A Woman’s View of Circumcision

Circumcision isn’t my thing. I mean, literally. As a woman, I lack the proper anatomy parts to be able to experience this particular rite of passage on my own body. Although circumcision is necessarily outside my physical being, as a member of the tribe, I am meant to consider ritual circumcision — the “bris” or brit milah — a spiritually significant component of my Jewish identity (though precisely whose departed foreskin is meant to provide me with my Jewishness is not entirely clear). So the recent brouhaha over a proposed circumcision ban in San Francisco raised a lot of powerful issues for me, highlighting my ongoing internal battle of allegiances between feminism and Judaism.

My feminist self has always felt awkward about circumcision. So much of our liturgy refers to the centrality of the bris — literally “the Covenant” — like the Grace After Meals, in which we thank God for “the Covenant that you engraved in our flesh.” When I read this, and chant it aloud, I shudder with the ongoing reminder about how excluded I am as a woman. This prayer assumes that only men are reciting it, that “our” flesh is the community of men who are the primary owners and recipients of the heritage. Years ago I read a commentary on this passage suggesting that women become part of this collective entity when we are married, experiencing bris vicariously through our husbands. This just adds insult to injury. I am not only ignored, but also rendered invisible, reminded that the correct state of my being is hidden behind a man. Judith Plaskow describes this in Standing Again at Sinai: “When God enters into a covenant with Abraham and says to him, ‘This is my covenant which you shall keep, between me and you and your descendants after you: Every male among you shall be circumcised’ (Gen. 17:10), women can hear this only as establishing our marginality.”

Bris has a way of erasing the lives of women from the moment we are born. The bris ceremony becomes a major celebration of a boy’s birth, leaving the arrival of a girl ritualistically unnoticed, except in certain Sephardic communities, where there is a centuries-old tradition of honoring the birth of a Jewish daughter. The past generation or two of women have sought to fill in that void, but it’s still an uphill battle. Some expectant grandparents, for example, still wait to make appropriate travel plans based on gender — for a boy, of course they will attend the bris, but for “just” a girl they might not rush to make the trip. In an adult course on the Jewish lifecycle I once taught, I had to use a curriculum with the following chapter titles: “Bris, Bar/ Bat mitzvah, Wedding, Death.” The educators seemed to lack any awareness that there’s more to a birth than the bris. This classic vision of the Jewish lifecycle, emphasizing the bris as the quintessential moment of birth, practically ignores the existence of girl babies and the experiences of women. This dismisses the entire experience of childbirth, as if to say we’re not really celebrating new life — we’re celebrating a new set of male genitals for the Chosen People. Howard Eilberg-Schwartz has written that “Since circumcision binds men between and across generations, it also establishes an opposition between men and women”

My Judaism makes other points. My objections as a thinking woman notwithstanding, there have been moments in my life when I have pushed aside my feminist consciousness and taken a more passive approach towards accepting Jewish tradition. When my son was born, I found myself having nagging thoughts that I ultimately put away in a drawer in my mind, the most recurrent among them: “We’re doing what to his body?!” This thought was indirectly validated at the bris by my mother, who made sure that I followed her family’s tradition of not allowing the mother anywhere near the baby during the ritual. She kept pushing me to the back of the hall, and even wanted me to be in a separate room. She couldn’t exactly say to me, “Generations of mothers have been horrified by this custom,” but that secret knowledge was there.

Of course we did the bris anyway. Not doing it was not an option. If 3,000 years’ worth of Jews were doing this, I felt too small to pass on it. I still do. It was that voice in my head saying, This is really important. I am a Jew. My grandfathers did this, as did their grandfathers. Jews risked their lives in the Holocaust and in the Inquisition and under Hellenism to make sure that they could do this, and who am I to kvetch about it? The grandiosity of “entering the Covenant” felt too huge for me to question for my son. A little blood in exchange for an eternity of belonging and identity? Not such a bad deal.

It is hard to articulate a rational explanation for this practice of making our babies bleed, beyond “That’s what we’ve always done,” and I know how weak an argument that is. Even Harry Brod, noted professor and scholar of masculinities, in an article entitled, “Circumcision and the Erection of Patriarchy,” wrote: “For many Jews, the circumcised penis is the defining mark of being a Jew…. [T]he idea that circumcision confers Jewish identity has a deep and powerful hold on many Jews, even those not otherwise particularly observant.” Even opponents of patriarchy are reluctant to oppose a tradition that seems so essential.

Still, the recent events surrounding the circumcision ban proposed in San Francisco took me back 16 years to those moments of doubt. Some of the opponents’ points resonate with me, such as those of “Mothers against Circumcision,” who claim that that one out of every 500 circumcisions goes wrong, that the foreskin is essential for sexual fulfillment, and — mostly — that it’s immoral to alter your child’s anatomy permanently for no particularly good reason especially when the child cannot voice an opinion. On a website called “Beyond the Bris,” 21-year old Shea Levy wrote a blog post, “To the Mohel who cut me:” “Almost every single day, for as long as I can remember, I have at one point or another felt discomfort in the tip of my penis…. The permanently uncovered portions of my glans are calloused.… The area underneath the folded shaft skin that remains regularly collects dust, lint, and other foreign particles… I am not capable of the same level and variety of physical pleasure that would have been available to me had I been left intact…. Sexual activity causes more friction than it should.”

But I’ve asked some circumcised men how they feel about this essay, and many disagree. “Dust, lint and other foreign particles?” one man replied. “Seriously?” Indeed, a survey of some of the research indicates that infant circumcision gives 100% protection against cancer of the penis, prevents a common inflammation of the glans called balanitis, makes urinary tract infections 10 times less likely in babies, reduces the incidence of cervical cancer by 20% in sexual partners and makes men eight times less likely to contract the HIV virus.

While these points are being argued across the blogosphere, the proposed San Francisco measure, with a $1,000 fine and one-year prison term for the performance of circumcisions on males under 18, seems extreme. Worse, the language of violence and hatred among its staunchest proponents are more troubling than the debate over infections or sexual pleasure. Some of the language surrounding the ban smacks of anti-Semitism. In particular, the comic book Foreskin Man, with its “Monster Mohel” character, has some profoundly disturbing echoes of the Elders of Zion. It was created by Matthew Hess, president of the MGM Bill organization that proposed the ballot measure. (MGM stands for “male genital mutilation.”) The comic book stars a blond, Aryan-looking caped superhero whose mission is to save baby boys from the sharp knife of the gnarled, beadyeyed, hook-nosed, grimy-looking, black-clad mohel. I agree with the Anti-Defamation League statement that the comic book has “identifiably Orthodox Jewish characters as evil villains, [who are] disrespectful and deeply offensive… This is an advocacy campaign taken to a new low. No matter what one’s personal opinions of male circumcision, it is irresponsible to use stereotypical caricatures of religious Jews to promote the anticircumcision agenda.”

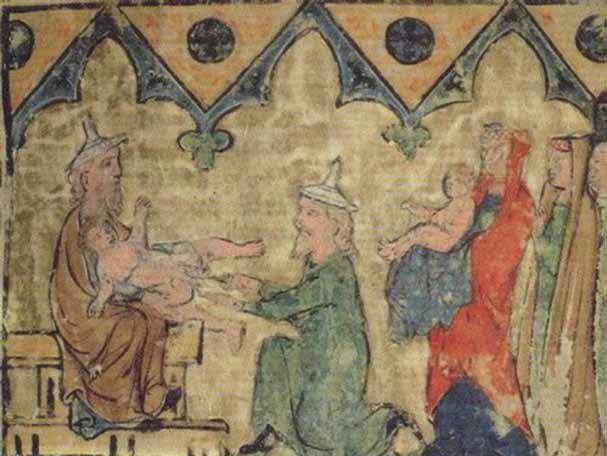

It is easy to see this proposed bris ban in light of the narrative of Jewish oppression. As the Jerusalem Post noted in an editorial, “Opposition to brit mila dates back to ancient times. The Romans were particularly hostile to the practice before and after the destruction of the Second Temple. It was seen by the pagan Romans as an attack on the Hellenistic adoration of nature, considered perfect and a reflection of the will of the gods.” As much as it’s hard to explain why bris is so important for Jews, it’s even harder to explain why the practice brings out such hatred among its opponents. It is irrational anti-Semitism rearing its ugly head in the strangest of places — surrounding the genitals of Jewish men.

The politics of such rituals? Really, all this excitement about the phallus. How Freudian, I suppose. Still, in attempting to avoid the obvious — that this is just another story about men and their masculinity, because hasn’t every culture in the history of humanity had this obsession in one form or another? — I wanted to first try and understand why this is so important to Jews. If God wanted us to have a sign of the covenant, He could have asked for something more benign — a gold necklace, a red dot on the forehead, or perhaps dyeing our hair green over the ears. Even a small tattoo seems better than this (though ironically, tattooing is against the Torah but somehow this isn’t, which is hard to fathom). Although, to be fair, I think about the Maoris with their facial tattoos and some African tribes with piercings and neck-chokers, and suddenly circumcision doesn’t seem so bad. But these thoughts do remind me that the entire practice is primal, a marking on the skin in the most intimate of places to identify allegiance.

In order to gain some insights into the meaning of this ritual for practicing Jews, I did what any self-respecting researcher in the year 2011 would do: I went to crowdsourcing. I asked my Facebook friends and listserv groups how they understand bris. One friend cited Genesis, saying that circumcision is meant to ensure that all progeny emerging from this organ be part of the covenant. This blunt statement exacerbates all my feelings of exclusion — especially considering women’s roles in producing these progeny. In the days of Abraham, added another friend, men made pacts by holding one another’s crotch — like swearing on one’s descendants. Seen this way, the penis is just a very significant part of how men communicate important ideas, apparently.

Among the other responses I received:

• “We are asserting our identification with G-d and our commitment to use our entire bodies for great purposes.” That’s beautiful, but I could have made a mark on my elbow or ear for the same effect. In fact, one might argue that marking a body part that is not often seen in public (urinals and locker rooms notwithstanding) is not the best way to send a strong message of identification.

• Maimonides wrote that circumcision is about “the wish to bring about a decrease in sexual intercourse and a weakening of the organ in question, so that this activity be diminished and the organ be in as quiet a state as possible.”

• “It is a foundation of Judaism that we are to control our animal desires and direct them into spiritual pursuits. Nowhere does a person have more potential for expressing ‘barbaric’ behavior than in the sex drive.” Another friend quoted a related passage from the Sefer Ha-hinuch: “To remind him that just as he perfects his body, so to must he perfect his soul through his actions.”

Athena Gorospe, in Narrative and Identity, expounds on this idea around the biblical concept of “circumcision of the heart” (Deut 10:16). “A circumcised heart is associated with the ‘loosening of the neck’…to remove the ‘hardness’ that keeps a person’s emotions, desires, mind, and will from fully surrendering to Yahweh. It is to make the heart ‘the organ of commitment’ more sensitive and responsive to God….Physically, to circumcise is…. to uncover the sheath and expose the organ so that it becomes more sensitive and responsive to touch… to remove anything that hinders the person from being sensitive and responsive to the divine will.” Although the reminder that we all need to be working on self-improvement and developing compassion and sensitivity towards the other is one of the Jewish world views that I most love and connect to, ideas that the male body needs to be curtailed and even “perfected,” that sex is by nature barbaric, and that all our desires need to be restrained, raise some difficult theological and moral questions. And, ironically, it confirms the assertion by proponents of the ban that this procedure is bad for men’s sex lives.

Opponents of circumcision put forth some flimsier ideas. Graphic artist Hess, who wrote the San Francisco ballot language, called it a “double standard,” that cutting the genitals of girls is illegal but cutting the foreskin off boys is acceptable. I find this argument to be an affront to women who have endured female genital mutilation. As Ayaan Hirsi Ali so painfully recalls in her book Infidel, female genital mutilation removes sexual satisfaction, routinely causes some extreme, life-threatening health problems, and severely oppresses women by attempting to make them docile, subservient and asexual. Male circumcision does none of those things, and for the most part has little impact, if any, on a man’s life. Even blogger Shea Levy’s suffering cannot even begin to compare to Hirsi Ali’s. Indeed, feminists have a huge issue with calling female genital cutting “female circumcision,” because it suggests that it’s as painless, normal, and beneficial, as male circumcision, which it is not.

Proponents of the San Francisco ban argue that parents should not be allowed to force a decision on a young male child. One can sympathize with this idea in principle, but parents make many other seemingly odd decisions about a child’s body without first getting consent — including vaccinations, ear-piercing, and even leashes and restraining straps. While I believe that we need to give our children as much freedom as possible, this is not an absolute practice and needs to be weighed against other factors. Indeed, male circumcision done later in life, whether for health or religious reasons, is much more painful than having the procedure as a baby.

But there seems to be more than logic behind the efforts at banning circumcision of baby boys. Jena Troutman, the Santa Monica woman who submitted a similar proposal for her city but then withdrew it, stated this entire position with some strange ideas and overt hostility. She reportedly told Fox News, “I don’t have the time or the energy to argue with everybody, but you shouldn’t go around cutting up your little babies. Why don’t people [expletive] get that? For me, this was never about religion. It was about protecting babies from their parents not knowing that circumcision was started in America to end masturbation.” Huh? This diatribe alone makes me want to join the other side.

Meanwhile, supporters of circumcision, which include a mixed group of Jews and Muslims, successfully petitioned the San Francisco court, which ruled in July that the measure violates freedom of religion, although this ruling will most likely be appealed.

While I continue to be troubled by new and creative manifestations of anti-Semitism, the truth is, I’m still not really sure how I feel about the bris. This entire series of events mostly makes me wonder about the centrality of masculinity in our cultures — Jewish and Western. It feels like this entire story is a kind of male turf war, a battle over whose penis is superior. It’s as if the uncircumcised penis is as much of a threat to Jewish identity as the circumcised penis is to Gentiles. It reminds me of an incident recently recounted to me which occurred in Canada a few decades ago, when a European-born non-Jewish man discovered that he had inadvertently given permission for his newborn son to be circumcised by doctors in the hospital. He burst into the ward threatening to kill the medical staff, screaming hysterically, “You made my son a Jew!”

Howard Eilberg-Schwartz wrote in 1995 that “[I]t is time to find a different symbol of a boy’s entrance into the community. Instead of cutting our sons, we might celebrate their masculinity. A more appropriate symbol would be a nurturing act, one that would affirm a boy’s relationship to a loving father, both his own and that of his God. We might, for example, feed our sons, since a meal is also a traditional symbol of covenant….Feeding our sons, rather than wounding them, would be a symbol of our nurturing relationship to them.”

Circumcision is in many ways about men defining their own Jewishness. There is also an anti-Semitic backlash, profound hatred for that Jewish male assertion of masculinity. Symbolically, the penis is ultimately about male power, and the fight over the circumcision ban is just another manifestation of that male struggle.

As much as we should defend the rights of the Jewish people to maintain an ancient culture, we should also defend the rights of Jews to form alternative rituals, especially ones that reflect the compassion and inclusivity that should be at the heart of Jewish life. And as an added “bonus,” a non-phallic ritual for bringing our children into the Jewish Covenant would welcome both boys and girls as equal members of the Jewish people, from the moment they are born.

Elana Maryles Sztokman is the author of the forthcoming The Men’s Section: Orthodox Jewish Men in an Egalitarian World, to be released in November by the Hadassah Brandeis Institute, and is a contributing writer at The Forward Sisterhood blog.

A Vindication of the Rites of Penises?

Lilith editors discussed circumcision recently in a podcast with editors at the Forward newspaper. A few highlights:

Susan Weidman Schneider: There has been so much uneasiness about male circumcision, even among Jews who end up circumcising their baby boys. On the one hand, it’s an important part of the tradition and also part of what ultimately, they feel, is going to make that child look like his father. We’re attached to it. But on the other hand, we’re repelled, frightened and alarmed, and probably have been since time immemorial.

Susan Schnur: I did my doctoral dissertation on college hazing, which was about men’s initiation rites. This is an initiation of boys into the fraternity of Judaism. Initiation rites are always embodied, there’s always an ordeal, and there’s often scarification. Circumcision is a mutilation; that’s part of its power. If you were a Christian looking at the centrality for Jews of this rite, you’d register the stunning atavism — that’s why it’s so potent. As for females, we were invisible. We know this because circumcision is an entry into a fraternity that we never have to get. Women “tend and befriend,” as the anthropologists say. We don’t have to know that we’ve entered the club of men and that we won’t be kicked out. That’s what these rituals are about, a very primitive, very absolute entry into a world. In terms of people’s ambivalence, the atavism here speaks to something beyond mores and socialization, so it’s seductive. It’s frightening to keep it, and it’s frightening to give it up.

Listen to full podcast.