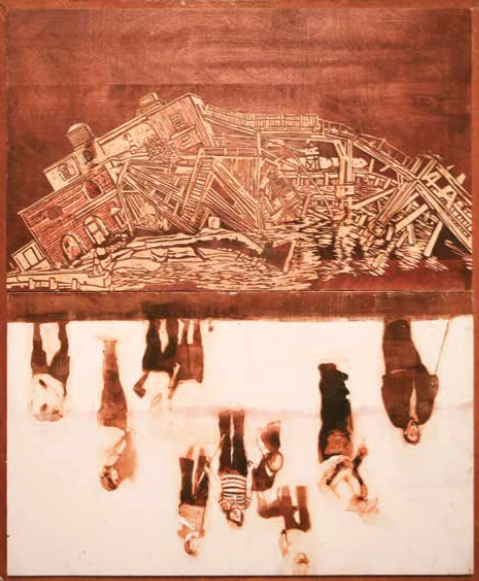

Blame

Art Credit: Nivi Alroy

Irit stood outside her office, took a deep breath, and considered the sign on the door: “Bereaved Families for Peace.” The “Bereaved” part had been Ali’s idea; the “Peace” part hers. Ali didn’t want a political name for the organization. Irit countered that peace was not political. She opened the door and entered. “I need you. And a cigarette,” she said as she took off her bike helmet, coiled her long, graying chestnut hair into a clip, and dropped her backpack on her desk.

“Which first?” Ali asked. He was sitting at his desk, working on the computer, but he pushed his chair back and stood. He was usually the one to open the office, since he had no kids at home to get off to school, and she had 13-year-old Yotam.

“In the order mentioned.”

Ali took Irit’s hand and lead her to the pull-out couch. But he did not pull it out. Instead, he sat her down and massaged her neck and shoulders. This was their bed. Ali lived in Jaffa, a few kilometers away from the office, and Irit in Tel Aviv. The office was right on the border.

They had been best friends, then lovers for years, and on the anniversary of their first kiss every year for the past decade Ali asked her to marry him. But Irit did not want a replacement husband, nor a replacement father for her boy. Life with Elie had been one thing, and this was another. Besides, she was in her forties by the time Ali asked the first time; more kids were not going to happen, so she did not feel pressured to marry again. The office was where she and Ali were a couple, not in their separate lives.

“Do you want to talk about it before? Or after?” Talking was how they had first connected, she and Ali. It was the spark that started Bereaved Families for Peace. Their spouses had died one day apart—Elie, and Ali’s wife, Saida. Elie was shot and killed returning from driving his parents home to the Occupied Territories one night after they’d visited for the weekend. In retaliation, a Jewish settler shot at Ali and Saida driving home to Jaffa from visiting family in Ramallah. Ali survived. His wife did not. She was pregnant with their first child.

Irit and Ali met standing on line at one of the various government offices where they were required to report their spouses’ deaths officially—that period in her life was a blur, and there was so much bureaucracy! Ali had overheard Irit speaking with the woman at the desk, seen her break down in tears when the woman asked how Elie had died, and heard her yell at the woman when she was handed piles of forms.

“I shouldn’t have to do this!” Irit had shouted. “Let our moron of a war-monger prime minister fill out these forms!”

She had not mentioned her in-laws, how they’d insisted Elie drive them home, despite Irit’s concerns about driving on those roads at night in the middle of yet another intifada. But she had considered mailing them the forms when the woman at the desk started crying too, saying she was simply doing her job.

Ali had taken his forms and asked Irit if she would accompany him to a local coffee shop, where they could fill out the forms together. And that was how Bereaved Families for Peace was formed. Over coffee and tears. The sex came months later.

Irit looked into Ali’s big brown eyes and stroked his stubbly cheek. He looked like an Arab version of Elie—tall and lanky, curly dark hair, disheveled in an endearing, sexy way—But unlike Elie’s, his heart had been hardened. Like hers. And then cracked opened. Like hers. Then his was softened. Whereas Elie had been born that way. With a soft and open heart. Irit’s was still hard and still cracked open. Soft was not in her repertoire.

“My father-in-law moved in with me for a few days,” Irit told Ali as he rubbed her fingers between his. She said this matter-of-factly, as if she was announcing an impending heat wave. “With his Filipino aide, Muno.”

“What do you mean, moved in?”

“I mean that he’s sleeping in my bed. On Elie’s side.” “Lucky man. You’ve never even let me get close to that bed.”

Ali stroked her cheek now.

“Ali, this is the man who spoke at the U.N. against a Palestinian state. The man who said Palestinian boys were born with stones in their hands! As you very well know.”

“Ouch!” Ali put his hands to his heart and grimaced in mock pain, as if he had been stabbed. “So why is he staying with you?”

“Muno wants a few nights off to spend with his girlfriend in Tel Aviv. It’s their anniversary. If they stay with me, Muno can still be nearby if needed in an emergency. He can work during the day while I’m out and have the rest of the time off when I get home. For some reason I cannot fathom, my father-in-law loved the idea. I thought he couldn’t stand me. The secular, left-wing whore who stole his misguided son. Just the thought of my father-in-law in my house gives me a migraine.” She moved her hands up to her temples and started making circles where she felt the pain starting. “You know what happened last time Elie’s parents stayed over….” Her voice trailed off.

Ali reached over to his desk for a box of cigarettes. “Can you find any compassion in your heart for this man? He did, after all, lose a son.”

“Despite common assumptions, losing a spouse is harder than losing a son.” If she had lost Yotam instead of Elie, at least she would have had a partner in pain, someone to carry it with her. Yotam did not even remember his father. “And he had five decades with his wife before she died. I barely had half a decade with my husband!”

“I thought we don’t rank pain in our line of work,” Ali said, offering Irit a vape pen.

“It’s useless. The important part is just to acknowledge that we all have pain.”

Irit pushed the vape away and started unbuttoning Ali’s shirt. She’d smoke the dab pena only after she’d had Ali. “That is our motto, isn’t it? But I can’t get past my anger at the both of them, even with her in the grave, buried next to Elie, for God’s sake! He’s buried next to his murderer!”

“That’s extreme,” Ali murmured. “You can forgive the entire Palestinian people for the murder of your husband, but not his own parents for their unintentional involvement that exists only in your convoluted understanding of who’s at fault! I love you, but I really don’t get you!”

“Guilt, Ali. Guilt. My people killed Saida. That’s why I can forgive their murdering Elie. But I did nothing to my in-laws but marry their saint of a son, who was devoted to them beyond my comprehension. He compromised his politics and risked his life to drive them home that night. He lost the bet.” Irit’s voice dropped as she held back her tears.

“The bet with whom? God?”

“No. The devil.” She unbuttoned the last button on his shirt and started on his fly.

Ali put down the pack of cigarettes. He looked for a moment as if he was contemplating standing to pull out the bed but then thought the better of it. He was hard already beneath her fingers. But he kept talking. His excessive need to discuss balanced out her lack thereof, he’d often say to her. “Irit, do you remember what you said at the peace conference in Berlin? The Jews, the Germans and the Palestinians. We’re stuck in a triangle of pain. Maybe you didn’t realize it, but so are you—with your in-laws. You just don’t see that. What would it take for you to forgive them and let go of your pain?”

Irit put her hand on Ali’s mouth. He licked her palm. They could talk more over cigarettes. Or not, if he would let her be.

Irit rode home from work on the bike path along the ocean. The city’s bike-share system was a new addition, with electronic cards that locked and unlocked the bikes for those who were members. Elie had actually envisioned such an idea when they were in Amsterdam on their honeymoon, but he didn’t live to see it happen.

“They should do this kind of thing in Tel Aviv,” he had said. “Only the honor system would never work there.” They had both laughed, Elie’s eyes crinkling into the beginning of crow’s feet at the corners. She was 38 when they married. He was 42. Neither of them had been married before. Irit knew why she hadn’t—she was not easy to live with—but she could never figure out why Elie had not been snatched up earlier by some worthier woman. He said he’d been waiting for his angel. But she knew it was the other way around.

She locked her bike at the bike station closest to the beach where Yotam was still out in the ocean with his surfing teacher, and Irit decided to take a dip. This is why she lived in Tel Aviv. For the ocean. She stripped down to her black bra and underpants and ran into the waves. It was only May, so the water was cold. A shock to her system. Just how she liked it. When she got past the waves, to calm waters, she lay on her back and closed her eyes. Out here she could let the tears flow. Salt water into salt water. Why did her in-laws bring out the worst in her? Why couldn’t she show the same kind of compassion for them as she did for the man who pulled the trigger that killed her husband? Was it really just about guilt and blame?

When she opened her eyes, Irit saw above her an airplane doing flips and turns. An air force jet, no doubt, practicing for the Independence Day air show. It was drawing a shape in its wake. A huge triangle. Now it was coming back to the base of the triangle and doing the same thing as before, only upside down. It was a six-pointed Star of David. Of course. White against the blue sky. But it only remained that way for a few moments, as the first triangle began to fade away behind the second one.

When she and Yotam arrived home, Irit did not go into the bedroom. She called out hello and asked if her father-in-law and Muno were hungry. Muno answered that they had just eaten, so Irit fried some eggs, cut up a salad, put four slices of bread in the toaster and when they popped, set them out with cottage cheese. “Dinner’s ready!” she called to her son.

Yotam came to the kitchen-island-for-two, freshly showered and in a pair of jean shorts with no shirt. His skin was still smooth and hairless, but she knew there was little chance it would stay that way, given his genes on both sides. He looked up at her from a pair of big brown eyes, like his father’s, pushed a dark curl away from his face, and asked: “Are Grandpa and Muno joining us for dinner?”

“No. They ate already. Besides, it’s easier for Grandpa to eat in bed. It’s an ordeal to get him up. It’s just you and me, kid.” Irit lifted her arm to rustle her son’s curls. Just like Elie’s. And Ali’s. “I like it that way,” he said, taking a spoonful of yolk and bringing it to his full, pink lips. Those he got from her.

“Me too,” she lied. It was not that she didn’t appreciate the advantages of their tight mother-son intensity. But she had liked it much better when there had been three of them. Elie would sit where Yotam now sat, and Yotam would sit in his high chair between them, at the end of the island, so that they made a triangle. What was it that Elie had called them? A triangle of love. He was sentimental in that unabashed way. She loved that about him, because she would never have said such a thing, even if she thought it.

“You can go in to say goodnight to Grandpa after you finish your homework,” she added. “I’m sure he’d like that.”

Later, after dinner, after she had helped Yotam with his homework and sent him to brush his teeth and read quietly in his bed, Irit started washing dishes. She knew the right thing to do would be to go into her bedroom to check on her father-in-law and Muno, but she did not have the strength. I’ll have to go in later anyway, she told herself. She thought about what Ali had said earlier that day. What would it take for her to forgive this man? “Irit?” Startled by a voice behind her, Irit turned around. It was Muno. “I need to go now. I got tickets to Macbeth at the Cameri. The show starts in an hour. I’ll be back tomorrow. First thing in the morning.”

Irit felt her stomach tighten, her heart clench. She knew this moment was coming, yet the reality of it still seemed beyond her capabilities. She had no anniversaries to celebrate, thanks to this man she was now meant to nurse. She could not back out now, though. Cameri tickets cost a fortune. This was a huge splurge for Muno, who, she knew, sent most of his earnings back to his parents in the Philippines. “How will I know when to give him his medication? Can I leave him alone in there? I can sleep on the sofa.”

“Well, it’s best not to leave him alone, if you don’t mind sleeping next to him,” Muno apologized. “And his medication schedule is very clear. The chart’s on the night table. But if he asks for more pain killers, you can give them to him. If you want to get any sleep yourself, that is. It’s not a science. He has better nights and worse nights.”

Muno left minutes later. Within seconds, she heard a call from her bedroom: “Muno! Muno! Get back here. I need my pills!”

When he saw Irit at the threshold instead of his aide, Irit’s father-in-law’s eyes brightened. She was not expecting that. “Where’s Muno?” he asked.

“He’s off for the night. As planned. Can I help you?” she asked, noticing she still had her rubber dish-washing gloves on.

“Come closer,” he yelled “What can I do to help you?” she asked again, walking over to the bedside.

Irit’s father-in-law lifted a wrinkled hand and handed Irit a paper napkin. She took it and was about to throw it in the garbage when he barked at her again: “No! Read it!”

The napkin was crumpled in her gloved hand. She opened it up and smoothed it out. Her stomach dropped when she saw what was written in a shaky scrawl on the napkin in blue ink: “Sorry.” Was this an apology for all of the pain this man had caused her? She looked up and into her father-in-law’s pale gray eyes. They were full of tears.

“Please,” he said then. Whispered. And she followed those gray eyes to the bottle of pills at his bedside. His pain killers. “Please. No more.” He lifted a twisted, arthritic finger and pointed to the bottle.

“For the pain?” she asked him.

He nodded. “Too much pain. Always.”

“But how many?” she asked.

“No more pain. Ever. Please.”

It took a moment for Irit to understand what her father-in-law was asking of her. He reached out his trembling hand and grabbed the bottle. “Open!” he said. “That goddamned lid. You can help me. No one else can.”

Irit felt rage growing inside her throat. Why did he think she would help him? Did he intuit how much she wanted to punish him for ruining her life? Did he know how much she wanted revenge? Or did her show of undiscriminating love and compassion fool him too? Did he think she—the professional galvanizer of compassion—could be his angel of mercy?

Irit took the bottle of pills from her father-in-law and screwed off the child-proof cover, which, she now understood, was patient-proof too. The bottle was half-full of tiny white pills. How would she manage this? And as though her father-in-law had read her mind, he answered, the pain still in his voice: “In the water.”

Irit looked again into her father-in-law’s eyes. For the first time, she saw there a man in pain. Was there enough room in this bed to hold all of their pain? Even just for this one last night? He closed his lids like a nod of approval. She helped him drink the potion as she heard her heart beating in her ears. Her father-in-law reached out and took the empty bottle from her shaking hand—his was now steady—and rested the hand, with the bottle, on his chest. He closed his eyes. “Thank you,” he said and drifted off to sleep.

Irit, in a daze, went to the kitchen and finished washing the dishes. She took off her rubber gloves and threw them in the trash can. Then she brought the garbage bag out into the hallway and stuffed it down the chute. She checked on Yotam. He was fast asleep, with his book over his face. She removed the book, put it on his night table, turned off his bedside lamp and kissed his forehead. “Just you and me kid,” she said. “For better or for worse.”

Then she went to her bedroom, lay down on top of the blanket and looked up at the ceiling, waiting for sleep to come. The man beside her—his body the length of the man who truly belonged there —was still breathing, unlike him. But soon he too would be as stiff and cold as the body she had identified, shot full of bloody holes, after a night of hopeless praying and searching.

Suddenly, she felt the stone inside her chest melting, like a lava flow. Tears of all kinds—sorrow, self-pity, compassion, anger—were streaming down her cheeks and wetting her pillow. She was both the angel of mercy and the devil herself, all at once, and she would never know which one had given her the nerve to grant an enemy his final peace. She reached out for a napkin she saw lying on the blanket next to her father-in-law. “Sorry,” it said. As she wiped away her tears with the napkin, she whispered to her father-in-law, to Elie, to Ali, to Yotam. To herself: “Forgiven.”

Rabbi Haviva Ner-David is the author of two memoirs—Life on the Fringes and Chanah’s Voice—and a forthcoming book on preparing for wedding and marriage. She is a rabbinic mikveh guide and consultant at Shmaya: A Mikveh for Body, Mind and Spirit, on Kibbutz Hannaton, where she lives. She is currently in the final stages of writing a novel.