Novelist Fran Hawthorne on Secrets and Lies

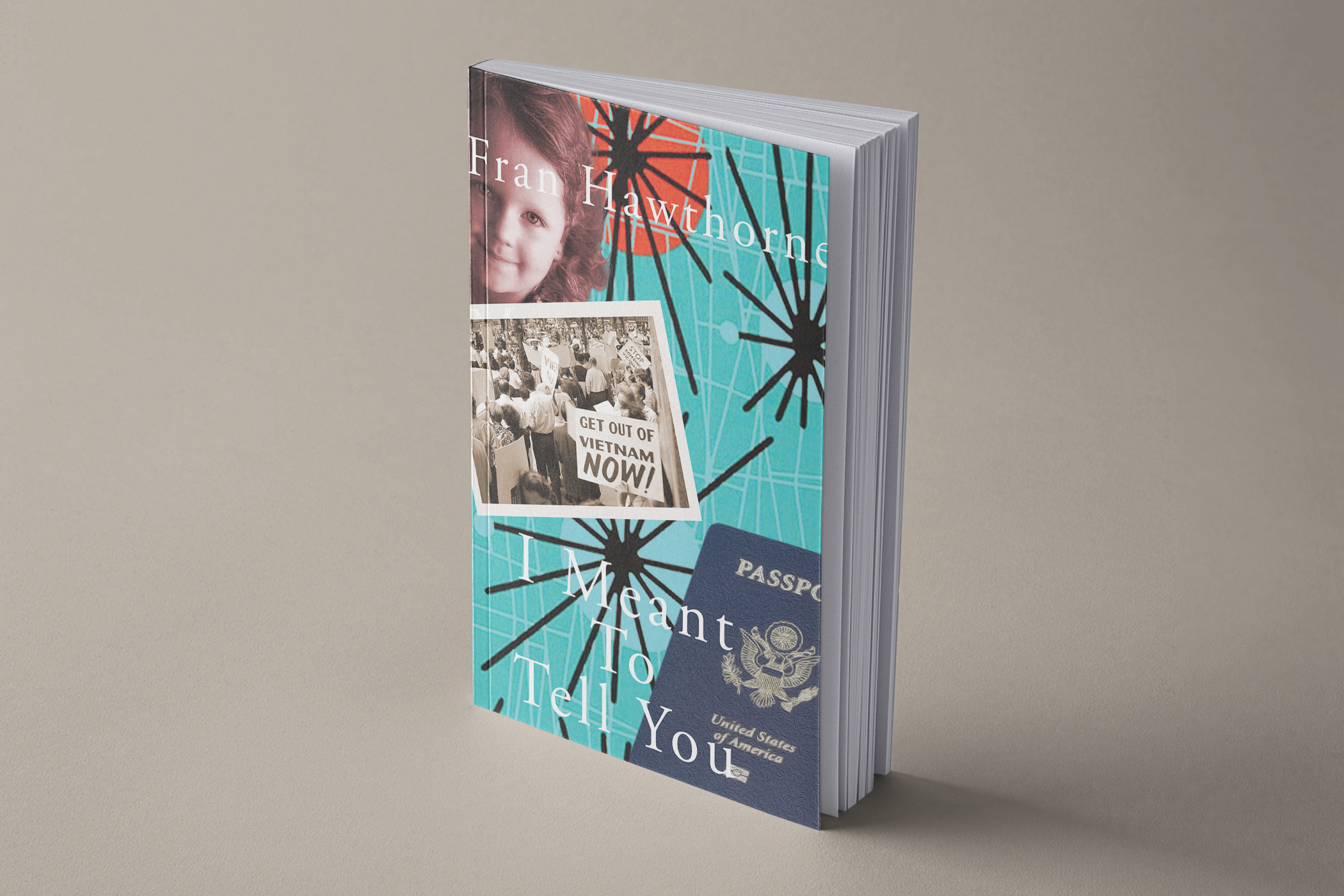

In Fran Hawthorne’s latest novel, I Meant to Tell You (Stephen F. Austin State University Press, $22), the titular secret is a big one–an arrest for felony kidnapping that one member of a couple, Miranda, fails to tell the other–her fiancé Russ–about. But it’s not the only omission, betrayal, or falsehood. Hawthorne talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the power of secrets, both long kept and finally exposed.

LILITH: Is Miranda’s failure to tell her fiancé about something she’s done in the past a betrayal? Are there other characters who have been betrayed?

FRAN: That’s a good question. I think Miranda’s behavior straddles a hazy line. She has certainly kept an important piece of her past a secret from her fiancé, Russ, which is a form of dishonesty. It’s more serious than what we call a “white lie.” She has betrayed the expectation of basic honesty that should be part of a marriage. Yet, I hesitate to label it a betrayal, because I think “betrayal” usually implies a foreknowledge that the person who’s betrayed could be harmed. In Miranda’s eyes, the secret she’s hiding shouldn’t affect Russ’s career (although she doesn’t probe very hard to find out if that assumption is correct). She’s protecting herself, but she’s not trying to hurt Russ.

Of all the book’s many other secrets, they range from outright betrayals of promises, to secrets of self-protection, to secrets that are intended to protect someone else, and even unintentional secrets. As one character explains, “It just happened … I never made a conscious plan about if or when I’d tell you; I only coped moment by moment.” The “right” moment to tell that secret never seemed to arrive.

LILITH: Let’s talk about mothers and daughters—is Judith justified in what she’s not told Miranda? How does her ultimate revelation impact her daughter? Does it change their relationship changed for the better?

FRAN: As the author, I made the decision that Judith wouldn’t tell Miranda her important secret, based on a gut feeling about what most people might do in her shoes to avoid dealing with a sensitive situation. Yet I don’t think her lack of honesty is justified. Essentially, I think Judith concocted an exaggerated fear of the impact of the truth. In fact, Miranda is so shaken up by her mother’s dishonesty, that she runs away without knowing where to go. Does the revelation make their relationship better or worse? I’d love to know what readers think!

LILITH: How about what Ronit has with her daughter; are her actions justified?

FRAN: Ronit’s husband, Tim, has become so abusive that Ronit clearly must get herself and her young daughter, Tali, away from him. Still, does she need to take such a drastic step — to secretly and illegally whisk Tali nearly six thousand miles to Tel Aviv? The repercussions for Ronit and Tali turn out to be so awful that the answer to your question might seem to be: No, her actions aren’t justified.

But back in early 1996, when this part of the novel takes place, there was a lot less public knowledge about domestic violence than exists today. It wouldn’t occur to either Ronit or Miranda to seek out local women’s shelters or abuse counseling in … the Yellow Pages? (Popular Internet search engines didn’t yet exist.) The only shelter that Ronit can think of is with her family in Israel. Nor do the two women realize that they’re breaking the law by taking Tali. As a mother, I totally understand the instinct, though I don’t think I would have had the foolhardy courage to carry it out.

LILITH: You’ve set some key scenes of the story in the 1960’s; what aspects of that period made you want to write about it? Are there parallels between the activism of the 1960’s and the present or if not, how have things changed?

FRAN: Do we have a responsibility to use the lives we’re given, to try to leave the world a little better than we found it? That’s always been a guiding philosophy for me, and I knew that I wanted to make it a sub-theme of this book. The 1960’s – that wild, unique era of antiwar protests, civil rights marches, and counterculture rebellion—was a perfect setting for illustrating that theme.

However, I didn’t want to place the novel wholly in the 1960’s, because that milieu was too dramatic; it might overwhelm my characters and plot. Instead, I would use it as a point of comparison.

Throughout her life, Miranda has looked up to her parents and grandfather as role models for their history of social activism. Her grandfather was a union organizer, and her parents were leaders of the protests against the Vietnam War in the 1960’s. Living in the early 2000’s, Miranda constantly belittles her own career choices, frustrated that there aren’t any great causes that would enable her to carry on the family tradition. A rally she attends, protesting the looming war in Iraq, is paltry compared with her parents’ antiwar demonstrations battling club-wielding police in Chicago and New York. In her job, she feels as if all she does is gather tiny specks of data for a tiny section of a report on drug prices.

Miranda has a point. Many historians have noted that today’s mass movements seem to lack the passion of their forerunners. According to one popular theory, the fault lies with social media: Because it’s too easy to organize and spread the word, participants aren’t as committed as they were 50 or 60 years ago. It would be nice to think that there’s also less injustice to protest these days, but I’m with Miranda on that issue. If you care enough, you’ll find a way to do some good in the world.