Four Photographs of Rukhl

There are only four photographs of Rukhl, and I have never found anyone who knew her. She was my father’s first wife, the mother of his son, Avrom. One day, mother and child disappeared from this world, and no one has ever told their story. This task has been on my life-list; it falls to me.

Rukhl’s maiden name was Kalb, and her nickname Ruzhie. She had two brothers, Meylekh and Aaron, and a sister, Miriam. She and my father, both born in 1909, came from a kleyn shtetl in the Carpathian foothills of Galicia, Poland (then Austro-Hungary) that the Jews called Isterik, and the Poles, Ustryke Dolne.

The first photo shows Rukhl in 1930, in a group portrait of the Jewish drama club of Isterik. Young adults, in their late teens and early twenties, posing against a pastoral backdrop. My father, Israel, then called Srulke, is in the middle row, center, between two dark-haired girls. He wears a fancy suit and tie, and still has some hair. Above him, and just to the left, is Rukhl; square-jawed, serious, challenging the camera.

Because I know something about this time and place, I recognize that the clothing on these young folks, though ordinary-looking, bespeaks a revolution. Even 10 years earlier, Jewish girls this age would have been buttoned to the neck; the boys would have sported beards and head-coverings. The parents of these mode nouvelle-niks abruptly became a distant generation. Still Orthodox, they wore shaytls and long sleeves, long beards and talis kotn.

The photo captures a breathless new world, though you can see that the males in the club still outnumber the females two-to-one. It was still shocking for a Jewish girl to act in the theatre.

In the bottom row, a young woman holds a sign in Yiddish: “An-sky Drama Club.” S. An-sky, who wrote the gothic-Hasidic play The Dybbuk, was an ethnographer and leftist polemicist who lost his original manuscript as he fled Bolshevik Russia; he later reconstituted the Yiddish from Chaim Nachman Bialik’s Hebrew translation. An-sky had toured my father’s region of Galicia between 1911 and 1914, gathering fading Jewish legends.

According to my father’s memoir, written in 1984, the year before he died (which I have translated, but not yet published), he and Rukhl first met when she was a volunteer librarian at Isterik’s I.L. Peretz club, a literary organization named after the seminal Yiddish writer. Rukhl introduced Srulke to the world of “good writers,” my father said; an arousing experience, no doubt, for a young man whose formal education consisted of one year of mandated secular schooling in Hungary at age six (my grandmother had fled to her mother’s house there as World War I raged from 1914 to 1918) and tiny bits of Orthodox Jewish schooling from the age of 3. My grandfather, a poor bal agulah (wagoner), only occasionally had the pittance for a melamed (teacher).

I.L. Peretz had a literary salon in faraway Warsaw where he nurtured younger writers and readers, daring them to flee the restrictive confines of Orthodox yeshivas. For my father and Rukhl’s generation, their rural shtetl was a desperate dead-end: no jobs, no education, no chance for mobility of any kind. Rukhl introduced Srulke to literature translated into Yiddish — Jules Verne, Victor Hugo, Jack London — and Yiddish classics. The magic in these books must have stunned and transported them.

My father’s rebellion began, he told me, with furtive shabbos cigarettes smoked behind the shul. Why behind the shul, I don’t know. Before long he was eating bacon; specifically, he said, to defy his father. Throughout his life, my father kept kosher, never mixing meat and milk, or eating shellfish. His bacon-eating, though, remained foundational. His little brother, Moishe-Aaron, had had a tumor in his throat, but their father refused the recommendation of greasing the toddler’s esophagus with bacon fat, and my father watched Moishe-Aaron choke to death. When I was grown and my father lived in Israel, I knew to mail him tins of bacon so he could stay faithful to this protest.

In 1930 or 1931, Rukhl, age 21, got the chance to dump Isterik and move into her aunt’s apartment in the closest big city, Krakow. Shortly thereafter, my father was drafted into the Polish reserves for six months (the Isterik Jews becoming Polish, not Austrian, citizens overnight), and he often told me that he treasured that time, not only for its abrupt freedoms, but for his having, for the first time, enough to eat. Upon his release, he went straight to Krakow, showing up at Rukhl’s aunt’s apartment with only the clammy woolen uniform that was on his back; it was a sweltering summer day.

The apartment consisted of one cramped room with three beds, a sink and a coal stove. Rukhl’s aunt and uncle slept in one bed; Rukhl and her sister Miriam in another; and in the third slept Miriam’s boyfriend and my father. Rukhl and my father believed in “free love,” though, so they managed, I assume, to find private moments.

Work in Krakow was very hard to find. Rukhl and Miriam, though, worked ceaselessly as tailors, and my father was lucky to find work for an upholsterer as a “human mule,” as he called it, carrying heavy sofas to and from customers. Occasionally the good-hearted upholsterer let Srulke watch him work, and my father acquired the skill that would become key to his survival.

Miriam had a baby, and because her income was vital to the family, she hired a poor girl from Isterik who came to live in the crowded Krakow apartment to tend the infant. One day, though, the girl fell asleep, the crib collapsed, and the baby died. Miriam became severely depressed. My father’s mother, an herbalist, sent her St. John’s Wort to bathe in, but it didn’t work. Miriam, in her depression, was also refusing to have sex with her husband, and the latter finally consulted a rabbi. He mandated that my father and Rukhl forcibly hold Miriam down while her husband raped her. So they did. My father was traumatized by this. I can only imagine what it was like for Rukhl, not to mention Miriam. Miriam conceived, though, and had another child.

After two years of living together, cramped and stressed and poor, Srulke and Rukhl decided to marry. It was 1933, the year Hitler came into power in Germany. The nuptial couple, returning to Isterik for Passover and their wedding, discovered that Rukhl’s mother had just died from “overwork” — from the backbreaking threshing and grinding and trudging and hauling and whitewashing and scouring and kashering required of Jewish women in preparation for Pesach. Shortly thereafter, my father lost his mother as well.

The second photo I have shows husband and wife sunbathing in a park, the Krakow castle visible in the background, Rukhl looking pregnant. My father has less hair. They look well-fed and happy.

I know that they had their own apartment by this time, a fixer-upper, and that my father had steady work in his trade. The two of them were politically active in the Bund, the Jewish-Socialist organization that stood for a shiny proletarian future in which Pole and Jew would be comrades forever.

Ah, yes, the third photo. Rukhl is in the middle — happy and fat, looking prosperous and fashionable; her baby on her hip. I believe this is the only photo proving the existence of Avrom, proving that I had a half-brother. He has big ears. My ghost-brother had big ears.

My father and Rukhl are paying a visit to their shtetl Isterik here (I can tell from the rustic-looking fence), and Rukhl and Avrom are posing with my father’s brother, Yosl, his wife, whose name is lost to me, and their son, Getzl.

Rukhl, I think, is more expensively dressed than her sister-in-law; she’s an urban sophisticate. Yosl stayed in Isterik, but it looks like he did okay, too, cobbling and making boots.

The fourth photo. This photo just came into my possession, and I am still in shock. Sixty-five years after acquiring the other photographs! The first three photos survived the war only because my father had sent them, during the up-and-up years, to his brother Calman, who left Poland in the 1920s to settle in Montevideo, Uruguay. Uncle Calman mailed them back to us when we arrived in Canada, in 1948. It strikes me now that this was a very empathic thing to do, bespeaking helplessness. He knew the family had lost everything, so he mailed us our past.

At the end of the war, my father returned to his apartment in Krakow. He’d spent the war in a gulag in Russia, then in Kyrgystan; then he enlisted in the Soviet army to fight the Germans at the front.

He had already stopped in Isterik and found not a single member of his family alive. When he knocked on his apartment door in Krakow, he told me his heart had left his chest, that he knocked in a trance of dread. But when the door opened, all of his familiar furniture was in place, his pictures on the walls, everything exact, as though not a day had passed. But the woman who opened the door wasn’t Rukhl, nor the child Avrom. He said the neighbors, hearing a hubbub, opened their apartment doors and looked, astonished, like they were seeing his ghost.

The municipality had given his apartment to a widow with a child. One neighbor told him that Rukhl had been seen once in a forced labor detail, sweeping the streets. She sneaked over for a moment to beg for bread and was never seen again. I wonder if she got her bread. My father’s wife and child were gone without a trace.

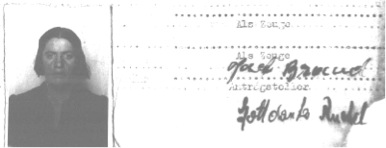

So, this last photo, this last photo. It came to me because of the persistent scrounging of Michlean Amir, a librarian at the U.S. Holocaust Museum in Washington. In a loose-leaf folder labeled “Krakow,” she found Rukhl’s work document, a “Protokoll” — whatever that is — dated February 2, 1940.

In September, 1939, Rukhl’s and Srulke’s world had abruptly come crashing down. The Nazis were on their way, they were told, and Srulke, a well-known activist in the Bund, was particularly endangered. Rukhl sent him running into the woods where she thought he might be safe. Some weeks later, he tried to creep back towards Krakow, but he was arrested by the Russians as a fifth columnist and sent into forced labor in Ukraine.

From this “Protokoll” I learn so little. It’s written in German, signed by a “Josef Brand.” I see Rukhl’s address: Saltyka 5, Krakow. I’m not sure if that’s the address of Rukhl’s and my father’s apartment.

It’s an I.D. photo. A woman looks out, haggard, eyes sunken and dead, yet still alive with tragedy. A woman who has lost everything and also hope. At the time the photo was taken, had she already seen Avrom starve or be killed? A lingering fantasy of mine always puts him into hiding. How anyone could kill children, I could never understand. Rukhl’s husband is gone, perhaps alive somewhere, her whole family unreachable, perhaps dead. She doesn’t know. She is only 31.

There is little doubt that she did not survive. People in that kind of slave labor were specifically worked until they starved to death, or died of illness or misery.

What is left of you, Ruzhie — librarian, actress, square-jawed, serious girl whose gaze tested the camera? Daughter, sister, activist, wife. Mother. Very young woman. What is left of your passions and struggles?

All that remains are four photos of you, these, and my father’s scant brushstrokes in his memoirs. In these photos, though, you still look out at me. Would we have had much to discuss if we had met? But how silly of me, our existences are mutually canceling. If you had survived, I would not exist.

But I am the only one who can leave this testament to your life and your suffering. So I do. In full faith, I do.

Miriam Isaacs was born in a Displaced Persons Camp in Germany, grew up in Montreal and Brooklyn, and taught Yiddish language and literature at the University of Maryland. Her research includes Yiddish publications in postwar Germany and Yiddish-speaking Hasidim.