Surviving Mengele, Telling Their Story

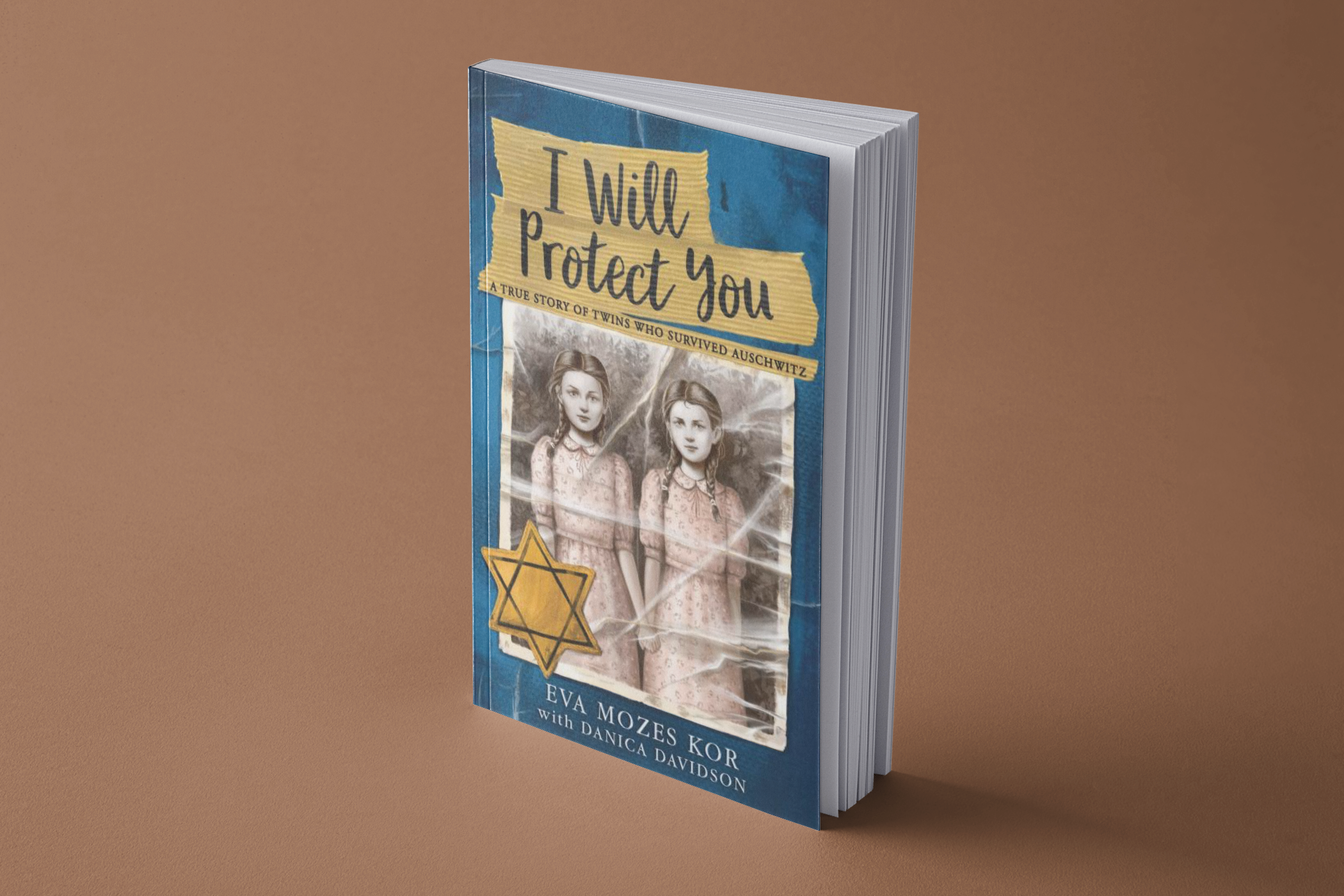

Though Eva Mozes Kor and her identical twin sister, Miriam, were part of the only Jewish family in their small village in the Transylvanian mountains, their childhood was mostly peaceful and happy. But first antisemitism reared its ugly head in their school —and then in 1944, ten-year-old Eva and her family were deported to Auschwitz. At its gates, Eva and Miriam were separated from their parents and other siblings, selected as subjects for Dr. Mengele’s infamous medical experiments. During the course of the war, Mengele would experiment on 3,000 twins. Only 160 would survive–including Eva and Miriam. Their story is the basis for I Will Protect You (Little, Brown $17.99) which was written by Eva Mozes Koa with Danica Davidson.

Davidson spoke with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough revealing how two young girls were able to survive the unimaginable cruelty of the Nazi regime, and how Eva was eventually able to the capacity to forgive. In an era of rising book censorship and hate crimes—even as survivors’ numbers dwindle–this book, Davidson and Eva’s collaboration, is all the more crucial.

YZM: How did you meet Eva and how did the book project come about?

DD: I met Eva when she gave a speech at Western Michigan University in fall 2018. I’d experienced antisemitism at a previous journalism job, and when I looked up what I’d been through, I realized I wasn’t alone. But a lot of the rising antisemitism isn’t discussed outside of Jewish circles, and I feel like a lot of non-Jewish people aren’t aware of it, or don’t recognize it when they see it. I felt a need to do something, and I figured the best thing I could do was start by educating myself. So I read a lot of Jewish books and saw Jewish speakers, and that included Eva.

I introduced myself after her speech, hoping I might be able to interview her, but when I mentioned that I wrote children’s books, she jumped out of her seat at me. She exclaimed she wanted to do a children’s book. She was elementary-school aged when she survived Auschwitz, and she was frustrated that Holocaust education in schools usually starts at 12, because she said that’s too late, since the prejudices are already set in.

So we discussed what could be done, and agreed to do a middle grade book (ages 8+). I interviewed Eva, and talked about angles. For example, I suggested the book have history interwoven in her story, so that it gives context to the situations. She really liked that. Most kids’ Holocaust books are either personal stories without the bigger context, or they’re textbooks without the personal touch. I wanted to blend these. I would email her chapters at a time as I wrote them. She would give me feedback on my chapters. The rough draft was completed in a fever dream in about three weeks.

YZM: What was it like for her to recount this story and for you to hear it? Did you do any additional research and if so, what was that process like?

DD: Eva was a Holocaust educator who retold her story a lot. The major parts of it you can find online. So I would press her about things I couldn’t find online. Things about her family, personal things.

I continued with my research on the Holocaust and Jewish subjects, and some of that went into the book. Before it was submitted to publishers, I Will Protect You was fact-checked by Holocaust scholar Michael Berenbaum, who has endorsed the book.

YZM: What were your concerns in presenting such difficult material to kids?

DD: The Holocaust is difficult to write about for any age. One of the key factors that makes this book work for kids is because Eva was a child when this happened, so it’s written from a child’s point-of-view. It would be harder to write a story for children if the survivor were an adult. But when you’re writing about Eva at this age, it’s Eva being bullied at school, Eva feeling jealous of her sisters, Eva being upset that the adults wouldn’t tell her what’s going on. Those are such universal things kids go through.

I think most Jewish kids know the details of the Holocaust when they’re young. I did. There’s nothing about the Holocaust in this book – besides the specific details of Eva’s life — that I didn’t know in elementary school. So it was being honest to childhood and honest to the facts of the Holocaust. Eva told me not to sugarcoat anything. The facts are here, but they’re told in a way that’s not graphic.

YZM: What do you hope the takeaway will be?

DD: I hope it reaches as wide an audience as possible, and I hope it removes some of the mystery of antisemitism, so people can recognize it when they see it and do something about it. It’s written for kids, but I wrote it in a way that older readers — including adults — can read it, too.

I also hope it gives people strength in hard times, to know what Eva survived. And I hope it is her lasting legacy.

YZM: Eva died before the book was published; does that add its importance and if so, how?

DD: It was awful when Eva died. We had accepted Little, Brown’s offer for the finished manuscript only fifteen days before. She was on an education trip to Auschwitz when she died, and no one was expecting it. Little, Brown and I took great care to keep the manuscript the way she approved, only doing small editorial tweaks to it.

We are losing survivors’ stories every day. I am heartbroken that Eva is not here to see the book’s publication, but relieved it was written in the nick of time, so that her story can go on for generations of children.

Eva will never be able to write another book, or give another speech. This is it. This is her legacy. That makes it all the more important, because her words can live longer than any of us.

YZM: Eva talks about forgiving Dr. Mengele—can you elaborate on what forgiveness means in this case?

DD: Eva spent decades hating Josef Mengele and the Nazis. Why wouldn’t she? But after decades, she found the hatred was chewing her up inside, and doing zero harm to the Nazis. She’d been part of a manhunt to find Mengele so he could be brought to trial, but he lived and died a free man.

Her idea of forgiveness is the dictionary definition — to stop hating someone. She felt that once she stopped hating someone, that person no longer had any power over her, and it was a source of strength for her.

Our book makes it clear that forgiveness does not mean pardoning, excusing, or forgetting. If someone is hurting you, there should be real-world consequences. For Eva, forgiveness was a healing technique for the harmed person, because it can give them their power back. Everyone copes with trauma differently. Eva hoped that her talks about healing and overcoming Auschwitz could be helpful to abused children around the world, to show them there are ways to heal, and that it’s not your fault that someone else has hurt you.