Barbra Streisand Was My Rabbi

My Polski family didn’t celebrate Christmas like other families. While December 25 was the big day for everybody else, my father insisted on sticking to Old Country ways.

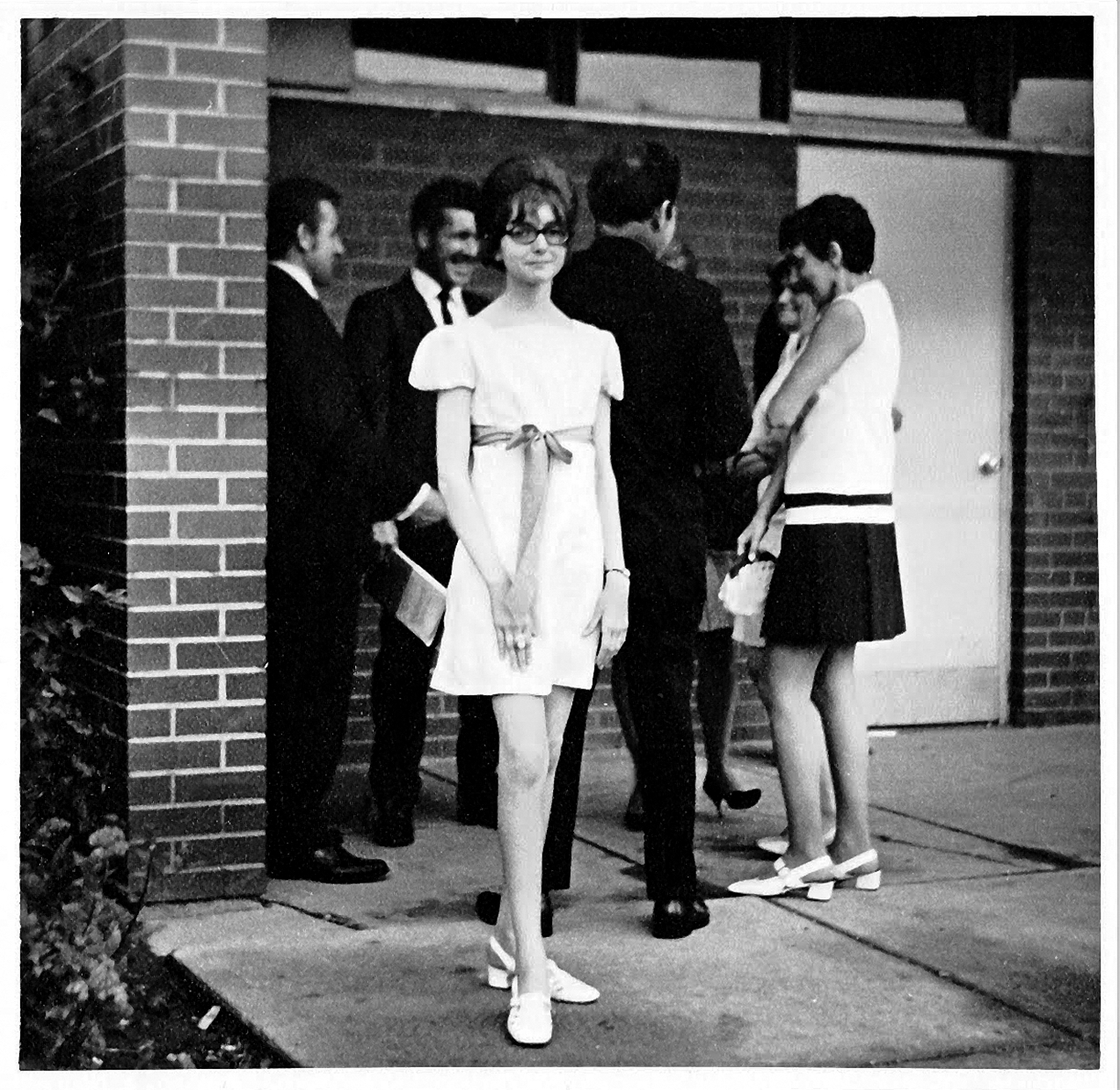

In LagowskiLand, we celebrated on Wigilia, or Christmas Eve. With the appearance of the first evening star, three funny Lagowskis gathered around the dining room table. My mother, Joanna, with her chin-length dark bob and quick brown eyes, wearing her best beige blouse and skirt; my father, Andrew, with his wispy blonde pate, twinkling blue eyes, sporting a smart ascot at his white shirt and freshly pressed grey trousers; and me, Krystyna, with my drab hair and thick glasses, in my latest velvet frock.

First, we shared an oplatek, a communion-like wafer imprinted with a Nativity scene, bestowing good wishes upon each for the year ahead. My mother had spent days preparing 12 meatless courses (one for each Apostle), including fragrant barszcz (beet soup) with plump mushroom uszka (dumplings), tart herring with apples, cod with spicy tomato sauce and vegetables, trout in gelatin with eye-watering horseradish, and as much dessert as we could bear.

One year, my mother made curious little fish balls that she called gefilte fish. We had them with glazed carrots and sliced beets. They were quite tasty.

After dinner, it was time to open gifts. Occasionally we found the strength to drag ourselves to midnight mass, and stagger back to LagowskiLand.

On Christmas Day, the Lagowskis would go see a movie, usually a musical or a light comedy. In 1968, my mother decided we should see “Funny Girl.” My father and I wanted to see “2001: A Space Odyssey.” But my mother insisted, and we caved.

We planted ourselves in the plush red velour seats in the elegant University Theatre on Bloor Street, Toronto’s most fashionable address. And something happened, there in the dark, on December 25, 1968.

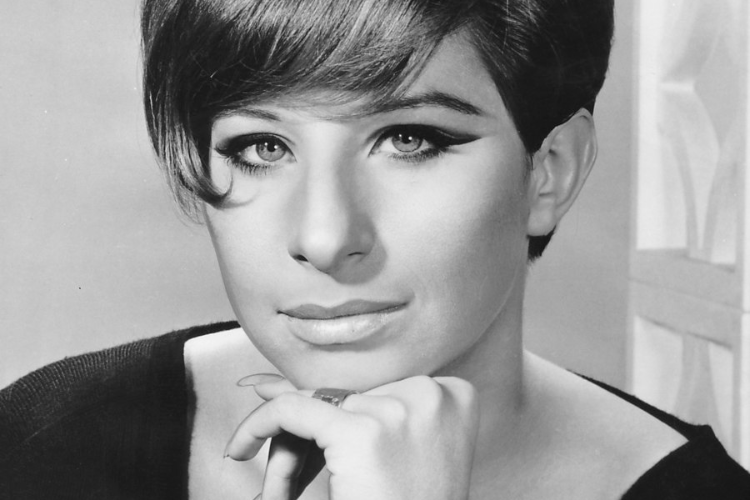

I fell in love with Barbra Streisand. From the moment she appeared on screen, blue eyes flashing, those long nails had me in their grasp. I couldn’t look away.

Here was someone just like me. Odd and unexpected, with skinny legs, but with a presence so electric it reached out and smacked me in the soul. That startling face with its exotic contours, that voice thundering with passion one minute and simmering tenderly the next. The gawky but graceful way she moved, flinging her long arms outward to punctuate a note.

“Funny Girl” was really the story of Barbra Streisand, the ugly duckling from Brooklyn who became “the greatest star.” She didn’t look like anyone else, she didn’t sound like anyone else, but she defied convention and made it work for her.

And that’s what rang true to me. I had frizzy hair, crooked teeth, geeky glasses, and lacked social graces. I didn’t look or think like anyone else, and there were days I felt like a Martian. Here was someone who was also an underdog, but made good on her shortcomings!

I was determined to be just like Barbra. I wandered my high school halls with winged black eyeliner and straightened hair. I made dresses with white collars, cuffs and empire waists, like her outfits in “On A Clear Day You Can See Forever.”

My speech was peppered with Yiddishisms like meshugenah, putz, shlemiel and chutzpah. I took on a Brooklyn accent, and answered the home phone with my best “Hello Gorgeous!”

There was something about Barbra, something I couldn’t quite put my finger on. It was a quality about her, an attitude that resonated deeply within me. Not like she was sending me hidden messages or anything crazy like that.

At the time, I thought it was a great artist’s way of connecting to her audience.

I didn’t realize it, but I had more in common with Barbra Streisand than I could have dreamed. I didn’t know I was actually Jewish.

My parents had emigrated from Poland after World War II, and we were Catholic. I’d even had my First Communion twice—once at our Polski parish, and the second time, with hundreds of other little Polski girls, from a Polski bishop at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens.

One day, when I was about eight years old, my mother and I were on the streetcar. A lady behind us said to her friend, “This girl asked her hairdresser to make her look like Barbra Streisand, so he picked up a hairbrush and broke her nose!” They dissolved into giggles and my mother looked out the window. After we got off the streetcar, she turned to me and said angrily, “That was anti-Semitic!”

I didn’t understand, and asked her what “anti-Semitic” meant. “They don’t like Jews!” my mother exclaimed. I got the feeling she didn’t want to talk about it, so I didn’t ask any more questions.

In LagowskiLand, questions were discouraged. I didn’t dare pry into the lives of my parents. The few times I had, it seemed to upset them. So I left well enough alone. Why would I want to make them unhappy?

The year I turned 13, my father was promoted to a job at the Hamilton Westinghouse plant. A bungalow in the bedroom suburb of Oakville, Ontario, became LagowskiLand. Oakville was famous for being the richest town in Canada, and there were tons of wealthy white people. Our bungalow was in the humble west end, but our neighbors were still pretty WASP.

If I’d felt like a Martian before, now I felt like I had three heads and eight arms. My friends couldn’t help it if they had names like Jones, O’Loughlin, MacKenzie, McGinn, Smith, and so on.

When I was 15, I felt my first real blast of anti-Semitism. At Christmas time, our Polski Catholic friends, the Lewieckis, came over to visit. Mr. Lewiecki sneered, “Barbra Streisand is just like those ugly Jewish girls I went to school with.”

I put Barbra’s Christmas album on the stereo. “Now, if Barbra Streisand could sing a song like that,” he said, pointing to where Barbra was belting out Ave Maria. I looked at Mr. Lewiecki and told him that, in fact, it was Barbra Streisand singing. He turned red and looked at my mother, who retreated into the kitchen.

I got the feeling he had done more than just put down my idol. My mother stayed in the kitchen until it was time to serve dinner, and then could barely look at Mr. Lewiecki.

My mother had sort of a soft spot for Jews. When we were watching “White Christmas,” she’d said, “Isn’t Danny Kaye talented?” I replied that yes, he was. She leaned over and said in a hushed tone, “You know, he’s Jewish.” I didn’t know why she needed to keep her voice down.

I always knew she’d had a rough time during World War II. Neither of my parents had much extended family; my father had a sister in Poland, my mother had distant cousins in France. She had spent the war as a hotel maid in Germany, but didn’t say much about it. My father had been an officer in the Polski cavalry, and spent most of the war in prisoner of war camps.

Any prying I might have done would be met with gloomy silence. They had enough to be heartsick about. My parents survived one war, but another soon brewed between them. Their marriage was troubled, and they fought frequently and loudly. There were bitter accusations about money, which friends were plotting and scheming against them, or just what to have for dinner. LagowskiLand could get hostile.

My mother was anxious and tense, while my father was easygoing and jovial. I loved them both, but was more relaxed with my father. He took me to the library, the skating rink, the park and taught me how to tell time by the sun. My mother taught piano part-time, and instilled a love of music in me, taking me to concerts, the ballet and opera.

Once I left home, there wasn’t much reason for them to stay together. So while it was a shock, it wasn’t a surprise when, one June day in 1990, my father called to tell me that my mother had left him. He sent over an affidavit that detailed why she was leaving him, Item #14 stuck out:

“My husband and I are Polish immigrants, having come to Canada after World War II. I was born in the Jewish faith but converted to Catholicism. My husband has never let me forget that I was originally Jewish and he constantly denigrates me about my origin. As he gets older, he is getting more and more bigoted.”

Wow. Mother thought she was born into the Jewish faith? That she was Jewish? Inconceivable.

Although it was almost midnight, I picked up the phone and called my father. “You know there’s this item #14, where Mother says she was born into the Jewish faith,” I said. “That would mean she’s Jewish.”

“Yes, your mother is Jewish,” said my father.

“What? Mother is Jewish? Why didn’t anyone say anything?” I exclaimed, clutching the phone in a death grip.

“You didn’t ask,” said my father calmly.

I poured out a torrent of questions. What else didn’t I know because I hadn’t asked? Did he realize that if my mother was Jewish, that meant I was Jewish? How could this happen? Why had I been so stupid? Why had I not picked up on the clues?

There was a throbbing in my ears, and my heart was racing. My knees felt weak and I couldn’t stand up. I gripped the side of the desk and got off the chair, making my way to the kitchen. I poured a glass of water and swallowed an Ativan.

Now I understood the tension between my parents. I realized why my mother was so sensitive to comments about Jews. And I realized that I was Jewish. Just like Barbra Streisand.

Initially, both my parents denied I could be Jewish. The two Holy Communions came back to haunt me. I cackled, “No shit. They had to double down because I was really just a little Jew.”

My father shocked me. “You couldn’t be a Jew, they are all money lenders and don’t have real jobs,” he said. “We wanted them to assimilate, but they didn’t want to.” I’d never heard him talk like this before.

But I knew, from all those years of idolizing Barbra, that being Jewish was to be part of a nation of people. I knew about Jewish values—the importance of learning, education, philanthropy, human rights, the founding of Israel.

Barbra had faced oppression in Hollywood, both as a woman and a Jew. Yet she had won every major award in the entertainment world—Oscar, Tony, Grammy, Emmy…. She never compromised her looks, her name or her principles. She wasn’t afraid to question the status quo.

She campaigned for politicians like George McGovern, causes dear to her heart like climate change and women’s rights, and appeared on a TV special marking Israel’s 30th birthday. As Barbra was exchanging pleasantries with Golda Meir, I wondered where else was a woman head of a country? And when Barbra raised her voice to sing Hatikvah, I got goosebumps.

Then there was “Yentl,” my favorite movie, which one critic dismissed as Barbra’s “Jewish valentine to herself.” Here, I learned that it wasn’t always easy for Jewish women. They weren’t allowed to study, or have a voice. But because Yentl wanted more for herself, she found a way. She disguised herself as a boy, Anshel, and became a Torah scholar. And she learned that the questions can be as important as the answers.

And so, finally, did I.

With gentle questions, I finally learned about my mother’s past. She was born Dorota Milstein, and at the outbreak of World War II she had been in the Lwow ghetto. Both her parents, Maurycy and Bronislawa, perished. When she learned the ghetto was to be liquidated in June of 1943, she got false papers identifying herself as a Polski Catholic, Joanna Litniowska. She scraped together enough money to last three weeks, and walked out the ghetto gates, carrying a bouquet of irises. If anyone were to stop her, she would say the flowers were for the commandant, who lived just outside the ghetto walls.

No one stopped her.

Joanna Litniowska made her way to Germany, where she spent the remainder of the war in Berchtesgaden, as a hotel kitchen maid, four kilometers from Hitler’s summer residence. No one suspected she was a Jew.

When I watched “Yentl” after I found out about my mother’s experiences, I burst into tears at the scene “Papa, Can You Hear Me?” Yentl is talking to her late father, asking for his forgiveness, that she is breaking Jewish law by daring to study.

Now the scene was also about my mother, on the lam from the Nazis, asking Maurycy to forgive her for forsaking her Jewishness and taking on a false gentile identity. It was the only way she knew to survive.

In the face of my mother’s courage, and everything I knew about the Holocaust and Judaism, I couldn’t have been prouder to be a Jew. Here, in Canada, I could freely identify as a Jew without fear. Someone asked me if I was going to be as good a Jew as I’d been a Catholic, and I answered, “probably.” But I started attending high holiday services at First Narayever, a traditional egalitarian synagogue. I purchased Yahrzeit plaques for Maurycy and Bronislawa. Maybe I didn’t fast on Yom Kippur or stick to matzah for Passover, but my Jewish consciousness took over. Not just because of Barbra Streisand, or my mother, but for six million reasons.

The more I insisted that I was Jewish, the more distant my father became. He took up with a Polski woman, who was very much into Catholicism and priests. So much so that she’d had an affair with a priest that resulted in a daughter. The woman told everyone that she was a widow. I’m not sure that her daughter even knew the truth.

Yet my father was very much taken with this woman, and I tried to make the relationship work. But she despised me, both because I was a Jew and for the attention my father paid to me. Eventually, she forbade my father to see me, and he didn’t fight back. I didn’t see my father for eight years, and we reconciled only at his deathbed.

In the meantime, Dorota/Joanna, as I came to think of her, was able to talk a little about her parents. They were assimilated Jews, and Maurycy was the oldest of 11 children. His father had died young of a heart attack, leaving his widow with a sizeable brood to care for. Maurycy was a teacher who had started a trade school for Jewish boys. Bronislawa was a devoted wife and mother, with a large extended family who were very close. She was famous for her shapely legs, a way with needle and thread and fashionable wardrobe.

Eventually, Dorota/Joanna, not only accepted the fact that I embraced my Judaism, but came to respect it. And sometimes when we went out, and a dark-haired waitress or shopgirl would serve us, my mother would ask, “Do you think she’s one of us?” Her Jewdar went into overtime!

I asked her, “What did you think when I was worshipping Barbra Streisand? Why didn’t you say anything?” And she replied, “I thought you had figured it out.”

No, I hadn’t. And I still haven’t figured out what it really means to be Jewish. But thanks to Barbra, I’ll keep asking the questions.

Krystyna Lagowski is a Toronto-based freelance writer specializing in automotive, and is the author of drivelikeagirl.ca. Her obsessions include Barbra Streisand, Burmese cats, old Eastern European cars, genealogy, and Judaism.