Lilith Feature

Recreational DNA Testing & Its Uninvited Consequences

This past season, thousands received gifts of DNA testing kits from services like Ancestry.com and 23andme. Tens of millions of these kits have been sold, and their DNA results logged in to massive databases, creating an exponentially expanding web of genetic information.

For some people, personal or family history has been obscured by intertwined forces of persecution, migration, genocide and loss, sometimes followed by assimilation or just losing track of our relatives. So people buy the kits both to answer unresolved questions about origins and to get a greater sense of belonging. they may get more than they bargained for—upending their lives and sense of self, even completely reconfiguring families.

The kits are enabling dramatic revelations, even as they add pop-up warnings when offering to connect people to unknown biological relatives. Take a look at recent headlines that repeat the words “shocking” and “bombshell” over and over again: “With genetic testing, I gave my parents the gift of divorce,” was one in Vox, written by a biologist who discovered a hidden half-brother. “23andMe revealed that my daughter is not mine,” a letter-writer told a financial advice columnist. “My ancestry test revealed a genetic bombshell,” one article in NYPost declared. “I took a DNA test and unlocked a family bombshell, completely by accident,” is the subhead for an essay by an ABC news correspondent who located two brothers for his adopted dad.

Yes, people are reuniting with birth families, long-lost cousins, adopted siblings—but they are also discovering less savory things, and they are not prepared. “The era of family secrets is over,” science journalist Libby Copeland told Lilith (see sidebar).

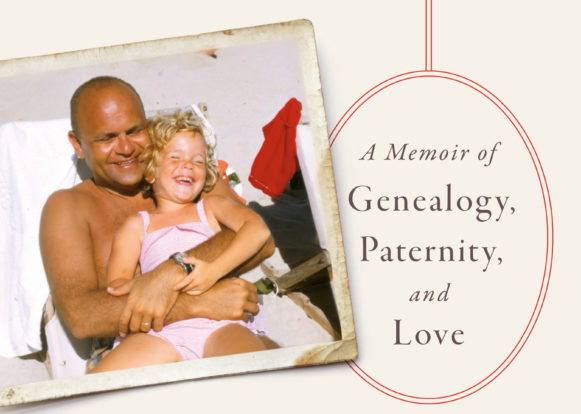

Writer Dani Shapiro, who has vividly chronicled her complex relationship with her Orthodox Jewish family, is one such person. Recreational DNA testing threw her life into turmoil. At first, when the tests she’d gotten on a whim came back, she wasn’t concerned by her unusual results. “I say puzzled—a gentle word—because this is how it felt to me,” she wrote in her 2019 memoir, Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love.

Ancestry told Shapiro that she was only about half Ashkenazi, and the rest of her makeup was a European mishmash. She was unfazed, considering it just a bit “odd.” Only later, when Shapiro used Ancestry’s tools to compare her genes directly to those of her half-sister Susie, did she realize something shocking: she and her sister aren’t biologically related. At all.

Blonde since childhood, Shapiro had fielded her share of comments her entire life about not being Jewish-looking, even being told she would have been useful under Nazi rule as someone who passed as Aryan. Suddenly, as she began to unravel the results, the lightning bolt hit. “It had taken 0.04538 seconds—a fraction of a second—to upend my life,” Shapiro wrote.

Inheritance takes a deep journey through Shapiro’s sleuthing about herself, and her family, and the history of assisted reproduction. Her discovery enabled her to understand the truth at last about the man she had loved, lost in a car accident, written about and for, and considered her father: he wasn’t, at least not biologically. “It wasn’t so much my future that was being irrevocably altered by this discovery—it was my past,” she wrote later in the book.

Another woman whose life was upended by digital gene sleuthing was Alice Collins Plebuch, whose interest in data, and in learning about her dad’s heritage—he was raised in an orphanage—fueled her desire to test. Journalist Libby Copeland reported on Plebuch’s story in a long piece in the Washington Post, and the story began like Shapiro’s: she found out, unexpectedly, that she was about half Jewish. This revelation unnerved her, especially when some digging revealed that her proudly Irish family were not secret converts from Judaism anywhere in the history she could find.

Just as Dani Shapiro kept investigating her own results by comparing her genomes to the DNA of family members, so did Alice Plebuch; it turned out, painfully, that her cousins were not her genetic cousins—just as Shapiro’s sister was not her biological sister. A long, painstaking (and emotionally draining) search, with many relatives helping, led her all the way up to some twist of fate in the hospital the day her father was born: something had happened there. Something had switched.

But dead ends ensued after this. Then, one day, a new “genetic match” on one of Plebuch’s non-DNA-linked cousins led them to a woman who had always thought she was 100% Jewish. But she completed an ancestry kit, and it told her she was half Irish. Her father was born in the same Bronx hospital as Plebuch’s. Together, these two women received one of the most shocking answers you can imagine, worthy of a soap opera.

Alice’s story—a personal detective story with implications for all of us—forms the backbone of Copeland’s forthcoming book, The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Uncovering Secrets, Reuniting Relatives and Upending Who We Are, a read which explains the genetic science, and the stories, behind the phenomenon. Because it is a phenomenon. And for families that decide to test their genes recreationally, strange results are only a piece of the puzzle: “Genetic testing gives you the what, but not the why,” Copeland wrote in her initial Washington Post article about Alice.

In other words, for every odd-seeming set of genetic results, there may necessarily be a secondary level of sleuthing that can reveal uncomfortable truths, tear down family legends, and help find long-sought answers. Dani Shapiro describes this phenomenon of unexpected test results as a “tidal wave” and an “epidemic.” On book tour, Sharpio told the Guardian, “In every audience, there is a significant number of people who have discovered family secrets of their own: adoptees who were never told; donor-conceived people who never knew… older men—not my usual kind of reader—who have been anonymous donors…”

Copeland, who has continued to seek out and amplify DNA discovery stories on social media, agrees, telling Lilith that this technology is changing the social fabric, rapidly. In her initial piece about Collins, she wrote. “The same technology can cleave families apart or knit them together…it can bring distantly related members of the human family together on a quest, connecting first cousins who look like sisters, and solving a century-old mystery that could have been solved no other way.”

Even as people continue to take advantage of seasonal sales to gift these kits, the number of warnings about them is growing. “Why DNA testing kits shouldn’t be on your holiday shopping list,” one December article on the website Qz implored, reminding readers that the companies, even those who have vowed to respect privacy, can renege in the future. The Pentagon has taken the step of urging military personnel not to take these DNA tests for fear of surrendering data that could be used against them.

But even if a consumer resists such kits, it may be too late. “Even if you don’t choose to test, you are actively opted in by the fact that someone else within your circle of relatives probably already has,” Copeland told Lilith. As Shapiro told the Guardian about her unusual book tour audience: “Science is going to force us into a place where there can’t be these secrets. But right now, we’re dealing with a tidal wave.”

In This Feature

an interview with Libby Copeland

The Era of Family Secrets Is OverAn interview with Libby Copeland suggests that this means the end of family secrets.

admin

A Change, Inked: Dani Shapiro Reckons With a DNA Discovery“Last spring I found out that my father was not my biological father,” I told him, keeping the story as brief as possible.