A Love Affair With Barthes’ Words

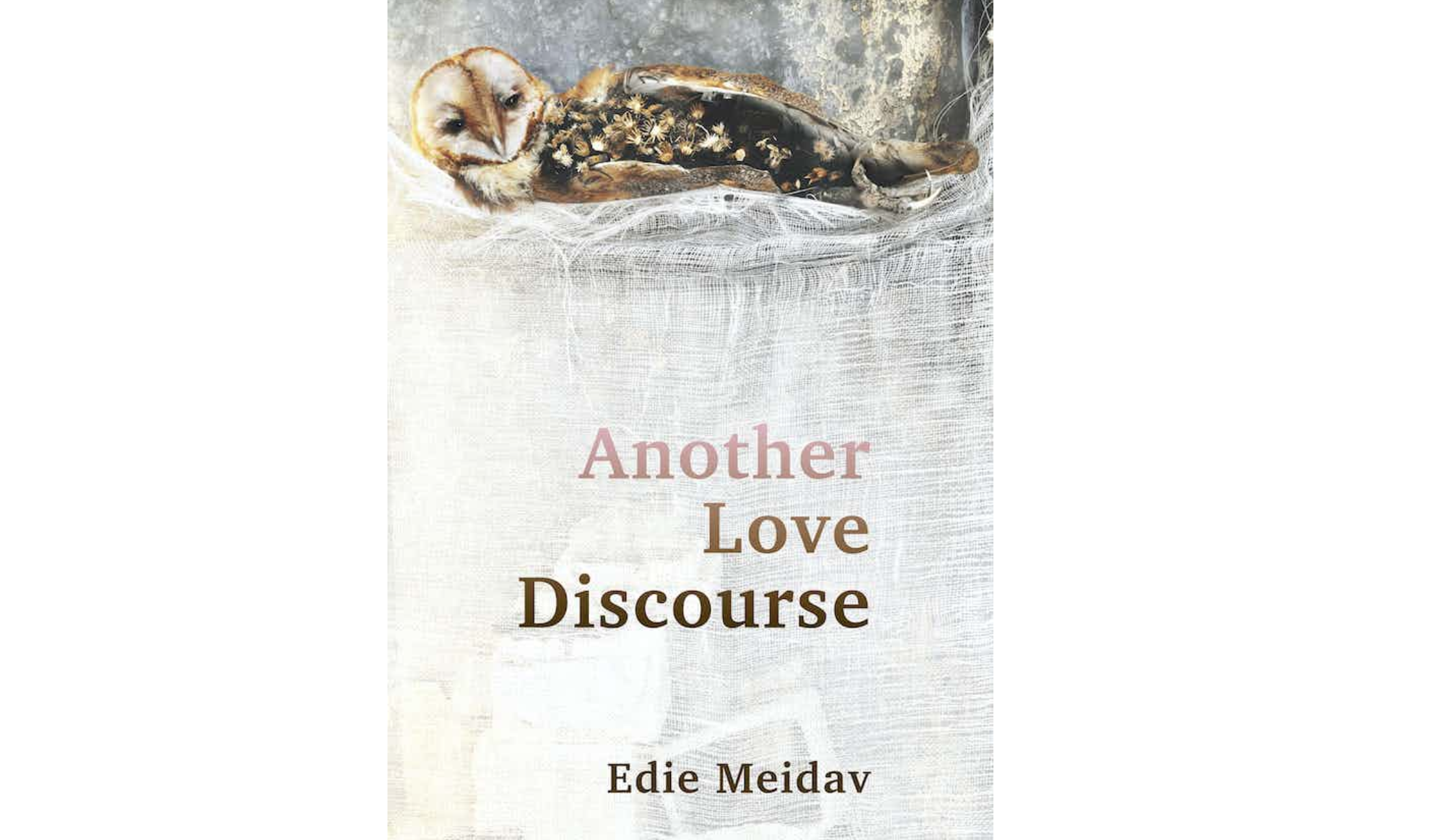

Caught in the cross-currents of a fraught divorce and a new love, the death of her mother, and a global pandemic, a woman delves deep into an obsession with the work of 1960s French philosopher Roland Barthes. Her struggle to make sense of his work and life—as well as her own—form the basis of Another Love Discourse ($23.95, MIT Press). Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks to author Edie Meidav about her unique and transdisciplinary novel.

YZM: What was the inspiration for this novel and why did you choose such an unconventional structure?

EM: Years ago in L.A., straight out of college, I had a boss, the late Rachel Rosenthal, a sixty-something-year-old with a great bald head, a beautiful throaty accent borne of her Parisian childhood with a father who was a pearl trader, somoene never without an unusual animal companion and a singularly wild performing and teaching presence. Prescient, she was dedicated to environmental performance art, and yet also had the kind of past which makes another era seem so colorful and optimistic if blindered: she was mate to the first McDonald’s clown, a pal to Jasper Johns, John Cage, and Merce Cunningham. This Rachel, early in our time together, having hired me straight out of college, essentially, to be her manager, anointed me with this dictum: you are like me, you are another gay man in a woman’s body. (And while this novel is no memoir, no autobiography, at a very few points it does steal from my life, and so you will see this line quoted in the book itself.)

As the pandemic began curling over all of us like some kind of angry wave, I was teaching graduate students in the MFA at UMass Amherst this particular book: A Lover’s Discourse, the wonderful, importunate work by literary critic Roland Barthes, who came of critical age in the 60s and 70s, in which he creates an unusual taxonomy regarding desire, whether or not desire is symmetrical or other.

People have asked me if I was a long-time Barthes scholar—hardly the case, yet I had always loved him. For one thing, how he came at an angle toward literary texts and then did a kind of ice-skating twirl away. He creates such impassioned schema right next to any text (everything is a text for Barthes). In him you find the hunger for whimsical order known more often by the artist than the literary critic.

How many beautiful lines are there in his work! And if you happen to be reading this and stumbling across him only now or with renewed interest, do please start with Mythologies, the first book that pulled me in, a curated collection of his articles for a French journal, where you will find lines such as:

-The picturesque is found any time the ground is uneven.

-Justice is always ready to lend you a spare brain in order to condemn you without a second thought.

-The cultural work done in the past by gods and epic sagas is now done by laundry-detergent commercials and comic-strip character.

Right there in the blinding white heat of the pandemic, I found myself suddenly coordinating a household of some seven beings; you could say that Barthes entered my memory with his voice both so heated and cool, the categories of his A Lover’s Discourse offering themselves up like such a beautiful antidote to the domestic entropy of our life under shutdown.

I found myself fleeing the entropy for my writer’s shed, out back in some snarl of woods, and taking one of his categories (you’ll see the book has many) or inventing one of my own, and writing to it of this work that became a novel, about a woman impassioned by Barthes struggling to keep her family afloat. In this way, slowly but also all at once, Another Love Discourse amassed.

YZM: So how did you manage the actual writing?

I would write daily prompts, for survival, each day. As winter became spring, it happened that one single tick bit me, yet I did not treat the bite well, and, as you may have heard, climate change is upon us, meaning that all the melting northern latitudes allow more pathogens to survive winter and reach us via any vector old or new, which means that the prevalence of Lyme disease has increased in New England where I live.

Without knowing, then, writing on Barthes, I succumbed to severe neurologic Lyme, unaware of the extent of its devious work until half my face froze. So this book was written, most of it, with a strong sense of mortality, a sense that my brain was dying, against our collective sense of doom. As some of us have epigenetic trauma deep within our marrow (see Elizabeth Rosner and so many on this), the feeling of an end felt quite imminent. Further, I had lost my mother at the beginning of the pandemic, and (again, this is a novel, so truly departs from my own biography) was living in a new post-divorce reality. For all these reasons, Another Love Discourse became my attempt to shine light into questions of love and attachment, to figure out what really mattered in what was, then and perhaps continuing into this moment, a truly shadowed time.

YZM: What did you mean by the line, “…a Jewess who rarely outs herself”?

EM: Perhaps it is not wholly accurate but may have to do with our current resurgence of antisemitism. I was always proud of my Israeli diasporic father that he did not hide his religion, yet I have found myself—thinking of Joyce’s maxim that the writer works in silence, exile, and cunning—sitting at, say, French dinner parties, hearing people talk in a strongly antisemitic manner and, because I mostly pass as something else, trying to learn all I can about prejudice, a bit in the manner of the New Yorker writer Rich Benjamin, author of Whitopia. Further, because I teach in the current academy, and yet have an obviously Israeli name, the family going back to someone named Yohanan the sandalmaker back in 2nd-century Palestine, I have found myself not leading with my identity so as to make space for others.

YZM: Let’s talk about the illustrations, some of which you did.

EM: Increasingly, I have loved collaboration, and to work with the Dutch artist Cecile Bouchier, whose work is the main act of the illustrations, was a joy beyond compare; she had some work toward which I wrote, and yet sometimes I would ask her, say, to come up with an image of a wedding dress, and we would work together. In college, I was a painting major and later an art critic, briefly, so to get to work in an interdisciplinary manner formed one of the great pleasures of this book.

YZM: This is a novel of mothers and daughters at its heart.

EM: Long ago I found that my tribe of friends all seemed to have been touched in some way by some mother wound; at times I have called this the motherless daughter, but in my case, this is not true; my mother rallied to become my mother especially after I turned 21 and came home for a bit from my Eastern college, and we had a sweet relationship for this last chapter of her life. What endlessly fascinates me is the way our earliest imprints of attachment—Winnicott, also referenced in the book, said it best—play out in so many spheres until we get the spiritual lesson we are supposed to get. In my case, it took me many years to believe that I could truly relax in the embrace of the beloved, that I could trust someone fully. This book is, then, in so many ways, about the ways we seek love and attachment beyond ourselves until we are able to touch that vast love we all have within.

YZM: You’ve asked, Why is it some women know how to keep their physical space so orderly? What is the relationship between women and order, both internal and external?

EM: What a wonderful question! Sometimes in my own craving for order, I have felt that order is a mother, the thing that offers and provides reassurance. Every infant hopes for that regular heartbeat. Perhaps those identifying as women learn a socialization that, with its complaisance and empathy, can manifest in a hypervigilance about the external world in its granularity, structures, divisions, boundaries. You can tell so much about people by their entry halls, their sock drawers, their medicine cabinets, isn’t that the case? We can see one another’s hopes for how we live among others in this world, how we comfort ourselves, who we hope to be or become, and what we wish to hide away, believing that we cannot be loved if we show ourselves fully. Perhaps this book, which has occasioned a truly different response than any of my previous works, is an offering toward others dreaming of feeling that love can exist in so many hidden pockets in our world.