“Young Girls Are Hotbeds of Trauma”–Talking to Playwright Stephanie Swirsky

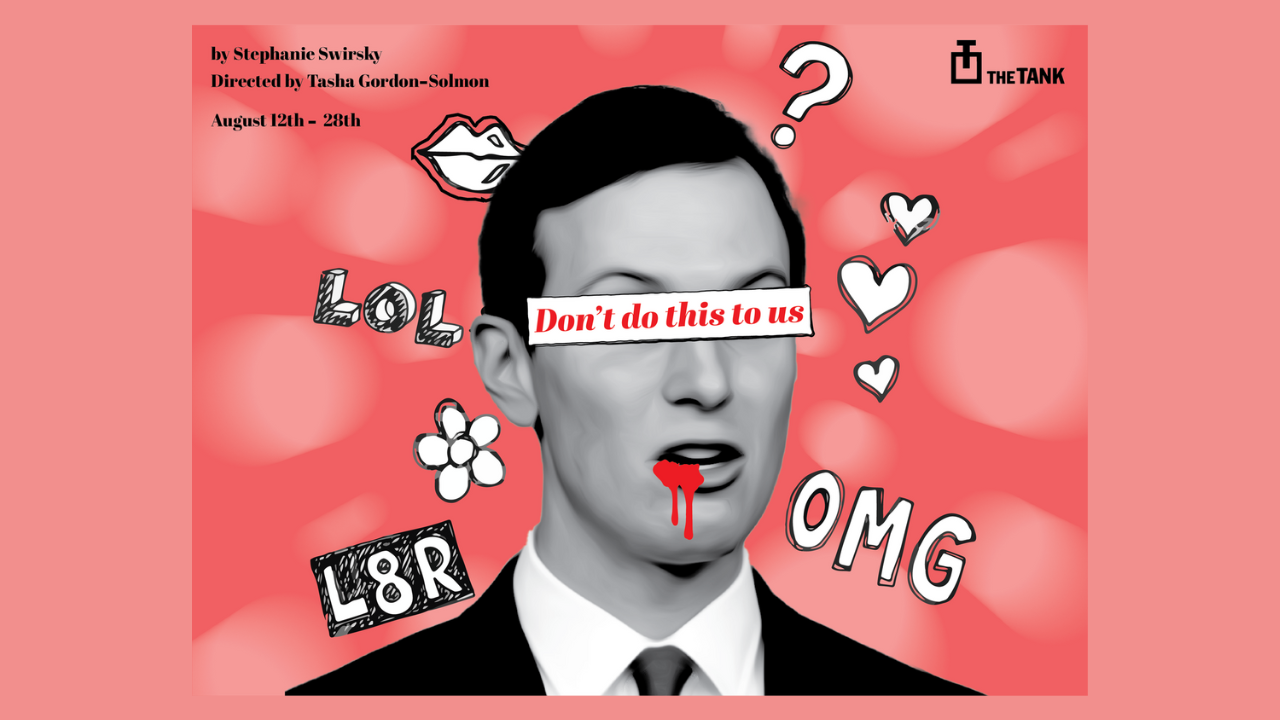

Playwright Stephanie Swirsky’s play Don’t Do This To Us is hard to describe. Technically, it’s about a girl named Rachel who falls through some kind of Shabbas time-hole and finds herself in exactly the situation she purportedly wished to be in: at a Jewish youth event with Jared Kushner—yes, that Jared Kushner—whose dick she would like to break. It’s weird, yes. It’s funny, yes. But it’s also ridiculous and terrible and painful. As the character of Rachel ventures deeper into the 1990s with a gaggle of girls and a young Jared who quotes Margaret Thatcher and refuses to discuss money on Shabbas—but will discuss buildings!—she’s ultimately upset by her own machinations and loses her own train of time-traveling thought. “Rachel is my anxiety spiral,” Swirsky explains.

Like Kushner, Swirsky grew up in New Jersey: “I definitely felt like I knew him, even though I didn’t.” She, too, was involved in Jewish youth groups—USY, in her case—but how did the idea to break his penis come to mind? And why? “It was right around the time that Trump got elected,” Swirsky explains. She was on the phone with a friend, complaining about the confirmation bias of antisemitic tropes that are overfamiliar: “Jews have a lot of money, and money buys them power. Jared embodies that in a very obvious way… how do you take that power away? You can’t take away his money…”

Meghan Finn, the artistic director of The Tank, chose the script because, “the writing is as relevant as it is humorous and idiosyncratic. She isn’t afraid to follow a whim and pulls no punches.” When the character of Rachel finds herself romantically entwined with Jared, the conversation turns absurdly towards teen questions of intermarriage and Fiddler On The Roof and the Holocaust at which point Rachel haplessly admits: “Why does talking genocide turn me on, I have so many problems.” Swirsky doesn’t shy away from hard topics in our conversation either. “I’m obsessed with the Holocaust because I don’t have an answer… it’s an unspeakable trigger that you are trying to mind, especially as a white Jew.” Especially as a white Jew. If you can assimilate, why don’t you? Why remind the world that you’re Jewish? ‘Cause you have to do Shabbas? Why can’t you eat pork? Just eat pork. Navigating those things actually does relate to the Holocaust.”

Antisemitism has loomed for Swirsky both internally and externally: At her first job in a small advertising agency in New York City, a coworker rolled up in his chair and let her know he’d be dressing up as a Jew for Halloween with a black hat and curls. The next day, he explained to her that Jews run the world, quoting statistics at her; she disengaged and denied the premise. Later, he patted her on the head and called her “a good woman.” When she finally reported the incidents to HR, her list of antisemitic incidents fell on deaf ears, but when she mentioned the patting and “woman” comment, jaws dropped.

But the demons lie within, too: Swirsky grew up in a family that was ambivalent about religiosity. Her father was culturally Jewish, and her mother was more observant, insisting on keeping kosher and Shabbas. “There was already a battle in my home.” Swirsky strongly identified with what she calls “insular Conservative Jewish stuff.” When she attended a high school with few Jews, she “I was considered ugly in my high school and attractive in my Jewish youth group. I learned how to present in different ways… that’s my internalized self-hatred. Young girls are hotbeds of trauma.”

The play’s currently running at The Tank in midtown, an important incubator of edgy downtown theater. It adheres closely to the mission of her theater, according to Finn: “I like to think this play couldn’t happen anywhere else for it’s first run—it’s daring and hilarious, exactly the kind of work I love to bring here.” And because the play is so current, audience members sometimes ask Swirsky what the message is. She’s very sure of her answer: “There is no message. I don’t have the answers. I’m more interested in the conversations people have. I, as a writer, have no need to control people. Besides, that’s a terrible way to go into artistry. I want people to engage with the work.”

At the end of the play (not a spoiler, I promise!), a Jewish song called “Nachamu” is heard, and Rachel continues babbling over it, grappling with her time-traveling choices. The full name of the song is “Nachamu, nachamu, ami” which loosely translates to “Comfort, comfort, my people.” The word “nachamu” can also be traced to another translation: regret. As Rachel ceaselessly processes and punishes herself and those around her, a character named Shira turns to the heroine and says, simply, “I really do want to just listen, Rachel.”

Don’t Do This To Us! plays through Sunday, August 28, 2022, at The Tank, 312 West 36th Street, NYC. For tickets, go online.