A Poet Goes Toe-to-Toe with Death, Sex, Judaism and Family

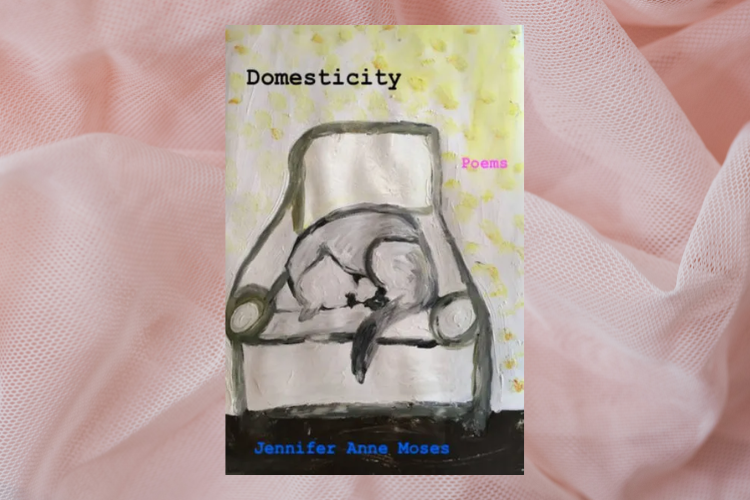

In Domesticity (Blue Jade Press, $15.00) her first collection of poetry, Jennifer Anne Moses goes toe-to-toe with death, aging, nature, sex, abuse, Judaism, and the complicated thing we call family. In a conversation with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough, she discusses these themes and shares her belief that poetry is a way to express our yearning to be in relationship with the Divine.

YZM: You’ve written in several other genres, but this is your first collection of poetry; what does that feel like? What does poetry allow you to say that other forms don’t?

JAM: Poetry came to me as a total surprise, an unexpected gift. Until I wrote my first “real” poem, I had never written any poetry other than doggerel. As you know I’m also a painter, and the inner experience of writing poetry is not unlike that of making paintings. In my artwork, an image appears to me, in my mind’s eye, and I sketch it out as soon as possible so I don’t forget it. It comes to me complete, in full color. Then it’s up to me to bring it to fruition on the canvas or the heavy paper I like to use. The poems that eventually added up to “Domesticity” came to me in a similar manner, but rather than images appearing in my mind’s eye, words appeared—sometimes in complete verse—in my mind’s ear. Because my poems are so stripped down, they allow me to get to some essential truth in just a few strokes, and approach subjects that I can’t get near in my longer work, because when I try, I get tangled in the muck and end up writing muck. But somehow in the compressed form of poetry, the way it hints towards rather than explicates details, I can. In a million years I didn’t think I’d ever publish a book of poetry.

YZM: Let’s talk about the title—why Domesticity? What importance does this concept have for women in general and Jewish women in particular?

JAM: I have a good friend who is a kick-ass Jewish, feminist artist. She was just telling me that it annoys her that when there’s a big event that involves food at our synagogue, it’s almost entirely women who volunteer for kitchen-related duties: shopping, cooking, and cleaning up. As it turned out, I had just signed on for clean-up duty for an event that required a lot of volunteers. But I don’t mind cleaning. In fact, I find the ordering and arranging of actual physical interiors satisfying: I like making a bed look beautiful; likewise a table; I like arranging flowers; I love gardening, putting things in order, arranging cookies on a beautiful old platter that had once belonged to a great-aunt. More than once I’ve painted patterns on my walls, making a kind of painted wallpaper. I can’t imagine having to go out into the world and making my way there, pushing up against others, competing. “I like the domestic realm.” I’m quoting from my own poem. Not everyone does. But I do.

For most of western history, women’s place was in the home (or working in someone else’s home, or in the fields, depending on economic need.) We were largely dependent on men to keep us fed and clothed, and didn’t enjoy anything like the agency we now do. Jewish women’s history was no different: we married, had babies, baked bread. Then birth control and feminism came along and we had choices our grandmothers and great-grandmothers didn’t. This is not news. My own hunch is that the old roles —women at home, men out in the world making a difference—doesn’t much entangle the majority of American Jewish women, including many Orthodox women. But for the very Orthodox—Hasidim, Haredi— there’s more pressure to assume traditional female domestic roles. For some the model works; for others, not so much.

YZM: What about the poems with explicit Jewish content, like “Tishrei” and “Kohelet”—do you see them as a form of spiritual expression?

JAM: Yes. But I view all of my poems as spiritual expression. Come to think of it, more often than not I experience all forms of creative art as spiritual expression. Where did Monet’s lily pads, Picasso’s Guernica, Tolstoy’s “Master and Man,” Singer’s “Enemies: A Love Story” come from if not from the Divine?

YZM: Sex and death are two themes that run through these poems; how are they linked?

JAM: Freud has a lot to say about sex and death, but I’m afraid that other than claiming that sex and death (and eating and pooping) are a part of our physical, rooted, embodied lives, I have little to say on the subject. For me, the subject of sex is tricky and weird, and at the end of the day, all I know is that for me, marriage was and continues to be the container, or if you like, the vessel, for that part of me. Death is—well, it’s death. My mother died of cancer twenty years ago, and her final illness coincided with my own bout of cancer. I was living abroad at the time and didn’t tell her that I was sick until I was back in the United States, and could no longer avoid the subject, since I was still pretty bald from the chemo. She said: “You were right not to tell me then. But I’m glad you told me now.” She then asked my husband to make her a double bourbon on the rocks (she claimed that bourbon kept her alive.) Six months later, in the Hebrew month of Shevat, she died.

YZM: “The Pact” is a concise yet powerful exploration of marriage; can you say more about the complicated nature of married life?

JAM: I can try! My husband and I are celebrating our 35th wedding anniversary this summer, and yes, it’s a long-haul project. You have to give up the part of you that wants it your way—both in terms of how to do things and in terms of psychological willfulness—and I did not want to do that. But who said life was supposed to be easy?

YZM: The death of self is such a bore, is one of your intriguing and memorable lines; what did you mean by this?

JAM: That line comes at the end of a stanza in a poem about psychotherapy. Over the years my husband has claimed that he didn’t know how anyone could be a therapist, and listen to all that—stuff. So the line in part refers to the outpouring of the story-of-self, the stories we tell ourselves and can get trapped in to our detriment. On another level, my entire adult life has been a quest to reclaim parts of my true self—the self I came into the world with, the equipment that God bestowed on me—that had been chipped off, resulting in decades of anxiety and depression. For others the “death of self” might mean drug or alcohol addiction, self-harming behaviors, anxieties, and even suicide. My own belief is that even for those of us (I include myself here) who are blessed with freedom, education, good health, and more than enough sheer physical bounty, learning to live in the light requires a lot of work and a whole lot of faith.