Continuing the Story of Ivanhoe’s Rebecca

In twelfth century Salerno, Kingdom of Sicily, a young Jewish woman named Rebecca, who will be familiar to readers of Ivanhoe, pursues her dreams by attending medical school. Practicing her profession, she defies family pressure to marry Rafael, the man who loves her. But even more pressing is the conquest of Sicily by the Hohenstaufens and the arrival of rogue crusaders, both of which threaten Salerno’s long-standing atmosphere of religious tolerance. When a rabbi is falsely accused of murdering a crusader, Rebecca and Rafael commit to pursuing justice and protecting the Jewish community—and themselves.

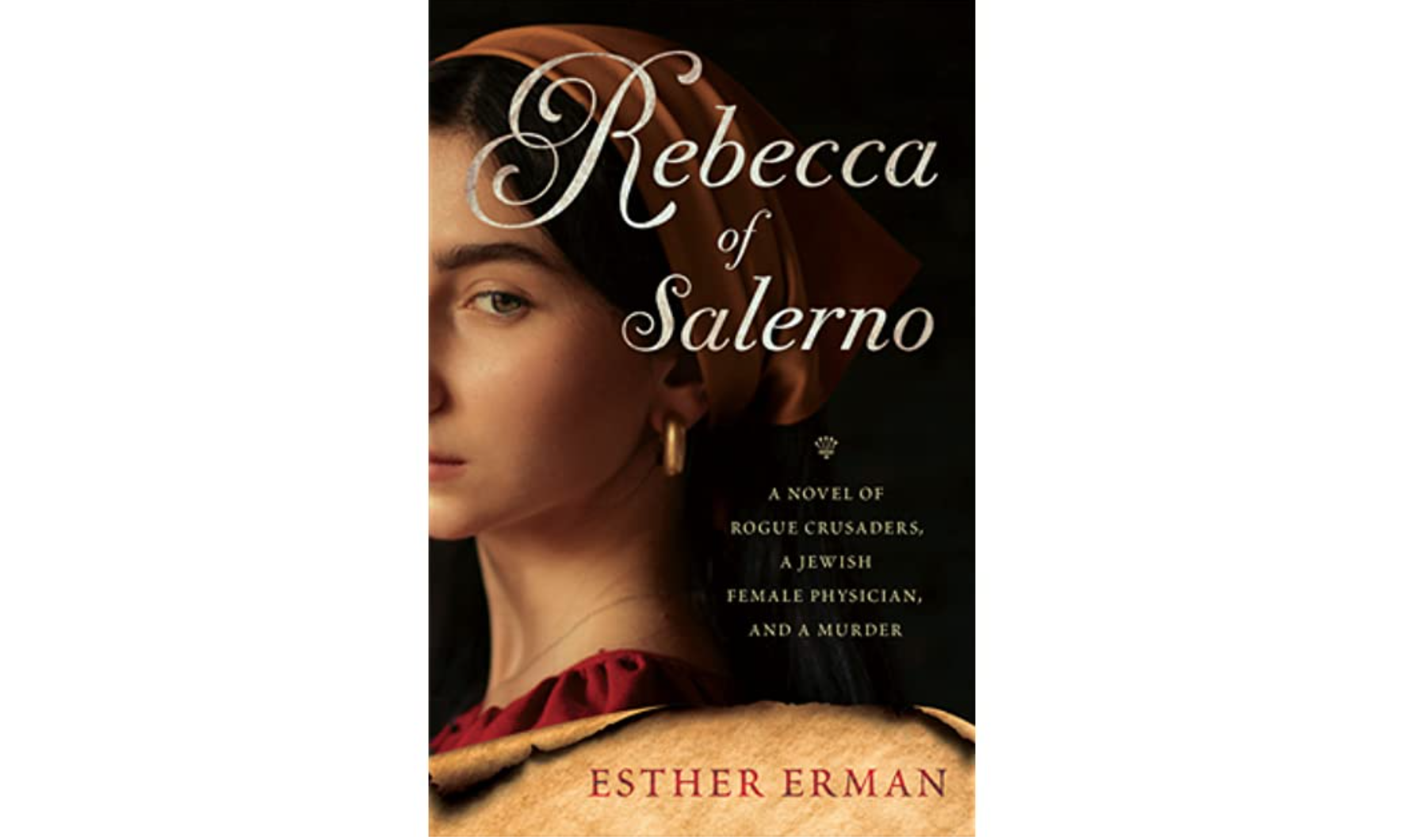

This is the setting against which Rebecca of Salerno (She Writes Press, $17.95) unfolds. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough chats with author Esther Erman about this fascinating period in Jewish history.

YZM: How did you come to be interested in this subject? What inspired you to write a book about it?

EE: My book is an homage to Sir Walter Scott for his creation of the character Rebecca in his 1820 novel Ivanhoe. I believe Rebecca is the first positive Jewish character in European literature. That achievement deserves to be acknowledged.

I discovered Rebecca when I did a survey of images of Jews in literature while writing my doctoral dissertation about the Yiddish language (Mame-Loshen, Immigrants, and the Holocaust: Yiddish in the United States, 1994, Rutgers Universtiy). Much as I loved the literature I read, as a Jewish woman, I’d needed to compartmentalize: mostly, Jews were invisible. And when they did show up, they were villains or otherwise negative characters. In the more recent parlance, I never saw myself in what I was reading.

And then came Rebecca: beautiful, brilliant, brave, big-hearted, and a good, faithful daughter! I became almost obsessed with her, reading Scott’s novel several times and also enjoying the story in other media. Scott, however, essentially abandons Rebecca at the end of his novel; if I was to know what happened to this still very young woman, it appeared my only recourse would be to write the story myself.

YZM: Is Rebecca based on a real person? How does Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe figure in?

This is a great question! There is no definitive answer. An urban legend has it that Scott based his Rebecca on the American woman Rebecca Gratz, whom he learned about from the American writer Washington Irving. Although there is no direct evidence to substantiate this, it is somewhat circumstantially credible because of who Gratz was.

Gratz (1781-1869) lived much of her life in Philadelphia. She was born to a prominent family, had a solid education, and never married though she appeared to have (somewhat similarly to Rebeca) a romantic relationship with a Christian man. Gratz was especially known for her charitable work—for orphans, for education, for women, and more. She did know Irving and other literary figures of her time. The basis for the supposition was that Gratz very much impressed Irving with her kindness and skill when she helped to care for Matilda Hoffman, Irving’s beloved fiancée, prior to that woman’s early death. In 1817, Irving actually did visit Scott at his home in Abbotsford, in the Scottish borders. At that time, Irving was supposed to have sung Gratz’s praises, inspiring the Rebecca character. After writing the book, Scott was purported to have sent Irving a copy along with a note asking how he liked the Rebecca character and if she compared well with the original. Unfortunately, there is no record of the 1817 conversation, and the note has never been found. Gratz did read Scott’s novel, which she remarked she found most pleasing. (A good source for information about Rebecca Gratz is Dianne Ashton’s Rebecca Gratz: Women and Judaism in Antebellum America.)

As to Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe: I whole-heartedly recommend this wonderful story, which takes place in twelfth-century England, for its gorgeous writing, intriguing dialogues, and delightfully intricate plot twists and turns. Very briefly: Rebecca is in a love triangle with Ivanhoe and Rowena, whom Ivanhoe had earlier pledged to wed. Thanks to Ivanhoe, Rebecca’s father Isaac receives kind treatment when seeking shelter. Isaac, in turn, helps finance Ivanhoe to compete in jousts. Rebecca is drawn to this noble knight. After he is grievously wounded, she heals him. But, a Knight Templar falls in love with Rebecca and, when she spurns him, kidnaps her. His fellow Knights put her on trial as a sorceress, and she’s condemned to be burned at the stake. Still weak from his wound, Ivanhoe manages to save Rebecca just in the nick of time. The two young people have a moment before Rebecca and Isaac decide to flee the increasingly dangerous England. Rebecca has given her heart to her hero Ivanhoe. Disappointed in love, she vows never to marry and resolves to devote her life to healing. My book picks up her story from there.

YZM: Let’s talk about Jewish women who were doctors in the twelfth century—were there many? Was there really a school in Salerno that allowed Jewish women to train as physicians?

EE: Taking the second, simpler, question first: Yes, the Schola Medica Salernitana (Salerno), which lasted from the ninth to the nineteenth century, was a place where men and women—Jews, Christians, and Muslims—could study together in medieval times. Salerno, then a part of the Kingdom of Sicily, had a reputation for religious tolerance. The medical school was part of this atmospher. Unfortunately, the tolerance began to degrade after the Hohenstaufen conquest of the Kingdom late in the twelfth century. This historical change plays an important role in my novel.

As to the number of Jewish women who were doctors in the twelfth century, although precise numbers are unknown, there is much evidence of their not being uncommon. According to the British historian Cecil Roth [“The Qualification of Jewish Physicians in the Middle Ages”, in Speculum, Vol. 28, No. 4 (1953), pp. 834-843, The University of Chicago Press], Jewish women certainly provided medical care to their families and maybe to other people. Information about the training of Jewish physicians—male and female—in that era is not well-documented. There was a differentiation between the experiences of training for physicians in Christian versus Muslim lands. Salerno was, of course, in a Christian land. Some Jewish women could have attended the medical school at Salerno, though the rigorous academic requirements for admission would have been a barrier for many. Roth does point out that there was a title for Jewish women physicians—La Mirgesse. The existence of the title implies there were people who had the title.

The female who has been most famously associated with the Salerno medical school in the twelfth century is known as Trotula. “La Trotula” refers both to three twelfth-century texts about women’s medicine and the actual woman, Trota of Salerno, who wrote one of the texts. She was a physician, a medical writer, and a teacher whose texts were widely used in her era and have been rediscovered recently. There are no historical indications she was Jewish.

YZM: How did your own family history and experience inform the novel?

EE: Of course, in a large sense, one’s family history and experience informs everything. For me, my family and my roots inform all of my writing and much else in an ongoing reality that I continue to discover, explore, and try to understand.

Each of my parents was the sole survivor in the Shoah of their families in Poland. Each survived ghettos, slave labor, Auschwitz, and other camps. My mother was on the death march from Auschwitz and ended up in Bergen-Belsen. My father was in numerous hard labor camps. Following liberation in 1945, my parents met and married in a DP (Displaced Persons’) camp.

One anecdote that tells much about perennial Jewish experience and the unintended consequences of our decisions: My father had come from the city of Kielce, which is notable for having a pogrom and murdering dozens of Jews on July 4, 1946, “after” the Holocaust. My father wasn’t in their number because my mother, pregnant with me, wouldn’t let him join the other Jewish survivors from Kielce on their “visit home”. (My father always said, if he’d died, no one would be putting the number of dead at six million and one.)

I was born in Oct. 1946 in Stuttgart, Germany. We had a traumatic, storm-filled crossing to the US. Once in the US, we were housed in a rat-infested firetrap of a tenement on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. My parents had no support of any kind, which contributed to my mother’s lifelong depression—though, until the last seven years, she was very high-functioning.

I came to the US as an infant refugee. The greatest effects of the refugee status came from being a greener—a raw newcomer, always having an awareness of being alien and different in some way from “regular” Americans. My first awareness of difference amongst people was the languages they spoke. At age four, I knew I was a Yiddish speaker, but I wanted to become an English speaker. Though my parents continued to speak Yiddish to me, I stopped speaking it as soon as I learned English in kindergarten. (The language my parents did not teach me was Polish, which, in our house, was the language of secrets.)

I became a naturalized US citizen at age eight when my second parent—my father—was naturalized. I got my “papers” at age twelve, as we were preparing to go to Canada for a family gathering. I recently learned that, for my family’s first trip to Canada, when I was four and none of us were citizens, we had to have “Resident Alien” cards. So the US government still has a piece of paper on file somewhere identifying me as a “Resident Alien” with my four-year-old face looking up in a photo. In some ways, Resident Alien continues to be an accurate description. For example, one reason why I’ve never been to Mexico is that any time I’ve happened to be near the border, I haven’t had papers or a passport with me, and there was no way I was willing to chance not being allowed to re-enter the US.

Growing up in the circle of refugees who were my parents’ closest friends and relatives, at an early age I thought being in a concentration camp was a universal experience. Also, I would hear “Guess who’s alive?” in contexts where most other people would say “Guess who died?” And, as I became acquainted with American kids my age, I discovered that they had something wonderful that I did not have—grandparents! Why didn’t I have any? The response was traumatic. So were holidays.

I still consider myself a refugee, albeit an invisible one. I once compared notes with a Chinese woman whose family has been in the US for three generations. She resents being viewed as an alien. I resent being viewed as a native.

YZM: What is the biggest shared awareness you bring from this background to your novel?

EE: Rebecca and her father Isaac are refugees—fleeing England to find a safer, more congenial place to live. Throughout the novel, there is a growing consciousness of the changes to once tolerant Salerno that now begin to threaten Jewish life there. These underlying experiences of edginess fit in with patterns in Jewish life over the millennia, leading to a sense of wariness that is part of our, and certainly my, DNA. I fear we’ll be looking back at our current era as yet another time when it behooved people to pay attention.

There is, of course, Rebecca’s determination to live her best life as she sees it– to not give up her dreams of being independent and a healer. Despite the trauma and challenges they faced, my parents continued to pursue their vision of how to live. Marrying and having a baby almost immediately after being liberated is a clear testament to that. This thrust toward fully living was true for my mother until her last years, when dementia and depression brought her down. My father lived his idea of life quite literally to the last minute. I am trying, in my own way, to do the same. Writing is part of that process for me.