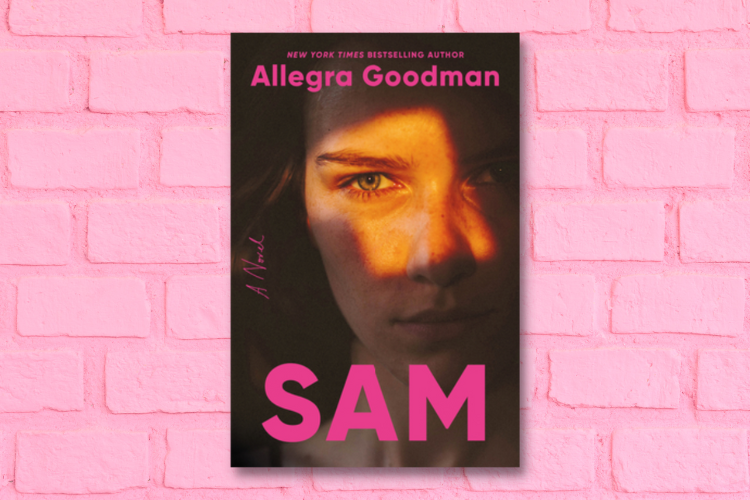

In her finely observed, moving new novel, Sam (Dial Press, $28.00) Allegra Goodman explores the psychological complexities of girlhood in early twenty-first-century small-town Massachusetts.

When we first encounter Sam (just Sam), she is in second grade. School drags on. Lessons are incomprehensible. Little brothers are annoying. Teachers are preoccupied. Fathers disappear. The girls in her school care about things Sam doesn’t understand. Sam’s mom has zero support and less money. Her mother’s boyfriend barely acknowledges her, and then when he does, it’s with barely sup- pressed violence. Through Goodman’s tightly controlled point of view, which matures along with Sam, we fully inhabit Sam’s world, a world where “nobody tells the truth—not really. You’re supposed to know, or guess, or just get older.”

Fortunately for Sam, she does get older, and finds a passion for rock climb- ing, friendship, and love, with the reader along for the ride.

Central to the book is how families— women and children especially—fall through the cracks in society. Bad marriages, bad boyfriends, jobs that barely pay the bills, and a society indifferent to the plight of women and their families. At times it’s a painful but important read, exposing bare tacks of issues that can feel, for a lot of Americans, to be abstract. Sam’s best friend lives on the other side of town in a big house where the father makes pancakes and a mother who isn’t too exhausted to ignore a little mess, and Sam finds respite there. When this friend goes away to boarding school because she’s bored in the classroom, our hearts break for Sam, who will be left behind. It begs the question we should all ask ourselves in this country: why the friend and not Sam? Sam is bored in the classroom too. This is not the story of a bright academic young girl tapped by teachers early for scholarships and other enrichment opportunities for kids from broke and broken families. It’s far more interesting than that.

Sam’s mother, Courtney, provides the beating, bleeding heart of this book. She’s exhausted and cranky and willfully misunderstands Sam—who, in turn, shirks the trajectory Courtney has mapped out for her. But she’s doing the absolute best that she can for her family, sacrificing every comfort and scrap of personal ambition for a toehold in something that feels like security. Sam’s dad is trying too, but he’s failing more than he’s succeeding. He certainly seems magical to young Sam, pulling coins from behind her ear and rabbits from hats. He can play every instrument and always knows the right thing to say to cheer up his young daughter. But the only thing he cannot conjure up is the one thing she so desperately wants: stability. Showing up when and where he says he will. “Were you ever in love with the wrong person?” teenaged Sam, grappling, asks him. “Usually I was the wrong person,” her father replies.

The closed grip of childhood eventually opens up. We grow up with Sam, her heartache, her disappointment, and later, the blessedly numbing effects of young love along with a smattering of the usual intoxicants. She finds respite in a passion for climbing. “Stop,” Sam says in the book, “don’t put me in your metaphor.” It’s no use. By the end of the book we want her to succeed so much we’d carry her up life’s boulders on our backs if we could.

Bethany Ball’s novels are What to Do About the Solomons and The Pessimists both published by Grove Atlantics.