Maggie Anton’s New Novel of the Talmud

Content note: contains references to sexual assault.

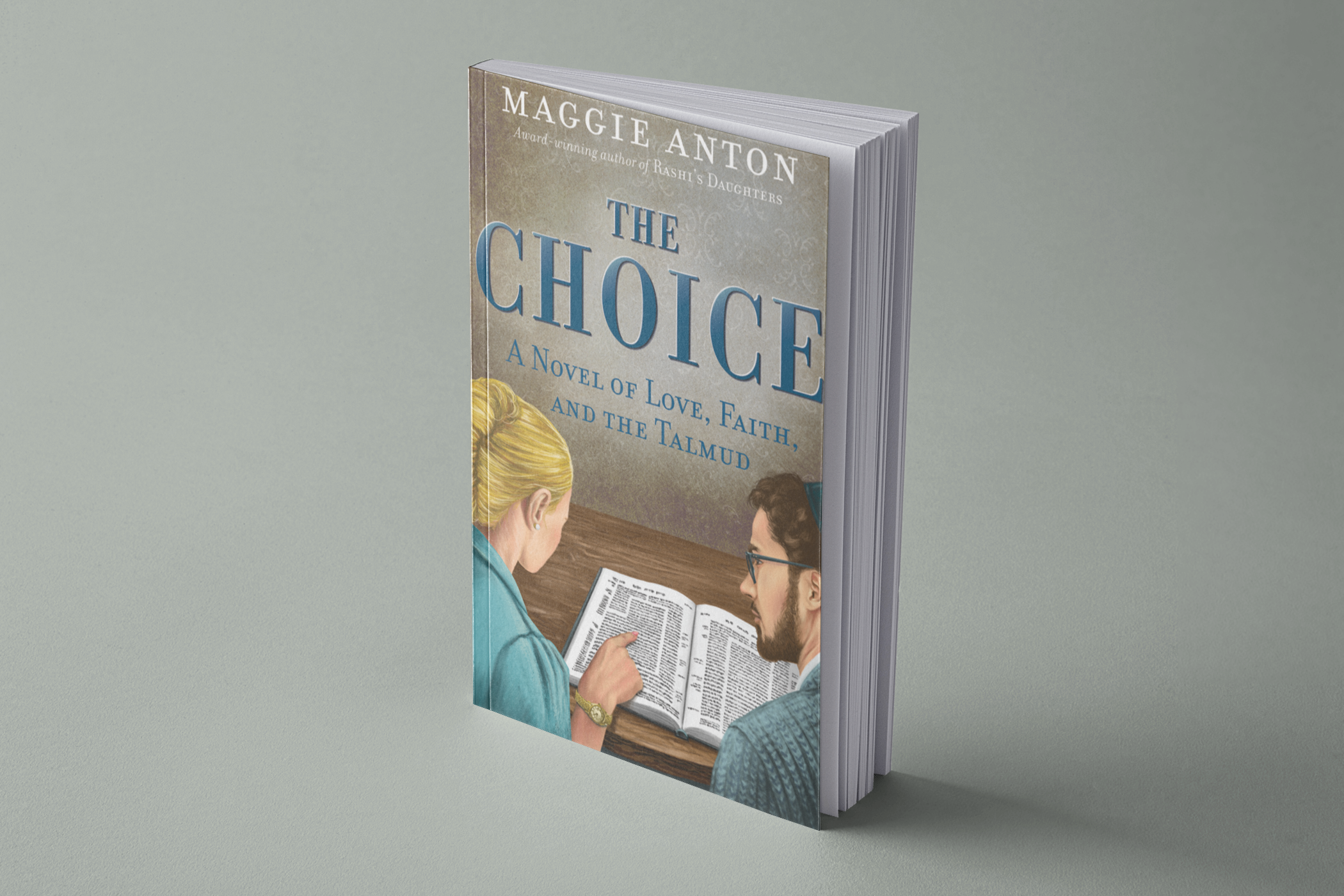

When journalist Hannah Eisen meets Rabbi Nathan Mandel, sparks begin to fly. Their mutual attraction grows when Hannah convinces Nathan to teach her Torah—something expressly forbidden by Jewish law. Set in 1955, in Brooklyn, NY, The Choice (Banot Press, $16.00) describes the many ways in which women have been given a subordinate role in Judaism.

Author Maggie Anton—who also wrote the acclaimed trilogy Rashi’s Daughters—talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about how her novel both exposes and dismantles these inequities in an effort to set the record straight.

YZM: The novel seems to have an important agenda in terms of creating parity between the genders within the Jewish tradition and practice; can you give us the backstory here?

MA: I was aware of gender inequality from when I was in grade school. Other students’ mothers were homemakers, but my mother was taking classes at Cal State, having been expelled from Michigan State in the 1940s when they discovered that she was married. My divorced bubbe (such a shanda) had always worked outside the home and my mother did too once she got her teaching credentials. But it hit me personally when, despite straight A’s and having a 1598 in math on my SATs, my high school counselor explained that I couldn’t attend Cal Tech because they didn’t admit women. So I went to UCLA, where I was often the only female in my upper division science and math classes. After my husband and I joined a temple in the early 1970s, it was clear that women were second-class Jews too.

YZM: Hannah persuades Rabbi Nathan Mandel to teach her Talmud, something that is strictly forbidden by Jewish law. Why does Hannah want to study this and what does it mean that Nathan is willing to break the rules for her?

MA: I modeled Hannah after myself. I was always someone who challenged authority and I wanted to see why this Jewish text called Talmud was forbidden to women. Hannah attended an Orthodox day school in the late 1930s, where she was an excellent student, but when she saw the boys go off to learn Talmud while the girls stayed behind to study Psalms and Prophets, I shared her anger and resentment. Nathan was her classmate and he too thought it was unfair when a boy received the most prestigious award at graduation even though Hannah deserved it. Later, when she asks him to teach her some Talmud, he feels guilty about the inequality and agrees, thinking it will only be for a little while. After all, he already broke the rules by using text criticism in his ordination exams. But once he sees what an excellent student she is, and how differently she questions Talmud compared to his yeshiva students, he can’t bring himself to stop teaching her.

YZM: You yourself are a Talmudic scholar—tell us about that journey.

Readers often ask how a girl raised in a secular socialist family in Los Angeles came to be a Talmud scholar. But this background doesn’t mean I lacked a Jewish education. I attended kindershul, run by Workman’s Circle. I also learned a great deal about Judaism from novels. For example: holidays, rituals, and the immigrant experience from All of a Kind Family; the Holocaust and founding of the State of Israel from Exodus; Talmud and the yeshiva world from The Chosen. From this last book, it was apparent that only males studied Talmud. In 1992 I heard about a women’s Talmud class being taught by feminist theologian Rachel Adler. She’d started this class because there was no place a woman could study Talmud outside of New York. Whether one called it excluded, prevented, or prohibited—women didn’t study Talmud.

I signed up for this class for two reasons. 1] Rachel Adler had such a great reputation that I wanted to study with her no matter what the subject was. 2] I wanted to see why this crucial Jewish text was forbidden for women. After all, as soon as something is banned, it immediately becomes more attractive. We met around Rachel’s dining table and every other woman there was a Jewish professional, or studying to become one, so I was way out of my depth. We used the Steinsaltz Hebrew version of Berachot, and I could barely keep my place, never mind reading aloud. Thankfully our discussions were in English, though it took hours of agonizing preparation each week merely to keep my head above water.

Our progress was sufficiently slow that as time passed, I was able to not only understand better, but also to participate. I learned that the first argument in a halakhic debate was a straw man, so obviously wrong that refuting it was easy. The second one was only slightly better, and if the subject were simple, the third would be accepted. A complicated debate might need many more arguments to resolve the matter. To my amazement, and delight, not all arguments were decided in one rabbi’s favor. Sometimes the debate ended with “teiku,” [let it stand], where each sage maintained his position. In other words, they were both right and Jews could legally follow either opinion. Thus Jewish Law was not so monolithic as I’d thought. Acceptance of diversity went further. Even when Heaven declared that halacha was with Hillel, Shammai’s students continued to follow their teacher and were not ostracized. Shammai even won occasionally. I was surprised to see that for issues involving women, Shammai frequently took the ‘feminist’ position, though these were the ones he usually lost.

Talmud became my passion. Every Wednesday night for five years I sat with other dedicated Jewish women as we worked our way through Tractate Berachot. Here I learned where the Judaism we practice today came from—synagogues, rabbis, observing holidays, our liturgy. The class ended when we completed that first tractate. Bereft, it took me some time to accept that my Talmud studies were over. Then we moved to a new synagogue, and on Rosh Hashana they introduced a woman rabbi who loved Talmud and wanted to teach it to us. My journey, apparently, had only just begun.

YZM: There are two sexual assault in this novel—can you talk about their consequences for each of the women who endured them?

MA: The first rape, of Hannah’s mother Deborah by a Cossack during a pogrom when she was fourteen, was part of Potok’s backstory for her. When Deborah’s religious father rejected her after the rape, Deborah in turn rejected Judaism and any belief in God. Though she eventually married an Orthodox man and lived an Orthodox lifestyle, she didn’t pray. I thought this history was too important to ignore, and after reading news about date rapes during Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court hearings, I decided to address that topic. Fraternity parties with spiked punch were such notorious dangers for female college students that it wouldn’t be surprising if my beautiful and sheltered Hannah suffered one in college. Nor was it surprising that she never told anyone about it until circumstances forced her to. It gave me a reason while she was still single at age 25, plus the first opportunity to write a serious conflict scene between Hannah and Nathan, as well as to question why single female non-virgins are considered tainted.

YZM: What do you hope your reader will take away from this story? Do you feel it will appeal only to Jewish women or Jewish men as well? What about its reception in the wider world?

MA: Of course I hope my readers will come away with some enjoyment from the romance and happy ending. And I hope the Talmud scenes will encourage some to study Talmud themselves. But I also hope they will take away the knowledge of how Torah and Talmud have been interpreted unfavorably toward women—especially in regard to marriage, worship, text study, and fulfilling mitzvot. I hope they will learn how that has changed over time, with Jewish Law being more lenient in Rashi’s 11th century French community, then becoming stricter in the 16th century when the Shulchan Aruch was printed, followed by Reform Judaism abandoning traditional halacha in the 18th century, after which Orthodoxy arose in response and required modern Jews to uphold 16th century halacha. I hope readers will understand how and why my protagonists ultimately move towards Conservative Judaism as a middle ground, as Potok did.

I assume The Choice will appeal to more Jewish women than men; that’s been the case with my earlier historical novels. But millions of people, Jews and gentiles, religious and secular, made Potok’s The Chosen a bestseller and I hope many of them will be curious to read my version of what happened later. Books and TV shows about Haredi Jews are popular world-wide today, so it would be nice if my book receives the same reception.