In a Parallel World, Tweens and Moms Still Disagree

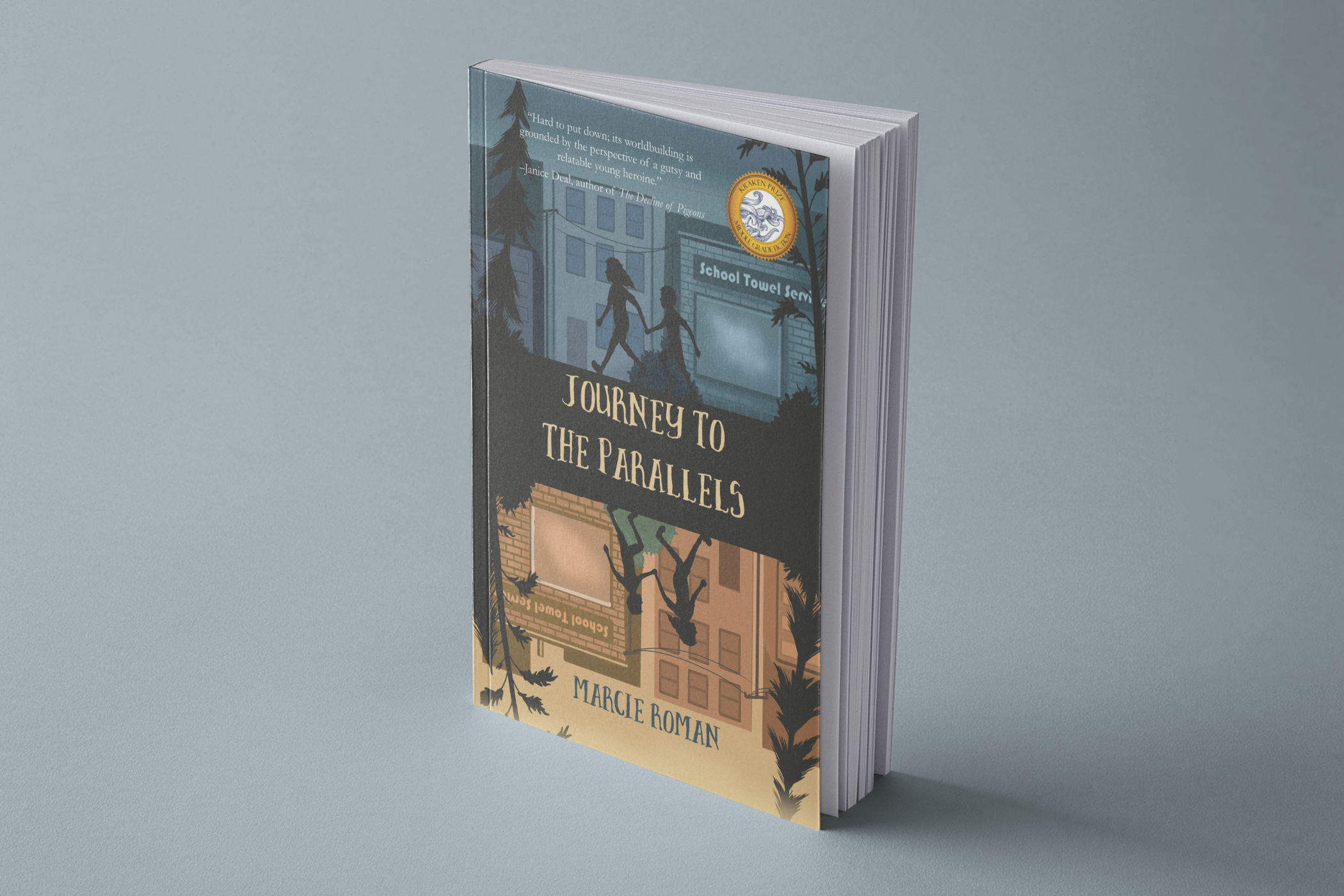

rgueTwelve-year-old Amber has the ordinary problems of a seventh grader: strained friendships, an annoying younger brother and, ugh, why can’t her unconventional mother just act normal for once? When her wish comes true, Amber suspects it’s not just her mother’s behavior that’s changed, but her actual mother! The only problem is that she doesn’t know where her real mother went and she’s determined to find her. This is the off-beat premise of Journey to the Parallels (Fitzroy Books, $15.99) and debut novelist Marcie Roman talks with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about what it’s like to travel to an alternate universe, and what the experience can teach us about our own.

YZM: You’ve said the plot explores ideas of Tikkun Olam; how does it do that?

MR: While I never know what I’m writing about until I’ve written it—my early drafts would be much cleaner if I did!—it became clear as the plot of the novel emerged that I was asking questions about how to parent children toward being civically engaged, especially when it comes to being aware of and responding to acts of oppression. The characters in the book—a single mother and her two children—venture into a parallel world that’s even more broken than ours. They’re compelled to identify what’s gone wrong and then find the courage to stand up to injustice, while navigating the tensions that exist within their own interpersonal relationship.

At the start of the novel, Amber, the twelve-year-old protagonist, only wants to fit in and have the things her friends have. Through her adventures, she and her younger brother gain a greater understanding about the benefits of being an individual thinker, the value of civic engagement, and how even small gestures of kindness and empathy (along with a dose of humor and imagination) can effect positive change. The book doesn’t suggest there are any easy solutions, but it does encourage readers to ask questions about why things are the way they are, and to look for ways that exist within their daily lives to bring about a more just world.

More broadly, I view the act of reading novels—which these characters enjoy as well—as a vital part of that healing process, in the way that fiction can enhance readers’ compassion and empathy by letting them experience what it’s like to be another person or face a different set of challenges.

YZM: You’ve also said the novel has a feminist theme; can you talk more about that?

MR: When I wrote the book in early 2016, I was motivated by questions I’d been having as a Jewish feminist mother trying to parent an independently-minded tween daughter. This was happening against the backdrop of the presidential primaries, which had me considering a lot of “this can’t happen, but what if” scenarios. (Flash forward six years, and too many of those “what if’s” have edged closer to reality.)

From that emerged a sketch of a patriarchal government that enforces a traditional set of values on its citizens, forcing women and girls into an inflexible container of “this is how you need to be…or else.” While this theme of gender equality has been appearing in adult books as well, in this novel, two of the ways it plays out are that single mothers are placed under strict surveillance and girls no longer play sports (partly due to a lack of Title IX protections). For Amber, these challenges propel her toward self-empowerment and finding her own voice. Although this happens within the framework of a sci-fi/fantasy adventure, at its heart, it’s about a mother and daughter working to accept each other’s unique way of being in the world, while looking for ways to support the rights of all women and girls to do the same.

YZM: Is the fact that Sandra, Amber and Beetle are Jewish play a role in who they are?

MR: While the family is secular, I do think their heritage contributes to the way they approach the world. Although Amber, like many tweens, feels embarrassed by her mother, she and Beetle share their mother’s tenacity, grit, and sense of humor; traits I’ve always associated with my Jewish roots. They’re willing to ask tough questions and look for nuance in the answers. I think it also expresses itself through Sandra’s sense of purpose, and her way of viewing others with kindness and compassion. And of course, in writing these characters I drew heavily from my own experiences as a Jewish woman.

My stories have also grown from the creative compost of Jewish writers I’ve read, starting with Sydney Taylor, Judy Blume, and EL Konigsburg, and later on through my discovery of Tillie Olsen, Grace Paley, Cynthia Ozick, Deborah Eisenberg, and so many others, who let me see the myriad ways Jewish values and culture can emerge on the page.

YZM: What’s the definition of a good mother? How does Sandra rate? Did your own life as mother or daughter inform her character?

MR: When it comes to parenting, I don’t think there’s any one label or definition, since so much is based on individual needs and circumstances, and whether there’s a co-parent or if one person is carrying the full weight (both emotionally and financially). And, as the book demonstrates, it can be easy to fall into judging those who are taking different approaches. The historic lack of support in this country doesn’t make the role any easier—and culture of course is always presenting new forms of judgement. Even women who elect, as is their right, to not have children, can still face similar challenges in their attempts to serve that role for an aging parent, or community member, or for a young person who just needs a caring adult to listen.

One of Amber’s main issues at the book’s start is how much her mother deviates from the norm as established by the mothers of her friends. Sandra can’t cook, dresses in an unconventional style, and will pontificate about matters close to her heart like political engagement and animal rights. But when Amber gets her wish to have a more conventional mother who adheres to the stricter culturally acceptable norms, she gets a rude awakening.

While I can only speak from my personal experience, my goal in parenting (and daughtering!) is similar to Sandra’s: to offer unconditional love, respect, and kindness, and to listen and provide comfort when things get hard. I’ve also found a sense of humor and keeping an open mind helps, as does a willingness to adapt. And to acknowledge when mistakes are made (because I make them often!) On that note, one of the greatest gifts I got from my parents was being granted the space to make and learn from my mistakes, and to know that no matter what, I belonged, even when I wasn’t feeling that way in the larger world. I think that desire to communicate that to my children was one of the guiding questions in the book. It helped me approach the characters not just from my perspective as a mother, but to re-engage with my attitudes and anxieties from when I was that twelve-year-old wanting to exert my independence. Like Sandra, I’m messy and flawed, but I know that I’m always acting out of love, and trying to point my parenting compass toward that sense of unconditional acceptance.

YZM: Can you talk about the idea of a parallel world and what it suggests?

MR: Growing up, I loved reading portal stories and was always trying to walk through closets or wishing Mrs. Whatsit would knock at my door. So I think at a young age I was primed to view the limits of what we see as reality as iffy at best. When I first heard about the more scientific underpinnings of the multiverse (that idea that anything and everything that could happen is happening simultaneously), I was eager to dive into the research. But even more so, I wanted to imagine what it might feel like to travel between those worlds. Because I also believe that moment by moment we’re creating new versions, and we can either take them closer to our vision, or let fear, including collective fear, get in the way and veer us more off-course.

When I wrote the novel, I had no idea how much our own political world would take on that surreal feeling of “am I in a parallel world?” To stay engaged with the book, I had to tell myself, in those early dark days, that maybe we were now the ones living in the parallel world, and Amber’s family had come from one that wasn’t nearly as off-track. But, the other thing that parallel worlds help me consider, is that everything can and will change. Then, the real challenge becomes, what can we learn from these other potential iterations to better direct our actions toward creating the one we most hope to inhabit.

Stories in a way are always transporting us into parallel worlds, even when the worlds contained look a lot like the one we think we know. And not to get too philosophical, but we’re each, in a way, traveling through our own parallel worlds because our individual perception is tied to our unique vantage point, experiences, and filters. So one other lesson, that ties back into Tikkun Olam, is to try to always remember that, and then look for commonalities (those shared features that link these parallel worlds). The other day I was driving on the expressway, and I saw some bumper stickers that I didn’t agree with, and thought, well one thing we can all agree on right now is that we all want to head North.

YZM: What do you hope your (young) reader will take away from this story?

MR: To me, reading and writing are two sides of a conversation, so I hope that young readers can see themselves as participants in the reading experience, and at the same time enjoy the immersive state of being caught up in the book world. As a child (and adult) bookworm, one of my joys has always been to feel so excited after finishing a book that I’ll find myself thinking about it well after the last page, while also eagerly searching for the next book to dive into. On that note, I very much wrote toward capturing the magic of the books that I loved growing up and that I still go back and re-read. Probably the greatest gift for me as a writer would be if a reader felt inspired to try writing their own story. (My earliest writing attempts came from being in conversation with Shel Silverstein poems.)

More directly, perhaps the story will encourage them to consider their individual attitudes about the themes in the book, so they can try to answer not just What do you think, but Why do you think it. Then maybe the next time someone tells them they should like this thing or shouldn’t like that thing—or, this person but not that one—there’s a pause to self-reflect on all the various positions that can exist between that polarization of “like” and “don’t like.”

And then, finally, even though they aren’t of voting age, to recognize that they can already exert power at the voting booth by encouraging adult members in their lives to go vote!