Looking Back: Jewish Lesbians Connect Across Generations

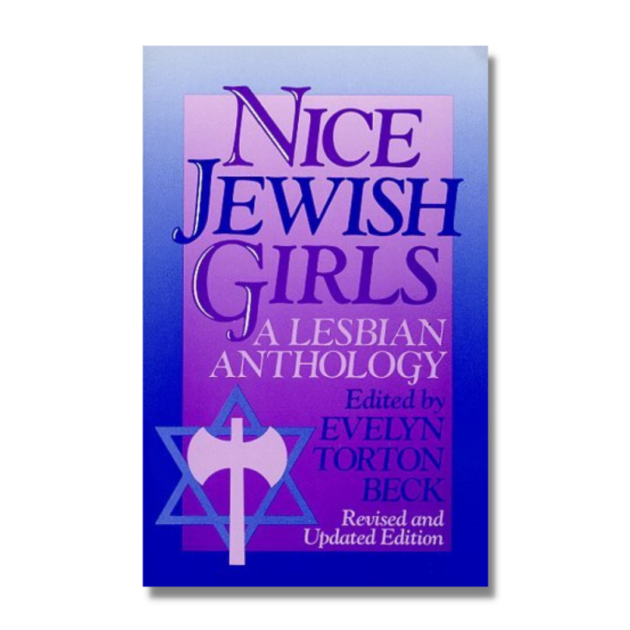

Evelyn (Evi) Torton Beck has advocated for the complex intersections of lesbian and Jewish identity in her work and activism for decades—from being a founding member of Di Vilde Chayes, a Jewish lesbian feminist collective, and later editing Nice Jewish Girls: A Lesbian Anthology (recently reissued and available to purchase in print or as an eBook on Amazon) in 1982, to developing the Women’s Studies program at University of Maryland, College Park. She’s also a longtime Lilith contributor.

Lilith intern Alexa Hulse, who has been profoundly impacted by the work of Beck and Jewish lesbians everywhere, discussed what it means to be a Jewish lesbian, then and now with Beck–in a two part interview. Read Part II here.

AH: You’ve been doing this work for a long time. When and how did you come to see your Jewish and lesbian identities in relationship with each other?

ETB: Coming to a deeper consciousness of what it meant to be a Jew was a process that started almost as soon as I came out as a lesbian in 1975. When I came out, I quickly became visible, working to “normalize” lesbian identity, to fight against homophobia, which in those years was very, very risky. Lesbians lost jobs, were rejected by family and friends, lost custody of children, were declared mentally unfit, in some states could be jailed, among other atrocities. Many lesbians remained in the closet, and in spite of our numbers among feminists, remained invisible. Although I was only an assistant professor without tenure, and my job was at stake, I felt compelled to speak out and try to change the world by educating the public whenever and wherever I could.

Each time I spoke about the issues of homophobia in Jewish communities and antisemitism in lesbian-feminist communities, my identity as a Jew intensified.

Even while I was sticking my neck out as a lesbian, thinking I was acting on behalf of all lesbians, I became aware of antisemitism within lesbian-feminist communities (I am not suggesting it was worse among lesbians, but that was where I was spending my time). Ignorance of Jewish history and culture was a large factor as well as unexamined antisemitic stereotypes. This recognition was a big shock as I believed I had found a safe “home” among lesbian-feminists, a place where I could be all of who I was. To my dismay, I quickly discovered that lesbians were not safe in Jewish communities either, which, like the dominant culture in which they were located, were homophobic and saw same-sex desire as “abnormal” and not appropriate within Judaism.

When my mother asked her rabbi what to do about my being a lesbian, he told her it wasn’t possible that I was one. It became my mission to raise awareness of what I had experienced in each of these communities as well as in Women’s Studies. Each time I spoke about the issues of homophobia in Jewish communities and antisemitism in lesbian-feminist communities, my identity as a Jew intensified.

AH: Has your identity as a Jewish lesbian evolved over time?

ETB: I don’t think that my identity as such has changed at all, but what has changed over the years is the inner sense of comfort with my identity, of knowing who I am in my bones, so now I don’t actually think about it much. I often forget about it, in contrast to the early years, when, after coming out, I was aware of my identity as a lesbian almost all the time. Lesbian was such a terrible taboo, most people found it difficult to even say the word (in Women’s Studies classes I assigned students homework to find places to say the word Lesbian aloud several times and note what happened in the exchange and how they themselves felt about it). Jewish lesbian was even more taboo. My gradual “forgetting” was made possible by the gradual erosion of homophobia in many (by no means all) places, and greater legal and social acceptance of same-sex relationships.

AH: What is your favorite thing about being a Jewish lesbian?

ETB: It’s a good question, but a little hard to answer since the feeling can be a bit amorphous, easy to intuit, strong to feel, and hard to articulate in language. I will try.

I like the feeling of being both insider and outsider at the same time in the different communities. I love the fact that there are things you don’t have to explain about these intersectional, overlapping identities. There are experiences we understand immediately, viscerally, with the body, things we don’t have to explain when we are together. But having said that, I am aware of the fact that even in a group of Jewish lesbians, there will be major differences — we do not necessarily share the same individual histories, do not necessarily agree on delicate topics. But we do share significant experiences that we find nowhere else in the same configuration.

AH: Young queer Jews like me are fascinated by Di Vilde Chayes (The Wild Beasts), a Jewish lesbian group you helped lead for a few years in the 1980s. What is your favorite memory from your work in the collective?

ETB: The feeling of a close-knit, like-minded group working together to forge something new was and still is, incredibly important to me. Entering unknown territory, moving Jewish from “margin to center,” to quote bell hooks, not knowing where it would lead us, was exhilarating. But most vivid and perhaps my most important “take-away” was a recognition that has become a kind of mantra for me and that I have tried to pass on to others. It was something Adrienne (Rich) said to me in the very early days of our coming together as a lesbian-feminist Jewish group. I am underscoring the Jewish, because that was the part that really scared all of us, but I thought it was just me. I said something like “I am afraid of where this will take me.” At the time I had no clear idea of what or why I was afraid—maybe that I would become religious? Join a synagogue? That’s funny, because now I am a non-religious member of two synagogues!

In retrospect I think my own fears had a great deal to do with my not yet faced the trauma of my childhood living during the Nazi occupation in Vienna, Austria and all that came after. In response to my statement about being afraid, Adrienne said, and now I have forgotten her exact words, but not their meaning, that “one is always afraid when you know you are doing something radical that threatens things as they are and are going to create change. And you know that the work will also change you.”

My other favorite memory is completely different. It has to do with the fun we had together and also points to one of my passions, of what I am doing these days—which is teaching Sacred Circle Dance.

One of our meetings of Di Vilde Chayes, which always took place over a long weekend, was at Adrienne Rich’s home (in Western Massachusetts where she lived with her partner, the writer, Michelle Cliff). After working hard all day on thorny issues, that evening we danced with abandon, joyfully letting go of our anxieties. Although Adrienne loved dancing, because of her rheumatoid arthritis she was not able to join us, but she loved watching us and she moved with us as best she could from a seated position. There was something very moving about what felt like a ritual of affirmation. Hineini! We are here!

AH: In your interview for Lilith’s Winter 1982-1983 issue you said that “In terms of the specificity of the [Jewish lesbian] history, we are just beginning to try to uncover it.” What is your favorite thing/event/person to have been unearthed since then?

ETB: Do I have to choose just one? I’ll start with Gertrude Stein even though she was not a feminist in the ways we think of today (although she was very aware of patriarchy and criticized it continually in her work), and although she was not out as a Jew, she did not hide it either. And her early poems in Tender Buttons but most especially the ones in the long Lifting Belly are among the most unabashed erotic poems. And she lived openly with a Jewish woman who was clearly her partner.

French surrealist artist Claude Cahun (French for Cohen, pseudonym of Lucy R. M. Schwob, 1894-1954) who very belatedly found recognition for her gender-bending, shape-shifting photographs, collages, writings, as well as her subversive work against the Nazis, who occupied the Channel Islands where she and her Jewish lover and creative partner, Marcel Moore (pseudonym for Suzanne A. Malherbe, 1892-1972) were living. Cahun and Moore were both imprisoned by the Germans but Cahun was especially weakened by the harsh conditions in prison.

AH: Do you see any connections between dance/movement, feminism, and Judaism?

ETB: Absolutely, not with the religion per se, but with Jewish culture. Sacred Circle Dance is a practice that brings in music and dances from many different cultures from around the world, and is central to my spiritual practice. Among the dancers, I am out both as a Jew and a lesbian and that feels very nourishing. The fact that we dance in a synagogue space is very important to me. By dancing together we intend to integrate mind-body-spirit and create peace, love, harmony in a sustainable world. We connect our dances to what is happening in the world around us.

As a traumatized child refugee who had escaped life-threatening danger, dancing was a great comfort and today, given Covid and so many other frightening aspects to our world, which I probably don’t need to spell out, it still serves as that. I have also offered workshops such as, “Inspiring Activism for Social Justice and Ecology through Sacred Circle “ which I see as part of my contribution to Tikkun Olam.

Get to know your histories, Jewish, lesbian/feminist and welcome all the ways they may open you. Get to know old Jewish lesbians, and listen to their stories. Let the being together with other Jewish lesbians be a cause for joy.

AH: What advice would you give to young Jewish lesbians?

ETB: I would urge young Jewish lesbians (hopefully they are also already feminists but if not) to read some of the founding texts (Sisterhood is Powerful) and take its teachings to heart as they will sustain and nourish you. Many of the women who created those early texts were Jewish, but not identified as such, either by others or themselves. That is what Joyce Antler’s book (Jewish Radical Feminism: Voices from the Women’s Liberation Movement) tried to bring to the fore — the degree of Jewish women’s involvement in developing second wave feminism, including Jewish lesbians.

Find community or create it. Find allies. But remember that even within Jewish-lesbian groups, there will be differences of all kinds, too many for me to spell out here, even if they are not all visible. Let your differences be spoken and respected. Learn from each other, teach each other, and learn to work together across political and other differences. Learn about deep listening. And allow your identity as Jewish lesbians to be wide and inclusive.

Take into account other oppressions that might be present even within your own group. Learn to recognize external as well as internalized antisemitism when/if it arises. Do not be afraid to name it, work against it in yourself and speak out against it publicly. Find allies among others, find those who will support you in your daily life. Get to know your histories, Jewish, lesbian/feminist and welcome all the ways they may open you. Get to know old Jewish lesbians, and listen to their stories. Let the being together with other Jewish lesbians be a cause for joy.

Alexa Hulse (she/they) is a junior at Hollins University. She is pursuing a degree in Gender and Women’s Studies and enjoys iced lavender lattes and the moon. Alexa is Lilith’s current social media and archival intern. You can find her in “Salt and Honey”, an anthology from jGirls+ Magazine, and on Instagram @alexabhulse and @t00.soft.