Danger and Opportunity in the Esther Narrative

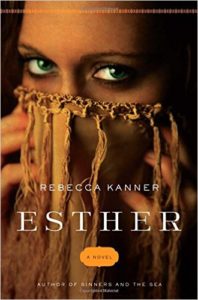

A young Jewish girl is ripped from her hut by the king’s brutish warriors and forced to march across blistering, scorched earth to the capitol city. Trapped for months in the splendid cage of the royal palace, she must avoid the ire of the king’s many concubines and eunuchs all while preparing for her one night with the monarch. Soon the fated night arrives, and she does everything in her power to captivate the king and become his queen. Her name is Esther, and Rebecca Kanner has brought her memorably to life in this retelling of the Biblical story, Esther: A Novel (Howard Books, $15.99).

A young Jewish girl is ripped from her hut by the king’s brutish warriors and forced to march across blistering, scorched earth to the capitol city. Trapped for months in the splendid cage of the royal palace, she must avoid the ire of the king’s many concubines and eunuchs all while preparing for her one night with the monarch. Soon the fated night arrives, and she does everything in her power to captivate the king and become his queen. Her name is Esther, and Rebecca Kanner has brought her memorably to life in this retelling of the Biblical story, Esther: A Novel (Howard Books, $15.99).

Kanner’s Esther learns that wearing the crown brings with it a fresh set of dangers. When a ruthless man plies the king’s ear with whispers of genocide, it is up to the young queen to prevent the extermination of the Jews. She must find the strength to violate the king’s law, risk her life, and save her people. What did Kanner do to make the ancient text feel new again?

Rebecca Kanner: I was intrigued by the feat that Esther carried off — saving her people. I retold the story so that beauty and obedience weren’t her most important characteristics. I was inspired by looking at paintings of Anne Boleyn and reading descriptions of Cleopatra (as well as looking at pictures of the coins that feature her). While these women are widely believed to have been gorgeous, they were not actually pictures of traditional physical perfection. Their personalities, including both wit and charm, are what I believe accounted for much of their attractiveness. We have continued to mythologize their beauty as an explanation for their success (however short-lived it was for Anne Boleyn), instead of focusing on their intellects.

Yona Zeldis McDonough: You bring the reader a lot of history beyond the Book of Esther we know from the Bible.

R.K.: I wanted to merge the Book of Esther with the history of Persia. I used various sources including Persia and the Bible by Edwin M. Yamauchi; The Royal City of Susa, put out by The Metropolitan Museum of Art; and my favorite, Herodotus’s The Histories. But sometimes the best way to figure out what research you need to do is to start writing.

Y.Z.M.: Esther comes very much alive, since we hear her own voice, first person.

R.K.: I originally wrote Esther in the third person. Then I realized that I’d made her somewhat annoying! When you start a sentence with “I” it’s harder to follow it with something that paints the character in a negative light. Esther is 14 when the story begins, and in trying to portray her youth and inexperience, I’d made her a little too temperamental. It’s nice to leave a character a lot of room for growth at the beginning of a novel, but not if she ends up turning off readers.

Y.Z.M.: In your previous novel, Sinners and the Sea, you adopt the voice of Noah’s wife. This has been a theme that has pulled other novelists; for example, the book Noah’s Wife by T.K. Thorne. Tell us more about what drew you to this character.

R.K.: I attended Talmud Torah day school as a child. The women of Genesis were very present for me, especially Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah, because my teachers added them to the Amidah prayer each morning. I got to begin each day with these women. They were the teachers and friends of my youth.

As an adult I was surprised to find that I couldn’t remember any details about Noah’s wife. I went back and read the story of the flood, and saw that she was mentioned only in passing, never even named. Without a name, it’s hard to talk about her, or even to think about her. I wanted to bring her to life. If she raised her family amongst sinners and brought them through the flood to the new world, she performed a great task and surely had a story to tell.

Identity naturally became a theme in the novel. When my novel begins, she actually doesn’t have a name. She is able to be identified only by her relationships to other people — wife, mother. There is a point in the novel where she asks Noah for a name, and he tells her he’s already given her one: “Wife.” Later, when they’re on the ark and she considers the possibility that Noah and her sons might die, she wonders: If they die, who will I be?

I came to this question and the other questions I raised in the novel with a Jewish sensibility, one of inquiry and exploration. The narrator wrestles with questions of whether God is watching over her or not, and whether this God is benevolent or wrathful. Some Christian fundamentalists are upset by these questions, as you can see by looking at the reviews or taking a peek at my hate mail.

Yona Zeldis McDonough is Lilith’s Fiction Editor and the author of seven novels. Her most recent, The House on Primrose Pond, came out from New American Library in February, 2016.