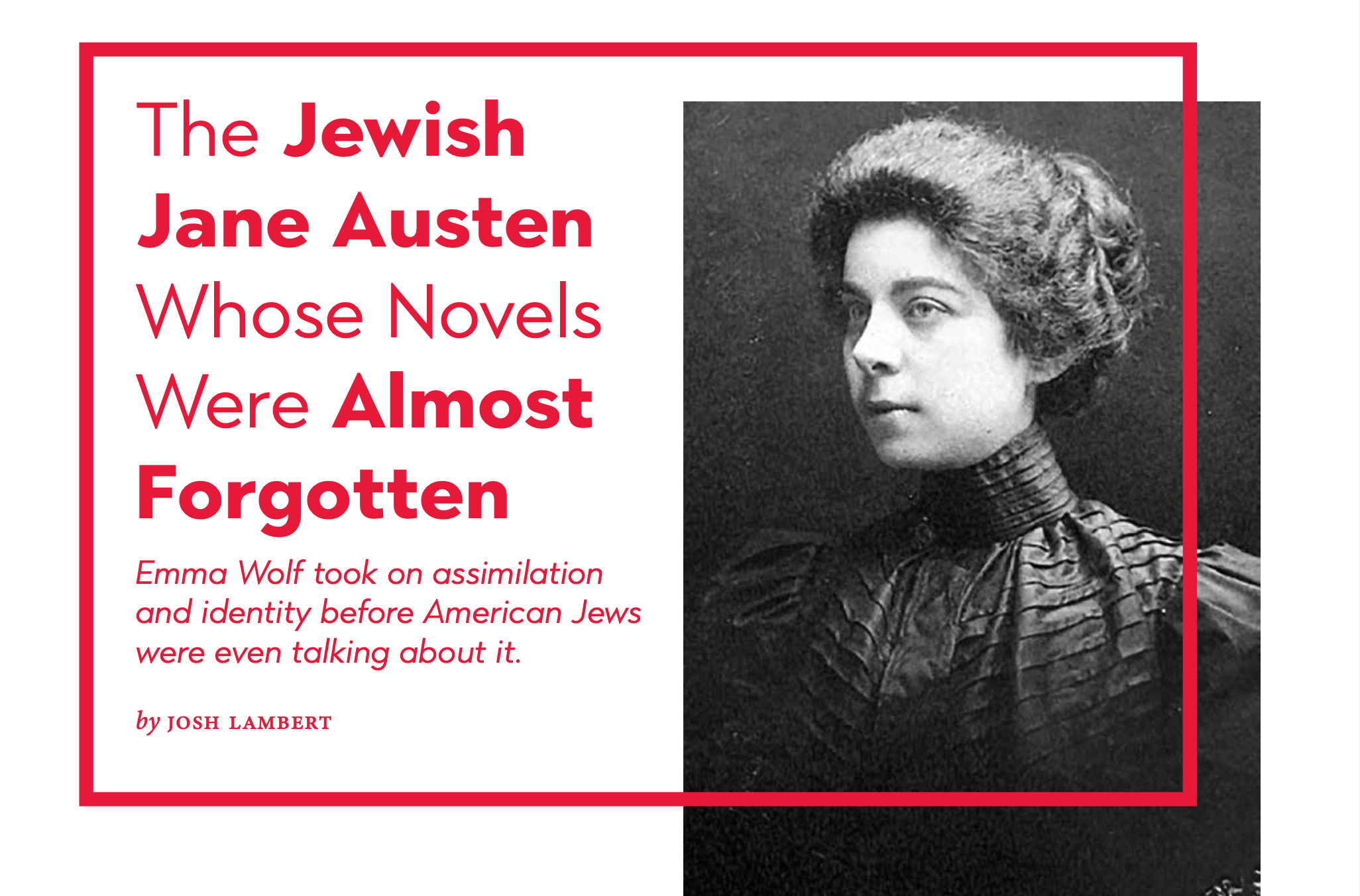

The Jewish Jane Austen Whose Novels Were Almost Forgotten

Emma Wolf was a witty, warm and acclaimed novelist-of-manners who wrote at the dawn of the twentieth century. She was also almost lost to history. Even after feminist scholars began in the 1970s to recover the neglected work of women writers, Wolf wasn’t reprinted and reevaluated like Anzia Yezierska or Zora Neale Hurston. As late as 1992, Barbara Cantalupo, a literary scholar of 19th-century American literature who wrote about Edgar Allen Poe and Herman Melville, had never even come across Wolf ’s name.

Cantalupo and her collaborator Lori Harrison-Kahan told Lilith that Wolf didn’t appeal to revisionist feminist and ethnic studies scholars in the 1970s and 1980s because her views on class and gender weren’t “radical,” “her work isn’t fervently feminist,” and because her characters aren’t Jewish in a way that fits neat Jewish Studies narratives. They’re not immigrants on the Lower East Side. Instead, they’re middle-class, highly cultured Californians, and they “sprinkle their speech with French phrases more often than Yiddish ones.”

While that disqualified Wolf from the earlier revision of the canon, it’s also what makes her so vital now. Wolf ’s novels contradict stereotypes about Jewish women at the dawn of the 20th century and offer insights into one of the most fascinating, progressive Jewish communities of that era.

Her 1900 novel, Heirs of Yesterday, which Cantalupo and Harrison-Kahan have just brought back into print, is not just a skillful novel of the American fin de siècle, but a book that reveals its author as stunningly prescient and bravely committed to telling the truth about American Jews’ experiences.

Wolf was born in San Francisco in 1865, to Jewish parents who had emigrated from Alsace-Lorraine. Her father, who owned stores in half a dozen California gold rush towns, died suddenly when she was 13, while her mother was pregnant with the couple’s eleventh child. Wolf ’s family attended a landmark Reform synagogue, Emanu-El, but her friend Rebekah Bettelheim later remembered that during high school she and Wolf began to “doubt the worthwhileness of all the sacrifices” Judaism required of them. “Why make a stand for separate Jewish ideals? Why not choose the easier way and be like all the rest?” Why not just assimilate?

Wolf eventually took up that question in her fiction. Her first novel, Other Things Being Equal (1892), explores intermarriage between a Jewish woman and a non-Jewish man, and wonders whether it might actually be a salutary development for America’s Jews. (Wolf’s own sisters married non-Jewish men.) Having succeeded with that, in Heirs of Yesterday, she presents a young man, Philip May, who has chosen what Bettelheim referred to as “the easier way.”

When the novel opens, Philip has just returned, after years of study and training at Harvard and in Europe, to his hometown, San Francisco, to set up a medical practice. Philip’s father, a Jewish immigrant, speaks in an accent and intersperses his comments with Yiddish (as well as French), but Philip considers himself a “scion of cultured modernity.” In other words, he notes that “beyond the blood I was born with, pretty nearly all the Jew has been knocked out of me.” Passing as a gentile among his classmates and colleagues has come naturally to him—he notes that his name and physical features “[tell] no tales”—and he’s chosen to pass, both for the sake of his social and professional advancement and because he simply doesn’t feel connected to Old-World Judaism and what he regards as its constraints, stric- tures, and disadvantages. “What have I to do with ghettoes?” he asks, defiantly. “What [have I] to do with Jewry?”

To emphasize that Philip’s choice isn’t inevitable, Wolf presents another character who suggests an alternative: a sophisticated, modern Jewish woman, Jean Willard, like Philip, is the child of Jewish immigrants, but she’s not parochial or ghetto-minded. She’s disinterested in Hebrew (“There are so many more useful and ornamental things to learn,” she muses), and we’re told, “her religion had always lain lightly upon her.” She reports that she couldn’t even list the Ten Commandments. Still, she values the bits of Jewish tradition she does know, see- ing herself as ineluctably a part of, and a believer in, the Jewish people: “Every one of us carries the blood, the history of all of us in his veins, no matter how different we may appear.”

As Cantalupo and Harrison-Kahan point out, Philip and Jean embody San Francisco’s Gilded Age Jewish community, during which a remarkable number of Jews, many of them like Wolf descended from Alsatian immigrants, attained financial success and practiced a progressive religion. San Francisco elected Jews to political office as early as 1856, and the city even had a Jewish mayor, Adolph Sutro, in the late 1890s. Its leading Reform synagogue, Temple Emanu-El, hired a female cantor in the 1880s. This unusual community nurtured Wolf, and the possibilities that Philip and Jean consider—a complete shucking off of one’s Jewishness, or an insistence that it continues to have salience—confronted her and the other middle-class, intelligent, cultured Reform Jewish women and men of that particular time and place.

To her credit, Wolf does not paint either of these paths flatteringly. Philip’s expectation that he will be accepted by the highest echelons of gentile society seems, in his 1890s context, audacious, or simply naïve. The novel acknowledges the overt antisemitism that suffused American life at the time, with the most popular humor magazines, “Puck and other witty periodicals” (like Judge and Life), regularly publishing brutally hateful caricatures of Jews (as well as of African-Americans and other marginalized groups). Poor Jewish immigrants were sneered at and feared as criminals and degenerates. Even the wealthy social gentility to which Philip aspires traffics in anti-Semitic comments, and its members do so even when they’re trying to be charming. To wit, a debonair non-Jewish painter, dazzled by Jean’s beauty, reacts with a highly double-edged remark when she reminds him that she’s Jewish: “Your sex unsects you.”

But if non-Jewish socialites come off poorly in Wolf ’s novel, so, too, do the well-heeled Jews. A representative of that com- munity, with a “prosperous-looking, lazy figure and stout, florid face,” from whom “good nature seemed” to exude, explains, with great self-satisfaction:

“Look at me. Look at my wife—look at my children. We’ve as good as the country affords. Who has a finer home—who’s better dressed, better fed, hey? My son will have all the education he’s

fit for and my daughter all the accomplishments going—if she wants ‘em. We help support the theaters and operas, and help liberally, by Jove! We travel, enjoy our money and ourselves— and let others enjoy our money as well.”

Rather than magnanimous, this allrightnik comes off as a blowhard. Even as she presents them boasting about their cultural sophistication, Wolf cannily includes the pleasure these Jews take in racist coon-songs—the wildly popular but vulgar and hateful pop culture of that era. Like any group, the San Francisco Jewish community depicted in Heirs of Yesterday has its more and less appealing members, but Wolf presents Philip’s resistance to joining a Jewish men’s club and taking his place in this community as understandable, not the effect of self-hatred.

In fact, because she understands that neither gentile high society nor the Jewish bourgeoisie can offer what Philip (or Jean) seek, Wolf provides them with a conflict that is real, affecting, and still relevant. As many diaspora Ashkenazi Jews discovered in the traumatic century that followed the publication of Heirs of Yesterday, one’s distaste for Jewish parochialism does not make assimilation into the bigoted mainstream more palatable. Nor does one’s recognition of the antisemitism in universalist move- ments make a Jewish ghetto more enticing.

That bitter realization motivates much of 20th-century Jewish literature; perhaps nowhere is it expressed with more sharpness and anguish than in Yankev Glatshteyn’s 1938 poem, “A gute nakht, velt” (“Good night, world”), in which the speaker turns away from the “wide,” “stinking” world with its “flabby democracy” and “guzzling and gorging,” its false “liberators,” those “Jesusmarxes,” instead choosing to “return to the ghetto,” clear-eyed that all it offers is the opportunity to “grovel in [the] dirt” and “roll in [the] dust” of “Gloomy Jewish life.”

While expressing the situation more gently and warmly than Glatshteyn, Wolf dazzles in her perspicacity. Because of her extraordinary experience growing up in a wealthy, progressive American Jewish community, she was able to put her finger, much earlier than other American Jewish writers could, on a signal conflict of modern Jewish life.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the novel’s history, detailed by Cantalupo and Harrison-Kahan in their excellent introduction to the new edition, is that it was rejected by the Jewish Publication Society, the leading American Jewish publishing house of its day.

A majority of JPS’s committee felt, in the scholars’ summary, that the novel “would stoke … divisiveness rather than bring American Jews together through common culture and tradition.” Wolf ’s novel was eventually published by A. C. McClurg, a nonsectarian Chicago publisher that had published Wolf’s first novel and would go on to publish W. E. B. DuBois’ classic The Souls of Black Folk a few years later, as well as Edith Eaton/ Sui Sin Far’s Mrs. Spring Fragrance, a pioneering work of Asian-American fiction.

In other words, Wolf had better luck with a non-Jewish publisher that understood there was an enthusiastic reading public for stories of immigrants and marginalized groups than she did with a firm that was committed to addressing a Jewish readership. This isn’t too surprising, given the track record of Jewish publishers, not to mention the short-sighted rabbis whose sermons railed against Philip Roth’s stories in the 1950s and 1960s. That resistance even echoes today. I’ve heard it when I judge Jewish book prizes: why, funders sometimes ask, can’t our authors focus on how wonderful Jewishness can be?

Wolf, long before Roth, knew why—you show you care by being honest. “Truth-telling should be an author’s religion,” she wrote, the year after Heirs of Yesterday was published, to reviews both celebratory and scandalized. “All that I have written has been said in the spirit of love—the love that has the courage to point out a fault in its object.”

When Heirs of Yesterday was first published in 1900, the majority of American Jews weren’t in a position to appreciate Wolf’s insights. Most were poor and too focused on earning a living to worry about high society antisemitism. Many of them, recent arrivals, couldn’t have even read a novel in Wolf ’s decorous, witty English prose anyhow. They probably couldn’t have imagined, either, the degree to which their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren would share more with Wolf than with themselves.

Cantalupo and Harrison-Kahan expect, first and foremost, that “readers who enjoy writers like Jane Austen and Edith Wharton will similarly take pleasure in Wolf ’s novels,” and Wolf ’s work absolutely does deserve a more prominent placement in the annals of American literature. Because many American Jews today resemble the ones in Wolf ’s San Francisco more than their ancestors could have imagined, one can hope that Heirs of Yesterday might resonate, too, with a surprising contemporaneity.

Josh Lambert is the Sophia Moses Robison Associate Professor of Jewish Studies and English, and director of the Jewish Studies Program at Wellesley College.