I Sing the Body Asexual

On subways, on TikTok, and in bookstores, I see evidence of a pro-sex, feminist cultural revolution: I see pins depicting vibrators and featuring the caption “Good Vibes Only”; I see sex workers given platforms on social media, bypassing censorship algorithms using tongue-in-cheek guises such as “spicy accountants”; I see “Cunt Coloring Books” proudly displaying vulvas on bookshelves. I see these celebrations of sexuality and sex-positive feminism around me, and I find myself celebrating with them.

No longer are we forced to hide the natural beauty and pleasure of sexuality and the human body — what was once shameful is now lauded in the face of patriarchy and purity culture, and this sentiment only continues to grow and spread. Even in the Orthodox community I live in, I find my friends speaking more openly and honestly about sexuality. As a sex-positive feminist, I revel in this.

However, as a sex-neutral asexual Orthodox Jewish woman, these experiences leave me wondering: where do I fit in?

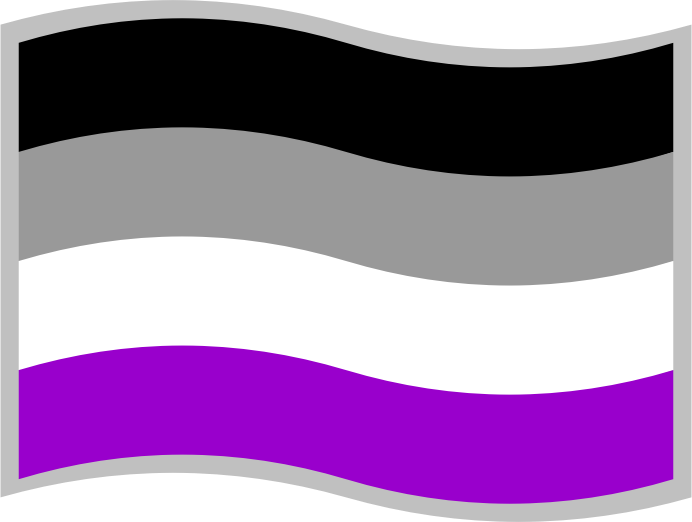

I’ve never experienced sexual pleasure, whether by myself or with another person. This isn’t repression, or confusion, or voluntary celibacy for ideological reasons. Asexuality is its own distinct orientation within the LGBTQIA+ community. The Asexual Visibility and Education Network(AVEN) defines asexual people as people who “[do] not experience sexual attraction – they are not drawn to people sexually and do not desire to act upon attraction to others in a sexual way.” This manifests in many ways along the spectrum of sexuality: for example, some are sex-repulsed, some are sex-favorable, and some only experience sexual attraction under specific circumstances. Some asexuals masturbate, some have sex with partners, some do both, and some do neither. I am a sex-neutral asexual. Most of the time, I am comfortable with my neutral personal relationship to sex. I acknowledge and advocate for the importance of sexual health and pleasure, but don’t actively seek it out for myself.

However, in conversations about feminism, I sometimes feel like an impostor. Am I truly a woman who fights for liberation if I am not a sexually liberated woman myself?

I’ve tried plenty of times. I’ve scrolled through pages of vibrators on online stores, mustered up courage to enter sex shops in person — I even, on more than one occasion, put it on my Google Calendar so I would see it on my to-do list. So many times I have intended to venture into masturbation, just to try to experience some of the liberation I advocate for, but it has never felt natural the way people say it does. It feels like eating with no appetite or sleeping when I am not tired — it is just not something I want at that moment.

And I do not know if it will ever be. While I am normally satisfied with that, I can’t help but feel some shame when I see “Good Vibes Only” pins and raw, honest social media posts about the joy of orgasms. Am I a hypocrite, encouraging open sexuality that I do not seek out for myself? Am I part of the problem, a woman who does not personally engage in the empowerment of sexual pleasure? I worry that I am a walking contradiction. I wonder if the sex-positive feminist movement includes me in its mission.

As if my personal identity hasn’t provided enough confusion, I’m also a Modern Orthodox woman. My community is seldom, if ever, considered a community of sexual liberation. Growing up attending a Jewish Day School, I did not learn in-depth about sexual or reproductive health in a classroom setting — not because my peers were fully celibate, but because the greater Modern Orthodox community operates with the notion of complete youth celibacy that both the youth and the community leaders alike know to be a fallacy.

While our school taught us about modesty and pretended we all adhered to their standards, everyone knew who was hooking up in their cars after school. This approach led to misinformation about sexual health and an air of shame with regard to sexual activity. Many of my peers continued to engage in activities of sexual pleasure without protection, simply out of not understanding the necessity. They experienced an immense weight of shame and guilt about their experiences due to purity pressures from both the Orthodox community and the wider secular society around us. Both gave us messages about virginity, purity, and “damaged goods.”

Meanwhile, others who took these messages and adhered to them strictly as youth experienced anxieties (and even trauma, in some cases) as adults when, approaching their weddings, they were suddenly expected not only to undress in front of another person, but to suddenly engage in these previously forbidden and shameful acts with them.

As an adult, I have had conversations with peers of diverse Jewish backgrounds about sexuality through a Jewish lens. My peers have described feelings of loss of purity due to sexual experiences, both overt and passive-aggressive slut-shaming from community members, confusing being in relationships with giving consent, and other difficulties. Many of these friends, sex-positive feminists themselves, have spoken of about the power of self-pleasure with regard to forming a positive relationship with sexuality. Through this medium, they have learned more about what they want and gained a perspective on sexual pleasure as being healthy and natural.

If female masturbation has not been encouraged in the secular patriarchal society, female masturbation is so taboo in the Orthodox community that it is not even openly condemned. While no masturbation is condoned in the community, male masturbation is, at the very least, acknowledged. Bookstores throughout Meah Shearim in Jerusalem boast titles of books such as “The Battle of Our Generation,” that aid men in resisting their “evil inclinations,” but what about women?

When I once asked a teacher about this in high school, the teacher sharply responded, “Women shouldn’t want that type of thing.” Thus, my Orthodox friends’ ventures into self-exploration are that much more revolutionary: not just to embrace pleasure, but to even open up the conversation!

As much as I commend my friends for embarking on such a journey for themselves, I am not able to relate to this experience. I am not opposed to sex with my (G-d willing) future spouse for their sake and for (if applicable) procreation, but I do not personally crave sex or experience the “horniness” my friends joke about. I acknowledge the human body as beautiful, but I relate to it differently.

And yet, my life as a feminist, as a modern Othodox Jew, and as a sex-neutral asexual has actually allowed me to think about these questions with more depth than others. Having pondered for a long time, I have begun to learn a new answer to many old questions. Sex-positive feminism and sexual liberation are not celebrations of sexual activity, but celebrations of sexual agency.

So many generations of women have been shamed for sexual interest or activity, but just as many generations of women have been targeted for saying “no”, for being “frigid”, for not putting out. Just as we celebrate women who say “yes” to what they want, we celebrate women who say “no” to what they do not want. Sex positivity should be about what feels right — whether that means going to bed with a vibrator, a hookup, or a really good piece of garlic bread (it’s an asexual thing. If you know, you know). If there is one thing I have learned in this journey of identity and philosophy, it is that there is room for empowerment both in being sexual and in being nonsexual.

In conclusion, I am not a walking contradiction. I am a sex-positive feminist and a sex-neutral asexual and a Modern Orthodox woman all at once. I am a sexually liberated woman. I know myself and my needs better than anyone, and you know yourself and your needs better than anyone. And whatever those needs are, I support you. And I look to you to support me.

Daphna Silver (not her real name) is an ambitious, firmly feminist twenty-something pursuing a graduate degree in psychology. When she is not working or studying, she loves to write and explore the abundance of adventures NYC provides.