9 to 5: Feminism and the Labor Movement

Ellen Cassedy, author of Working 9 to 5: A Women’s Movement, A Labor Union, and the Iconic Movie, grew up hearing her Lithuanian-born grandfather’s stories. Some centered on socialism but he also spoke about seeing Rose Schneiderman of the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) rail against the exploitation of female garment workers and describe the urgency of the workers’ campaigns for decent wages and improved working conditions. Cassedy found these stories thrilling and when it was time for her to write her college thesis, she researched WTUL history. Inspiration followed–and simmered–until, as a newly-minted university graduate, she took a job as an office worker at Harvard. It was 1971 and alongside her friend Karen Nussbaum, another Harvard secretary, the pair began talking about being on the receiving end of low pay and disrespect from their condescending male bosses.

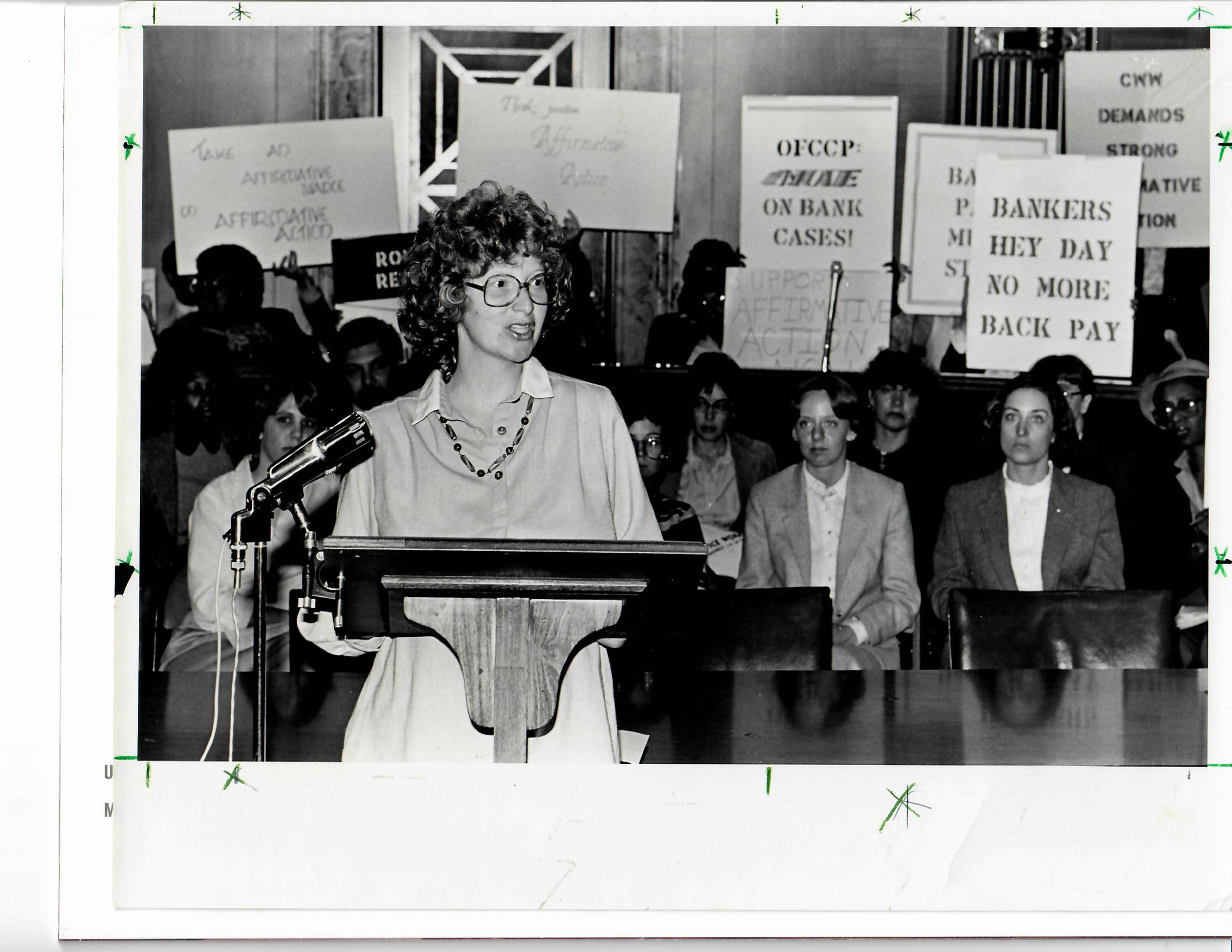

Outreach to other Boston-based office workers followed and in short order, a group of 10 disgruntled female typists and clerks created what became 9 to 5.

With the organization celebrating its 50th year, Cassedy’s Working 9 to 5 is both a celebration of the tenacity of this small group and a critical assessment of its successes and failures, all set within the context of the broader US labor movement. Cassedy spoke to Eleanor J. Bader in early February.

Eleanor J. Bader: Did the initial founders of 9 to 5 have roots in the labor movement?

Like me, Karen Nussbaum came from a liberal Jewish family that supported unions. Janet Selcer’s parents were union members, too. Her mom was a union teacher and her dad was a musician and member of the orchestra union. Not all of the early members shared this history but, as I write in the book, they were sick of the stereotypes that painted secretaries as decorative objects, officious gatekeepers, or airheaded bimbos. They were also sick of being treated as if they were invisible, as if their work did not matter. They knew what they did was essential to the company’s functioning and wanted this to be recognized.

EJB: You write that you are naturally shy and are not a natural organizer. How did you find your voice so that you could play a leadership role in 9 to 5?

EC: Heather Booth, an organizer who had worked with Saul Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation in Chicago, co-founded the Midwest Academy in 1973. Part of its mission was to train women to become organizers, something that Alinsky’s IAF did not prioritize. Feminism was a huge part of the coursework the Academy offered.

Shortly after the Academy started, I was sent by 9 to 5 to attend its first weeks-long class in community organizing. I was part of a cohort of 18 women that included several leaders of NOW. Heather focused on making sure that women–the backbone of most organizations–got the credit they deserved. Together we learned to demand things we could actually win. The Academy called it a ‘win-some-reforms-right-now’ approach. We also learned the necessity of making organizing fun.

Although I’d always been a good student, I gave myself low marks at the Academy. I felt I was terrible at all of it and had to give myself a lot of pep talks. But I also realized that movements need all kinds of people, including those of us who are shy. This self-awareness helped me support less aggressive members who were more comfortable staffing a table or conducting a survey than they were out on the picket line.

EJB: Was 9 to 5 explicitly feminist when it began?

EC: We discovered pretty quickly that using the word ‘feminist’ was not going to help us organize since many secretaries told us, explicitly, that they did not identify as feminists or ‘women’s libbers.’ At the same time, the ideas of feminism–being treated respectfully, being paid the same wages as men doing comparable work, and not being forced to do personal errands for the boss, had seeped into their consciousness. They wanted equity. They wanted fairness. They wanted respect. That was what we were organizing to win.

EJB: Did 9 to 5 receive support from groups like NOW or the Women’s Action Alliance in the 1970s or 80s?

EC: Not that I recall. We felt somewhat different from these organizations. We stressed that we wanted to make life in the typing pool better and, while we welcomed women who wanted to climb the corporate ladder, we were also interested in helping workers who did not want to do this. We worked hard not to get out ahead of what workers themselves wanted. We created measurable goals to demonstrate that when women got together, we could win. We made sure that our organizing was not too solemn. We used the phrase Roses and Raises–an echo of the early 20th century garment workers’ slogan Bread and Roses. For me, it was particularly powerful to know that I was part of a historic chain of women labor organizers. I wanted to touch history, even as I recognized that we needed to chart our own path as activists.

EJB: What do you consider 9 to 5’s greatest achievements?

EC: We did so much! We took on some of the most powerful businesses in the country: insurance companies, banks, colleges and universities, and more. We helped make sexual harassment illegal and even though it is still rampant, we made some inroads in stopping and punishing it. We emphasized that sexual harassment on the job is bound up with women’s power at work. Furthermore, the practice of separating Help Wanted ads into male and female jobs has been discontinued, pregnancy discrimination is now illegal, and the wage gap has narrowed. These are all things I’m proud of.

Another thing I’m proud of is that we succeeded in creating a multiracial organization. Although the initial group that founded 9 to 5 was diverse in terms of class backgrounds, all of us were white. We knew that we had to move past Boston’s mostly-white office workforce if we wanted to create a multiracial membership and leadership team. We expanded our organization to Atlanta, Baltimore, and Cleveland and succeeded in our goal.

EJB: Are you optimistic about the future of labor organizing?

EC: I know that it can be harder to be a worker today than it was 50 years ago. Too many jobs are still dead ends and the gig economy has forced some people to work two or three jobs to make ends meet. Too many people still lack paid vacation and sick time and the relentless pace of work at companies like Amazon shows us that there is plenty left to do.

The good news is the current wave of organizing among tech workers, restaurant workers, graduate students, Congressional aides, fast food and warehouse workers. A recent survey found that 71 percent of Americans support unions; that’s the highest it has been since 1965, so I have high hopes.

But I am also realistic and know that it won’t be easy. The union-busting industry that developed in the 1980s is strong and employers like Starbucks and Amazon continue to act as if they don’t have to negotiate with unions. Still, if 9 to 5 taught me anything, it’s that collective action can lead to change and win impressive victories.