From the Editor

Jewish men are lucky to be married to women.

For my 1989 book Intermarriage: The Challenge of Living with Differences Between Christians and Jews, I spoke to hundreds of partners in interfaith marriages. These interviews cast light on some gender differences—both obvious and more subtle—which still seem to play out today. Three first-person articles in this issue begin an updated look at women dealing, one way or another, with these relationships. Women and men reacted differently to many of the situations interfaith couples face. What’s more, there were additional differences I saw when the Jewish partner was the woman. In marital choices, as in so much else in life, a gender lens refracts a score of other issues. Among them: Jewish women are less likely than Jewish men to want to marry non- Jews. Fewer women intermarry than men do, which means more Jewish women than Jewish men remain single.

Jewish women married to Christians were often blamed for not ensuring that their children would be raised Jewish, while Jewish men seemed to get off without opprobrium if the kids chose not to identify as Jews.

And interfaith couples where the Jewish partner is female may experience a very different dynamic from couples where the man is the Jew. It is difficult for many Jews to say what matters to them about being Jewish. For many, Jewish identity doesn’t include a credo, so defining what it means to be Jewish can be very challenging. But because women are permitted to tune in to their intuition more than men, non- Jewish wives say they pick up on signals from their partners that aren’t explicitly articulated—like why it matters to a Jewish husband that his children be raised as Jews, or at least with a sense of their Jewishness, even though he may say that attending services isn’t important to him, or that Jewish rituals and celebrations don’t matter. In other words, Jewish men are lucky to be married to women.

Fourteen years ago, the Jewish world was rocked by the 1990 National Jewish Population Survey that revealed about half of all Jews getting married were marrying non-Jews. Much of the quantitative data buttressed what I had observed from the couples I’d interviewed for Intermarriage. Now, with the September 2003 release of a 2000-01 survey of American Jews, we have evidence that, though Jewish women are still less likely to ever get married than other American women, the percentage of Jews marrying non-Jews has increased only slightly since the 1980s. Perhaps the new survey data will allay some of the collective number-panic pervading the Jewish world for the last decade, and we can nine in, past the static, to hear about the emotions and experiences—the human stories behind the statistics—of Jews in interfaith families.

In Lilith’s pages in this issue, a feature entitled “Halves” explores the Jewish identities of three women in their 20s, women on the edge in different ways.

• A woman who always considered herself a Jew gets the news one night from her Orthodox rabbi that she’s not. She tells why she, her mother, and her identical twin sister react differently to this unwelcome news.

• Another author is the adult child of a nominally Jewish father and a “recovering Catholic” mother. She calls herself a “Half-Jew,” and reports a new identity category for the 66 percent of the children of intermarried parents not being raised to name themselves “Jew.” She gives us a preview of how her cohort will choose their own partners.

• A third twenty something woman checking in with us is the Jewish half of an interfaith marriage. She explores what it feels like to shift the locus of power in her extended family. For the first time in generations—maybe ever—the Jewish expert is female.

These three strongly worded stories bring us into realities barely hinted at by the survey data. And they represent, I think, a new kind of writing that we’re seeing more and more frequently at Lilith. While a few years ago the topic explored most often by Jewish women was the history of our fore mothers—sometimes scholarly, sometimes sentimental, always heartfelt—the magazine now is a also magnet for first-person articles which combine powerful narration with an analysis of what life experiences of this moment can teach us.

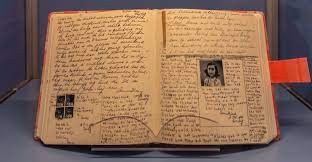

Had she not been murdered, Anne Frank would be turning 75 in a few months. With Lilith’s Anne Frank section in this issue we look back not just to Anne’s era but also to the teen years of women who have come of age in the years since. We turned to readers from all over the world— South Africa, Israel, Europe, the FSU and North America— to see if we could understand more fully the powerful hold this book has on so many Jewish women writers and thinkers.

I was focused on The Diary of Anne Frank when, coincidentally, a reporter called me the other day to ask what Jewish book had most affected me. Without pausing to ask her what she meant exactly by a “Jewish” book, I answered, quite spontaneously, ”Marjorie Morning star’‘ And then I had to ask myself “Why that book?” Answering the question (for myself and for her), I realized that Herman Wouk’s Marjorie Morning star represents to me not great literature, but rather a benchmark for how Jewish women were perceived and portrayed by a male writer of influence, and thus how we were forced to see ourselves in an era that seems far removed from the nastiness and venality in later literary renditions of the Jewish American Princess.

Marjorie, apple of her family’s collective eye, transgresses in thought and deed (aspirations to a career in the theater and a pre-marital affair, as it was quaintly called in the 50s), but in the end she makes conventional choices. The book and the hugely popular film which followed remain for me like a set of stone tablets on which the world carved the limits set forth for an intelligent and hopeful Jewish daughter. Interestingly, though Marjorie appeared at almost the same time as The Diary, the images of young women partisans in the forests and teen-aged resistance heroines in the ghettos were not yet embedded in the consciousness most North American Jews. So Marjorie Morning star is for me a punctuation mark. It’s the end of an era, a pause coming before the works spoken and written in the voices of Jewish women themselves, penning (or typing) their own narratives, in the 1960s and after.

Amplifying the stories Jewish women tell in their own strong voices continues to be a prime reason why Lilith exists. It’s also why I hope you will want to make a generous tax-deductible contribution (see Lilith’s address and phone numbers to your left) to help sustain this unique magazine in its mission.