Fiction: “Hawaii and Mexico”

WHAT DID KEVIN DRESS LIKE?”

Oren asks, as we drive home for the weekend. Oren, who is 24 and has autism, lives in a group home in the country during the week. On the ride home to Jerusalem on Friday morning, he likes to talk about what he remembers from New York 20 years ago, before we moved to Israel. This week, the trees are displaying the tepid Israeli version of fall foliage and Oren knows that the Jewish holidays have just ended and the next big day on the horizon is Halloween. No one really celebrates it in Israel, although after we first moved to Jerusalem, I used to give the neighbors candy to hand to him and we did a version of trick-or-treating. Now, he marks it by remembering the exciting Halloweens we had with our neighbors on the Upper West Side.

“Kevin dressed like a butterfly,” I answer. Kevin was a very straitlaced guy who worked at an insurance company, but when Halloween came, he dressed up for the party thrown by our other neighbors, Rob and Mike. Kevin wore one of those mask/ hat combos with something like antennae that wobbled in all directions and a delighted Oren decided he was supposed to be a butterfly. We still have pictures from this party, which Oren will look at as soon as we get home.

We pass some satellite dishes in a field that is still mostly green and Oren remarks on them, but he quickly goes back to that party.

“What did Mike dress like?” he asks.

“A cowboy.”

Mike and Rob are a gorgeous gay couple who are so coo there is a documentary about them. Really. Today, of course, they are legally married and their daughters are in high school and college. Oren still likes to look at the DVD of the documentary. It’s called Paternal Instinct and it tells the story of how they had their two children with a surrogate back in the early 2000s, when that was a new idea. Oren likes to describe what they are wearing in the pictures on the cover: bathing suits, a Santa Claus outfit, tuxedos, etc. And he talks about them: “Mike is tall and Rob is also tall.”

At the Halloween party Oren remembers, when he was three, Mike looked like a movie star playing a Chippendale’s dancer, shirtless, in tight jeans and boots, with a red bandana around his neck and, of course, a cowboy hat.

“I see a black Suzuki Alto,” Oren says as one passes us on this deserted country road, but he is only momentarily distracted. “What did the lady dress like?” he asks.

The “lady” was Rob, all six-foot-four inches and many Norwegian ancestors of him, in drag. I used to try explaining that to Oren, but he always calls the costumed Rob “the lady,” and doesn’t admit he knows it was Rob.

“What did the lady dress like?” I repeat, because I like to hear his answer.

“Hawaii and Mexico,” he says. I’m not sure what combination of images and photos sparked this response, but Rob was trying for Hawaii, with a grass skirt, coconut-shell top, colorful lei and long blond wig. He carried a ukulele, an instrument Oren must associate with Mexico, for some reason.

“Who was the lady?” I ask, hoping he’ll get it, knowing he won’t.

“The lady dressed like Hawaii and Mexico. What did Abba dress like?” he asks. Abba is the Hebrew word for father. I was still married then and Oren had just been diagnosed with autism the day before Halloween.

Abba wore a top hat. “Fred Astaire,” I say. Oren once had a therapist in Israel who used his love of music and dance to teach him about all kinds of related topics, including Fred Astaire.

The feelings of that time, of that party, all come flooding back. His father didn’t want to go. He was angry about Oren’s diagnosis, in mourning. “I’ll never forgive you for what you did to my son,” he said as we walked out of the office of the psychologist who told us Oren had autism. I was frozen by the shock of it, the uncertainty of what it meant, of what Oren’s future would be. And the certainty, that I tried to ignore, that my marriage was now over.

“You’re seeing Abba on Saturday night,” he says, mixing up “you” and “I” as the autism makes him do sometimes.

“I,” I say.

“I’m seeing Abba on Saturday night,” he says. Sometimes I think he mixes up the pronouns on purpose because he enjoys the ritual of me correcting him.

“We’ll see,” I say. I sent his father a message four days ago. It usually takes him 72 hours to respond to a “yes-no” text about whether he will have dinner with Oren on Saturday night, but this time it’s been longer. Anger makes me grip the wheel tightly. He almost always is free to see Oren one weekend night, but there are just enough times when something comes up that I don’t feel I can tell Oren yes for sure. He’s 24 and he sobs when he can’t see his father.

“I’m seeing Abba,” he says.

“I think so.”

The traffic ahead of us slows and I feel myself cooling down.

The anger still overwhelms me at times. I know all the reasons that it shouldn’t but it does. It happens more now that Oren is in this new group home. It’s a great place, the only place I found that still tries to teach, to help them keep developing. When he first “aged out” of the education system and was banished from his wonderful school at 21, we put him in a place that was all wrong for him and almost every waking moment and quite a bit of my sleep was consumed with figuring out how to create a better future for him. It feels as if I have been running a marathon for more than 20 years now, since he was diagnosed the day before that Halloween party. Now, the finish line is in sight. In the moments when I allow my mind to rest, though, the hurt I feel over the accusation that I caused Oren’s autism—meshed with the inner fear I will likely never shake that it’s true, his autism is my fault, somehow—comes crashing down, inconveniently.

Just like that, Oren is back to the Halloween party, asking, “Eema, what did you dress like?”

I wore Mickey Mouse ears. “Minnie Mouse,” I say. “What did Ben dress like?”

Ben is Oren’s younger brother, who was about a month old when this party took place.

My answer has to be high-pitched or it doesn’t count. “A tiny baby lion.” We had been given a lion costume for him, a onesie with a hood. He’s asleep in all the pictures.

“Rob and Mike had a rainbow flag,” Oren says.

“Yes, they did,” I say.

Rob and Mike were hoping to have a baby already then, in a first attempt that ended in a miscarriage, and the camera crew for the documentary was there. Their Halloween parties were spectacular, the crowd spilling onto their terrace, which, as Oren correctly recalls, was draped with rainbow flags. What I remem- ber and Oren apparently doesn’t is that the bartender was naked except for a well-placed leaf. That’s what I like to remember, a crazy, sexy New York party.

What I don’t like to think about is what Oren’s costume was that year, toddler-sized scrubs that a friend gave us, because he and Oren’s father were both doctors and it hadn’t seemed implausible to him that our little, bright-eyed son might be a doctor, too. A week before the party, when we got the scrubs, it hadn’t seemed implausible to me, either. I didn’t think there was anything really “wrong” with Oren, I just thought he talked oddly and was hyperactive, problems that would disappear as he got older. Even after the diagnosis, I held onto hope, though, since no one could say anything conclusive about his long-term prognosis. I decided, stupidly, that I was going to be happy about everything: my beautiful lively son, our sweet baby, my wonder- ful job, and even my marriage that would repair itself when we were out of this temporary, stressful period.

Their father acted as if I had lost my mind when I came home from work with mouse ears for myself and a top hat for him, announcing that we were definitely going to Rob and Mike’s party on Saturday night, and maybe I had. But Oren was so cute in his blue-green scrubs and plastic stethoscope. The day after the party, I had to throw out the lion onesie for the baby whom I now knew had a 20 percent chance of also having autism. It gave Ben a rash.

Just past a town called Tzur Hadassah, the road narrows and for about 15 minutes, and you drive through the West Bank. I’m not nuts about doing this, I know there is stone throwing here sometimes, although it’s usually at night and has never happened to us. But it saves about 20 minutes of driving on the main highway or about 10 minutes on a very treacherous, curving road, and I’m Israeli enough now to deny the danger and take this route.

The first sign we’re in the West Bank is a settler jogging with a full beard, a black kippah, black pants and tzitzit flapping in the wind on one side of the road, as an Arab man on a white donkey goes by on the opposite shoulder.

Rob and Mike and their girls wouldn’t be welcome on either side of this road, among the ultra-Orthodox or the Palestinians. They would fare better in our neighborhood in Jerusalem, but, sadly, not much. If they lived in Israel, they would be in an apartment in Tel Aviv or a house in the country.

“There’s a donkey,” says Oren, but quickly he’s back to Halloween, asking, “What were the decorations?”

“You tell me.”

“The purple lights.”

Even when Oren was just 18 months old, he stared in wonder at the long row of purple lights in our hallway. Every year, Rob and Mike unscrewed all the lightbulbs the week before Halloween and replaced them with purple ones. The older Oren got, the more interested he was in them.

“Police jeep,” says Oren.

A border police jeep pulls over a grimy white car in front of us and Arab men who look like laborers spill out. A mangy dog darts into the road and behind a barbed wire fence stands a white mosque that is a miniature replica of the Dome of the Rock.

“Rob and Mike put up the purple lights,” Oren says.

“Yes,” I say.

Oren and I, with Ben in the snugli, had been admiring the

purple lights in the hallway, after their father had left to go to work on the Sunday morning after the Halloween party. I wasn’t sure he was really going to work. Except for a few functional sentences, he was not speaking to me. But it was going to be all right, because we would figure out what to do and Oren was going to be ok. And although I hadn’t had the energy to get any of us dressed yet, we were going to have a great day because everything was always going to be great.

“Abba!” said Oren, looking in the direction of the elevator into which his father had just disappeared.

“Abba had to go to work. He’ll be back.”

“He’ll be back,” Oren said.

“Let’s look at the purple lights,” I said.

“The purple lights,” Oren said. He always talked, that was one of the reasons it had been hard for me to understand that he was autistic.

Just then, Rob emerged from their apartment, carrying a bag of garbage which he took to the incinerator, and Oren ran to him. “Hey, Oren-man,” Rob said, scooping Oren up, as Oren giggled. I asked how they were managing with the cleanup, and thanked him for inviting us to the party.

Rob looked at me.

“What’s wrong?” he said.

Tears splashed down my face. Before I knew it, I was sobbing on his couch as Mike brought me coffee and Rob held Ben, while Oren played with their toy police car, which had a loud siren and a policeman’s voice yelling at a suspect to freeze. One of their cats came up to Oren and he said, “Hi, Topo.”

Mike and Rob said every nice thing in the world to me and Rob topped it off with the words I carried close for 20 years: “I understand he has this diagnosis. But don’t you know he’s the warmest person in the world?”

WE PASS A TRAFFIC CIRCLE that leads to a town in Area B, the mixed Israeli-Palestinian controlled area of the West Bank, and there is a pushcart that sells Turkish coffee where I am always tempted to stop but never do. We move into one of the lanes that lead to the checkpoint into Israel.

“Oops! There’s a little bit traffic,” Oren says. “Not too much,” I say. It’s always slow here. “Mike is tall and Rob is also tall,” he says. “Very tall.”

“Very tall. Their cats were Louie and Topo. And now they have baby Amelia and baby Lynn.”

I last saw them when I was visiting New York by myself in 2012. Amelia was 10 or 11 and Lynn was 7 or 8. They had already moved upstate but were taking the girls for dim sum and shopping. I met them in Chinatown. There isn’t a day that Oren doesn’t look at those pictures. We ate the dim sum and I went with them to a department store. They asked me to take the girls into the dressing room and help them try on the dresses for Easter. We sent them pictures from inside the dressing room on their smart phones. Amelia wanted something a little frillier than they would have liked but they agreed in the end. I felt honored to be part of their family life if only for a day, to do one of the only things gay dads can’t do, accompany their daughters to a women’s dressing room. I tried on a dress and some jeans and the girls told me I looked great. The jeans turned out to be the most flattering pair I ever owned in my life and I felt those two girls, who were so sweet and so much like their fathers, had brought me luck .

“They’re not really babies anymore, Oren,” I say. I’ve tried to show him current pictures of them on Facebook. They are in their mid- to late-teens now. But he doesn’t want to see them as teenagers. He still enjoys thinking of them as babies.

Two cars ahead of us is a van with Palestinian plates. The soldiers open the back and make everyone who is inside get out. Israeli drivers zigzag in the lanes leading up to the checkpoint, trying to avoid getting stuck behind this kind of a vehicle, but I am never quick enough for that. My phone beeps and I see that it’s Oren’s father, answering my message about Saturday night.

“Great, happy to see him,” he writes. “You can see Abba,” I tell Oren.

“On Saturday night,” he says.

IN THE DECADES SINCE that Halloween party, I’ve tried to forgive Oren’s father for what he said, for blaming me for something that just came from out of the blue. Last night, I couldn’t sleep and was watching Manchester by the Sea on TV. I flash back now to the scene where the mother runs into her ex, who made a stupid, drunken mistake years before that killed their three children.

“I said a lot of terrible things to you, but I know you never— maybe you don’t want to talk to me. Let me finish…My heart was broken, ‘cause it’s always gonna be broken. But I know yours is broken, too,” she says.

I’m not sure, in our scenario, who is who. Oren’s father has apologized for blaming me and I also said a lot of terrible things to him over the years that our marriage—which, it seems to me now, was never good—limped along following Oren’s diagnosis. We still have the bond of Oren—nobody else will ever know quite how our hearts were broken by the diagnosis. I know that it’s not politically correct to say that you mourn an autism diagnosis, but now that I no longer have to find a place for Oren, no longer have to worry about getting him settled, I feel the sadness that I couldn’t feel before about all the things that he will never…I have an impulse to send their father a text saying something that is neither snide nor aggrieved and pick up the phone. But the soldiers have let the Palestinians back in the van and the traffic is moving again. I put the phone back on the seat.

As we roll up to the checkpoint, the soldiers, two guys and a girl armed to teeth but more interested in flirting with each other than looking at our car, wave us through and we join the traffic crawling through the two long tunnels that lead to Jerusalem. Oren is happy to get stuck here. He loves tunnels, they are one of his favorite things, and being in and around them makes him especially alert and talkative.“The lady dressed like Hawaii and Mexico,” he says.

“Yes, at the Halloween party.”

We emerge from the first tunnel.

“We’re on the tunnel road,” he says. “There are two tunnels.”

“Yes,” I say.

“The lady was Rob.”

Hannah Brown is the movie critic for the Jerusalem Post and the author of the novel If I Could Tell You.

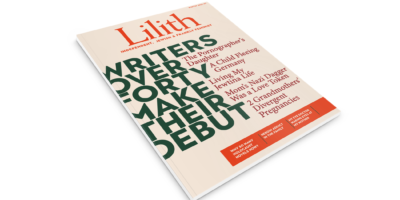

ILLUSTRATION: LINDSAY BARNETT