My Scarlet Summer

A six-story building on Tiebout Avenue in the Fordham section of the Bronx. Inside apartment 3C live five inhabitants, then four, then three. A bipolar father in a manic state being thrown out by my mother. We are four. Me shrugging (What could I say?) when an elderly neighbor calls me aside to ramble, “Your mother has no heart. Where’s that man to go?” And the mother with no heart vacillating between screaming rages at us, her two daughters, and quiet retreat. Sometimes she says it aloud (You lousy kids have trapped me in this life), but there is no need for her to do so. We already know.

Our beloved grandmother bakes apple pies and helps us with school projects. Her bedroom is filled with books she encourages me to read. The stabilizer of the house is now withering away in the bedroom next to the one I share with my sister. The word cancer is never spoken. Soon we are three.

A week after my grandmother dies, we are awake all night preparing our migration to the “promised land” of Co-op City, a middle-income housing development plopped down where the amusement park Freedomland once stood in the Northeast Bronx. Moving men arrive hours early, a second afternoon job unexpectedly squeezed into their day. They find three sleep-deprived and disoriented figures frantically throwing items into cartons, nowhere near done. These burly men, hired only to move boxes, start folding clothes and packing linens. The only home I have ever known is soon no more.

After the move, I sometimes board a city bus alone to travel across the Bronx to gaze at that old building on Tiebout Avenue, imagining we are all still living there. My mother’s mood swings worsen, and my sister withdraws. Weekly visits with my father eventually morph into a lifetime of care provided him by us, his daughters. For now, I shop, cook, clean and do laundry, hustling to get it done and finish my homework before my mother arrives home from her long commute. I never know what to expect when she walks in the door, but I know what she expects: the table set and dinner cooked.

That is the backdrop for the summer to come. I eagerly anticipate the first day that the familiar yellow school bus will pick me up on its way to a day camp nearly an hour’s drive away. A group of friends return year after year, with new additions happily mixing in. In the days before Facebook, we reconnect quickly. Camp is my oasis from chaos; it’s a place I cherish.

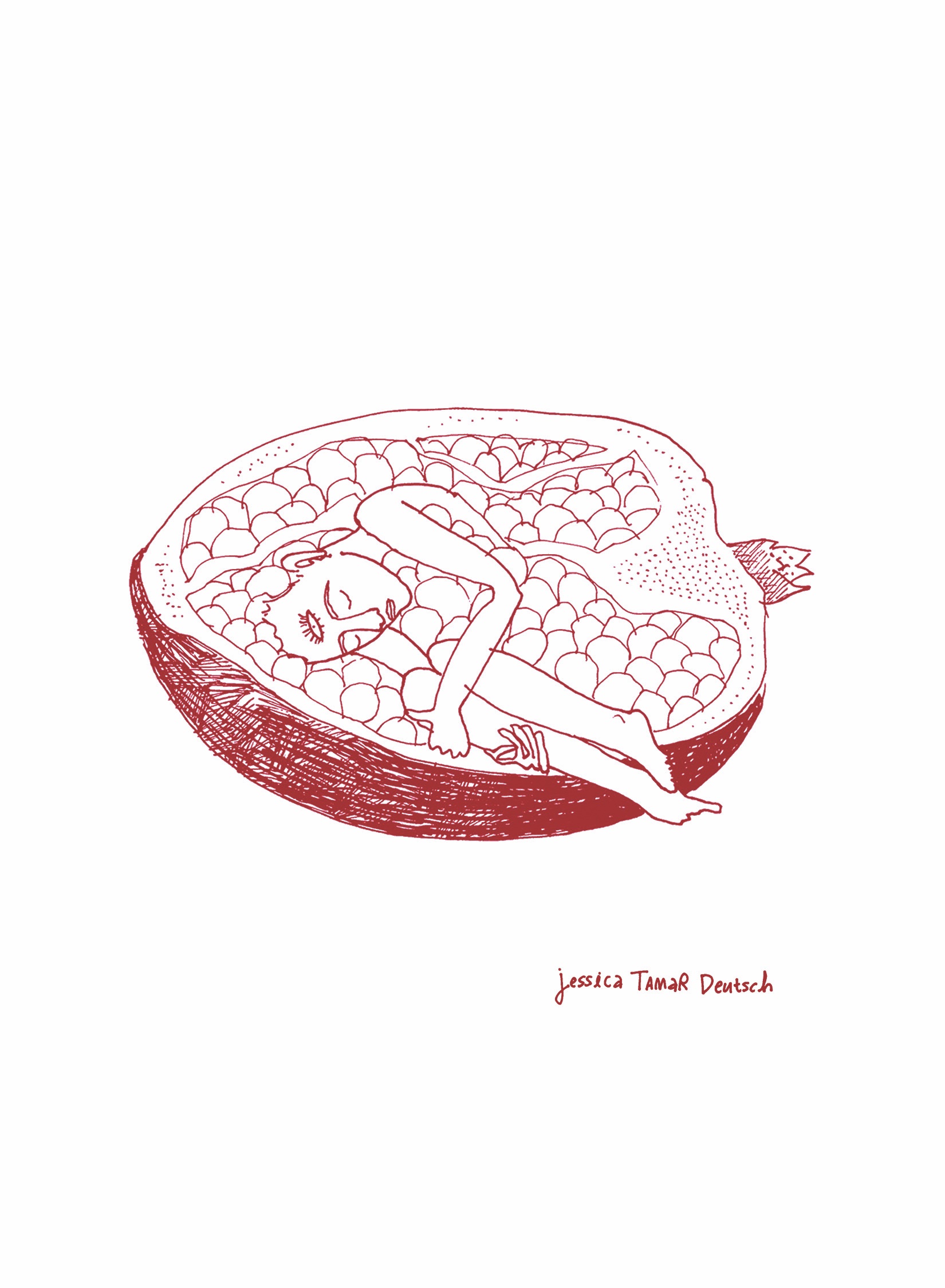

Only…this summer, change continues its unrelenting course. Having aged out of camp, my sister leaves me to board the bus alone. My childhood friend Darlene has also moved to Co-op City and inexplicably transforms into something I am no match for. It is her first summer at camp, my camp, and she will walk on the bus like she owns it. Her swagger unmistakable, with me her target. Even now, I am surprised by how quickly Darlene turns longtime camp friends into a gaggle of mean girls. Back then, I have no idea what to make of it, less what to say. I retreat into myriad books and the piles of Reader’s Digests that once lined my grandmother’s bookcase. As Darlene takes up more space, I feel myself shrinking. A solitary 12-year old whose first period chooses this summer to appear.

At first, a trickle. A red spot on my underpants prompting my mother to hand me a pamphlet about menstrual cycles which I try reading but find incomprehensible. Then the flow really gets started. Day after day, the entirety of my summer is filtered down to a backpack filled with piles of sanitary napkins and three changes of clothing—all of which I need. I do not remember one adult present enough to question this flow, or take me to a doctor.

The first day of camp. I awaken before the alarm tells me to, the heaviness of the year sliding away. Prepare the camp bag. Check. Pack lunch. Check. Bathing suit and towel. Check. Check. So exciting, such anticipation. I head downstairs way earlier than needed. A glorious sunny day. An empty bus arrives and I care not that I will have the longest commute. Stop after stop, kids piling in. Hello! Hello! So many familiar faces. And then Michael. In one year he has grown a foot taller, with braces replaced by perfectly straight and oh-so-white teeth. His awkwardness seems to melt away over the cold winter. Darlene boards close behind, her smooth skin exposed between a midriff blouse and low-cut denim shorts. Looking in my direction, she confides something and they laugh. It happens quickly and I immediately understand. That sinking feeling hits even before my friend Michael stares uncomfortably back at my greeting, seating himself rows away. Darlene takes her place nearby. She is glowing. The summer games begin.

Months before this, I play a board game in Darlene’s bedroom on Tiebout Avenue. Holding dice in hand, she breathlessly confides that her mother slapped her; Darlene had just gotten her first period. The news slowly sinks in. Slaps are common for us kids, only this seems different. My mother later dismisses the act as an old Jewish tradition we would never practice. Puzzling, since it is the only religious observance I have ever seen from Darlene’s family. Equally puzzling, we are Jewish but my mother is suddenly averse to slapping. I try to sound excited but cannot find the words. We will be leaving Tiebout Avenue soon and change is swirling all around me. I do not need any more of it from my little playmate. I focus on the game board, feeling Darlene move on.

Each day, I trudge to the last row on that school bus. Empty there and remaining so. I try to ignore Darlene and the campmates encircling her. Ironically, I am reading Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter that summer. The Scarlet Letter soon finished, another book replaces it. I read anything I can find, crawling deeply into each story to forget temporarily where I am, who I am. I cannot imagine the willpower it took to step out of that apartment each day, house key dangling from my neck, and ride the elevator down 21 floors to saunter outside and wait, silently. Such is a childhood where obedience is demanded and explanations withheld. I bleed for seven weeks straight and nobody seems to notice. Even a slap on the face would be preferable to this.

The bus arrives at camp with a jolt. I feel abdominal cramping and am nauseous. I tie a sweatshirt around my waist, in case my front line of protection fails me. “Cover up” becomes my silent mantra. I head straight to the camp cabin, rushing to the bathroom. Change this, change that. Under the watchful eyes of my campmates, I quietly tell the surprised twentysomething counselor that, yes, I still have my period. Excused from swimming, from sports, from just about everything, I escape into reading until time for lunch. Occasionally I feel better and join a volleyball or kickball game. Mostly I sit with my books wishing for an end to this seemingly endless summer.

Of course, the summer does eventually grind to a stop. During its long stay, something inside me changes, and I know it. The emotion feels close to anger, but not exactly. Like a turtle, I stuff everything deemed unsightly inside a hardening shell. Sanitary napkins, a manic parent, and grief are high on the “no share” list. I practice smiling in the bathroom mirror until it becomes routine. In short time, I remake myself into a popular middle school and then high school student. Much later, I understand the price one pays for carrying this stuff around; at that moment, on the cusp of my new life as a teenager, I would have happily accepted any trade-off.

Karen Bloom is a New York-based writer and a founding partner of Fund Up, a fundraising consulting company.