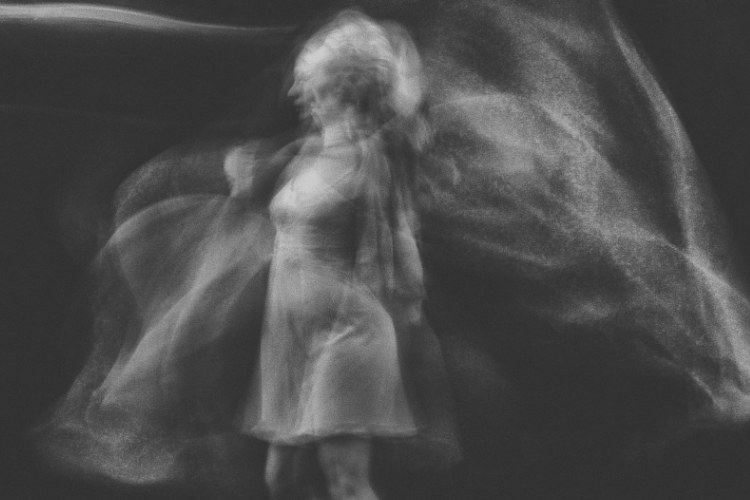

Becoming The Dybbuk

Once upon a time a woman named Leah was allowed to be in a story because she was getting married. Her father picked her a rich husband. Then her dead boyfriend possessed her, because if a woman’s gonna take up space in a story she must not be a woman. Then they learned that Leah had been promised to her dead boyfriend before she was born. She screamed why don’t I have any agency, but no one could hear her. So, they did an exorcism and got her unpossessed. Then she killed herself to be with her dead boyfriend or maybe she just wanted to be left alone.

In 2020, Theatre J invited me to participate in their Yiddish Theatre Project, which commissions playwrights to contemporize Yiddish plays and stories. I was intrigued. My relationship to Judaism was evolving. My play WE ALL FALL DOWN, about a family of cultural Jews attempting their first Passover Seder, was a hit at the Huntington Theatre in Boston. It seemed I touched a cultural nerve by writing about feeling not Jewish enough. Turns out a lot of people have that feeling about their own culture or religion.

Growing up in a non-religious family in Westchester, NY, I felt like Judaism belonged to the girls who wore chai necklaces and talked about youth group. Judaism belonged to the boys who went to Israel and came back keeping kosher. Judaism belonged to my cousins who could read the Four Questions in Hebrew. My name, Lila, which means night in Hebrew, was the only Hebrew word I knew in the Seder. Did I belong to Judaism? Did it belong to me? When I was a teenager, I learned that Lila means play in Sanskrit. That fit me more. Theater was my life, my passion, my sanctuary. Judaism was a thousand bat mitzvahs in a ruffled purple dress where I didn’t know the words.

As a young adult, that alienation continues. In New York, rushing down 7th Ave to get to rehearsal in a long skirt and my curly hair is in a kerchief. I’m eating a bagel. The guys at the Chabad truck yell “Are you Jewish?”

I shook my head and kept walking. I moved to San Diego for grad school, attend a happy hour on Rosh Hashanah. I bring apples and honey. Someone asks me, “what’s that for?” Could they really be asking me? There had to be someone who was actually Jewish to answer. But there wasn’t. So, haltingly, I answer.

Fast forward, I’m a parent now living in Somerville, outside of Boston. After a long search, my husband and I find a temple where I feel comfortable. We join TBZ in Brookline, led by two kick-ass lady Rabbis with a focus on social justice. I can sign onto that. And I do want my daughter to have the belonging I didn’t. It’s a great community. I start to let down my guard and relax a little into Judaism. I also come out as bisexual. I’ve always been quietly bi and quietly Jewish and the volume comes up on both at the same time.

So then, I get this commission from Theatre J in 2020 and Covid starts. After I figure out running a preschool in my living room, I start to research Yiddish plays and stories to adapt. I’m grateful for work I must do as a modern plague spreads and uncertainty prevails. How hard could it be to pick a play or a story? My plays shine light on the stories we don’t tell about women. I center the heroines we don’t usually meet. I read and I read and I realize I have a problem. There are very few women in Yiddish plays and stories and even fewer of them speak. The women I found were:

A mother with rain on her face

A paralyzed Princess

A childless Queen

A fickle Wife

Countless unmarried daughters

A silly servant girl

Not only do they not pass the Bechdel Test, these women don’t even talk! Oy. They were all so victim-y, so disempowered. I started to resist the assignment. My friend who runs Theatre J recommends I look at The Dybbuk. There’s a woman at the center he says. I read it. There is a woman at the center, but it’s largely because she’s possessed by a dead man. I wrestled with it. I was intrigued by the haunting aspect of it. The Dybbuk’s other title is Between Two Worlds and I was drawn to that. I struggled with the fact that it’s touted as this great love story that transcends death and I experienced it as a powerless woman being forced to marry and then getting possessed and then killing herself. If this is a story that centers a woman, maybe I was better off with the mother with rain on her face. But something in me gravitated towards The Dybbuk.

I wanted to fill my head with women’s voices before I started writing, so I interviewed 24 Jewish women of varying backgrounds. I asked them about Dybbuks, Jewish Weddings, and Gender/Sexuality in Judaism. I interviewed women who were Rabbis, Cantors, Scholars, Theatre Artists, and women who grew up speaking Yiddish. And something magical happened during these interviews. I felt something unexpected – deep connection. Turns out I was one of these Jewish women. I had been so busy feeling excluded that I hadn’t realized that I belonged.

My first draft arrived in bursts. My Dybbuk is a queer love story between Leah and her best friend. Her friend is mentioned briefly in the original and I burst her out of the subtext. As I wrote, I found parts of me that had been hiding. I created a queer retelling of this old Yiddish story and a queer Jewish me came into focus. My writing helped me feel more comfortable in worlds where I’d always felt like an outsider. My sexuality and my spirituality were connected. I could bring the women from this story out of the shadows. And bring myself too.

In the original story, Leah’s dead boyfriend is a Dybbuk and comes back and haunts her by possessing her. He takes over her body and takes over her voice and suddenly she is the center of the story. This infuriated me. What’s wrong with her actual voice? So, I wrote this monologue.

LEAH’S MOTHER:

I remember in Hebrew School

They’d say

It’s your duty to remember

It’s your duty to our stories

It’s your duty not to fuck this up.

And I remember thinking

but that’s not me

I’m not in that story. Or that one.

I wasn’t brave enough to say it

But I was brave enough to think it.

During my Bat Mitzvah I stood on the bima

and I thought

I know I’m supposed to believe this but I don’t

Because I don’t see myself in it.

This is someone else’s story and I’m supposed to pretend it’s mine.

I wasn’t brave enough to say it

But I was brave enough to think it.

When my daughter was born

My husband wanted to give her a Hebrew Name

And I thought why?

Hebrew is a language for men.

Everything about it.

How it it’s written, why it’s written, who it’s for

It might as well have testicles.

Why would we give a name written in testicles to my daughter?

I wasn’t brave enough to say anything

So, my daughter’s Hebrew name is Leah which means delicate or weary

I wanted to give her a strong name

a name that meant something like BULL or POWER SAW or FUCK YOU

But there are no girls names in Hebrew like that.

So we went with Leah.

Delicate or weary.

The two choices we have.

Or maybe it’s three.

Delicate or Weary or Dead.

I wish I could go back to Hebrew School.

I’d interrupt my class and I’d say

“For the purposes of Judaism, consider me a man.”

Because I want to be in the stories

Because I want to read and argue

Because I want a name that’s strong.

Something healed in me when I wrote that monologue. I can question – it’s very Jewish of me to do so. I can belong to this tradition that sometimes infuriates me. It’s like any other family member. I can let go of feeling excluded.

I thought I had to get as small as the women in these stories to represent them, but instead I find myself a gladiator crushing walls to make space for them to breathe.

I am so proud of this play. It was workshopped at the Kennedy Center and had a public reading at Theatre J. I can’t wait for it to be produced. It is becoming more and more itself. It makes an old story new.

My Dybbuk is a romance between two women. My Dybbuk is funny and heartfelt and queer and feminist.

My Dybbuk is me.