Art, Disability and Family

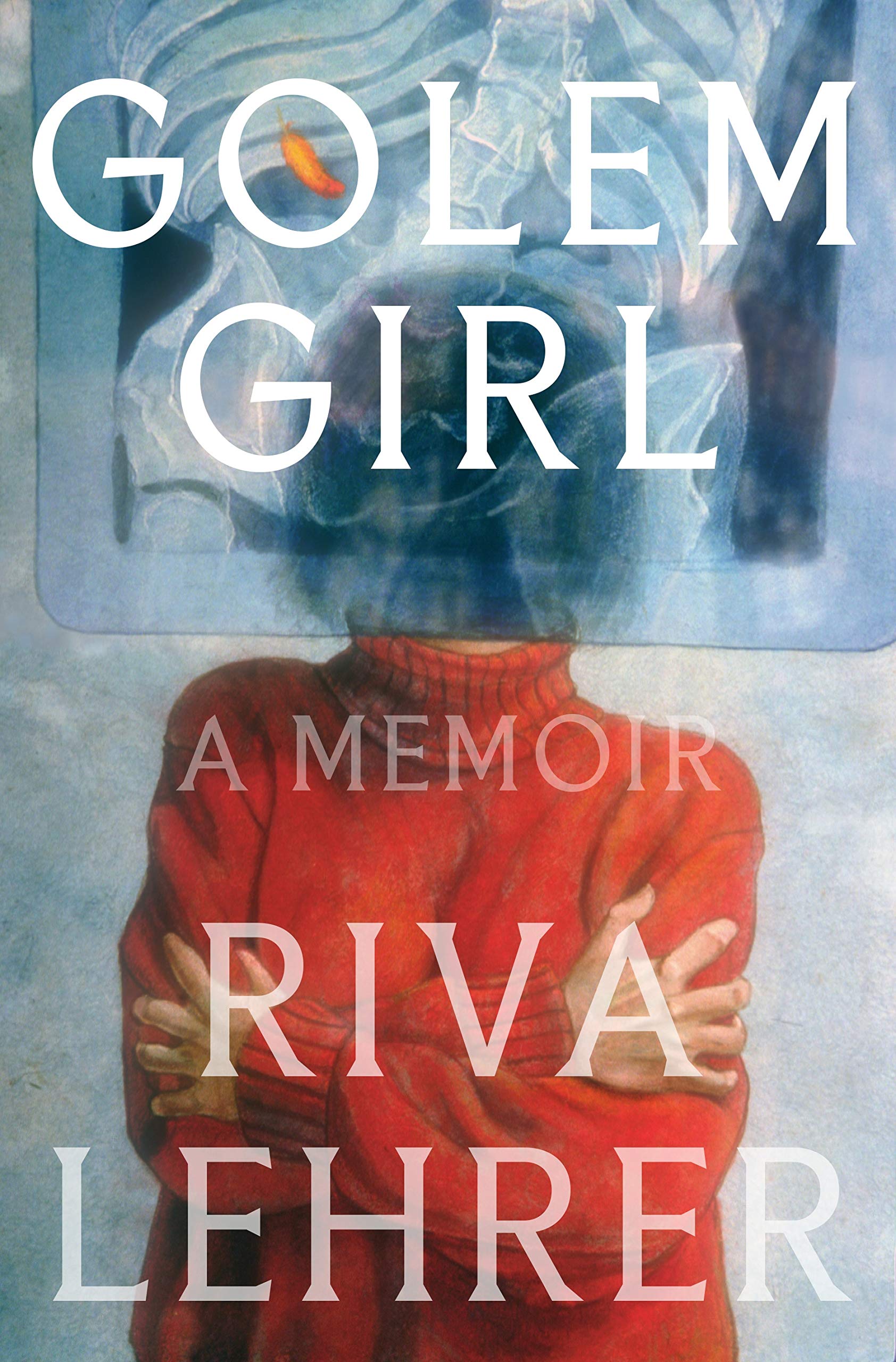

I can promise you one thing: when you read this book, you will fall in love with Riva Lehrer. She’s funny and creative and insouciant and so smart that her personality leaps right off the page. It’s rare for me to sit down with a memoir and then just…not get up. But that’s what happened with Golem Girl: I started reading and didn’t stop until it ended.

Lehrer was born in Cincinnati with spina bifida, and in another context and another time, she might not have made it past infancy, or indeed might not have been allowed to. But Lehrer had a secret superpower: her extraordinary mother, Carole, who made damn sure that little Riva would come home. Still, for kids who spend their infancies in hospitals, home, as Lehrer gently lets us know, is complicated. Our bodies and our relationships to our bodies are, for many of us, a huge part of what it means to be home. But if that very body is itself always seen as wrong, is inadequate, is itself a monstrous and fear-inducing entity, and is always being reimagined, revisited, reframed—quite literally in the case of someone who is ever in surgery or just out of it—home can be hard to find.

Hard, but not impossible. This is a book about disability and Disability (one is a way of being in a body, the other is culture, community, politics, and advocacy), and the absolutely vital role that Lehrer has played in showcasing and celebrating people in all their difference, as a Chicago-based artist and curator.

Golem Girl [Penguin Random House; $30] is lot of different things, of course: a memoir, a precious glimpse into the life of an artist, a study of creativity, of difference and disability and art and life and queer- ness. It’s a book about family and feminism and motherless daughters and anger and hope and love. It’s a book (and this is important) about the ethics of relation- ships: between family members, between friends, between lovers, and, powerfully, between artists and those they represent.

What this book is not—quietly and firmly and absolutely not—is a book about medicine, as Lehrer makes clear in a small note on page 276. She is careful to critique doctors (and she has reason to, even as she also pays them respect) but not to critique medicine itself. That would center it too much: it’s a book that includes medicine but will not be dictated by it.

But even as it is all these other things and more, this is a Jewish book. Which means that it’s caustic and funny and full of insider baseball. Lehrer drops Yiddishisms freely and with abandon, and with considerably less explanation that she affords technical terms in art, or surgical practice, or shoes. Because the Yiddishisms (and some Hebrew terms, but actually she translates those) are not foreign for Lehrer. Yiddish is not, for Lehrer, a foreign language. It is not italicized.

In this gorgeously illustrated volume, Riva Lehrer collaborates with her portrait subjects, a central part of her ethical practice for all representations. It comes, of course, from her own childhood sense of herself as Golem, as a non-autonomous monster. Her work is a sharing of autonomy, giving her subjects the opportunity to voice how they want to be seen and represented. And her book is another part of that autonomy, narrating her own experience.

But that same book is also a collaboration with the reader, whom she invites into her life, her world, and—generously and profoundly, as much as it is possible—into her mind and body. And once there, you, like me, won’t want to leave.