Muslims & Jews— Building Our Emotional Safety Net

When Rabbi Charlie Cytron Walker and several of his community members were taken hostage in their synagogue in Colleyville, Texas, both of us were out of easy communication range. Andrea’s Shabbat observance meant her phone was off until havdalah (the end of Shabbat) and Aziza’s family had taken a weekend away from their home where the cell reception was intermittent. As, respectively, associate and executive director of NewGround: a Muslim-Jewish Partnership for Change, our people were hurting—and neither of us was in a position to connect with our community in the way they needed and wanted us to.

And yet, the resilient relationships we have built over the years were there to hold us all. Not perfectly—in the days after, it became clear that there were still gaps in communication to be bridged and silences to be spoken into. As we navigated the following days and weeks, we returned again to these questions:

What helps us strengthen our honesty, authenticity and accountability with one another to ensure that we can stand together when it matters most? What can we learn from this moment?

We hope that our account might shed light on what it means to show up for another, and some of the paths for getting there.

Aziza’s Story

After recovering from Covid the subsequent quarantine, coupled with the general exhaustion of working and parenting, my family and I decided to spend a long weekend in the desert. As we were driving, I received a text message. It was from a friend, the Jewish co-chair of NewGround’s board. She told me and the organization’s Muslim co-chair to keep an eye out for “developments around Colleyville.”

I had no idea what she was talking about.

When I searched on Google, my phone wouldn’t load the results. A little later, I received a speaking request to pray at Temple Israel of Hollywood during havdalah in a special online service that evening for the safe release of the hostages. Realizing my phone had reception in the spot we were driving through, I searched Google again. I learned that hostages were being held in their sacred house of worship. My heart sank to my feet. “Ya Allah!” (Dear Lord) I said out loud. Noticing the exasperation in my voice, my husband asked me what was going on. When I told him, he said, “Please God, don’t let the hostage taker be Muslim.” A heavy silence set in as we continued the windy drive down to our desitnation. Given my unreliable internet connection, the Muslim board co-chair, Nurya Shabir would speak instead of me at the online prayer gathering. She knew she had to be there, sharing scripture from both the Talmud and Quran that to take a life is as if killing the entire world and to save a life is as if saving all of humanity (Talmud, Sanhedrin 37a; Quran 5:32).

Meanwhile, I felt stuck in the expansive outdoors. I couldn’t stop thinking about the families waiting for the hostages. Loved ones whose hearts ached for the safety of a parent, a spouse, a child. In the days and weeks that followed I witnessed friends, who were wrestling with what it means to be Jewish and join together in communal prayers. Being attacked for being Jews. Listening felt inadequate, words were never the right ones, and reaching out was not fast enough. Too many people were feeling alone and isolated in their anguish. As the outreach continued via text, phone calls, email, social media feeds and Zoom conversations. I sensed that people felt betrayed when they were not contacted personally, and sooner. Every conversation was different and yet entirely the same.

That’s when I realized that if I “shushed” him, I would be silencing my son’s joy and his pride – even his sense of God in the world. How could I? I wouldn’t. I couldn’t.

Two weeks after the incident, we convened a two-hour Zoom session of the professional alumni of our program, and we each shared our perspectives. Bearing witness to one another. Calling out what felt inadequate in ourselves and things around us. I shared a story from a recent hike with another family and my own. When we reached a waterfall, my sons threw back a tennis ball that some visibly observant Jewish kids were using to play fetch with their dog. We were all enjoying nature together. My Muslim kids and their Muslim friends, and the Jewish kids and adults. My family and I hiked away from the falls, leaving the Jewish family to enjoy them. After some time, my eldest and his best friend were straggling behind, enjoying the water and valley we were hiking through, when they both called out loudly, “Allahu Akbar!”

Thinking of the Jewish kids (now far behind us) I turned to “shush” the boys. They were smiling with joy and pride. My son said, “wouldn’t it be amazing to fill this whole valley with ‘Allahu Akbar’? Isn’t it beautiful!?” That’s when I realized that if I “shushed” him, I would be silencing my son’s joy and his pride – even his sense of God in the world. How could I? I wouldn’t. I couldn’t. But I must find a way that all our kids, Jewish, Muslim, and others have a space to both share their joy and their pain. To be fully seen and fully heard. And to share nature side by side without fear of one another.

After sharing this reflection, a Jewish alumna, and also a dear friend, said “how beautiful that we should all be praising God out in nature!” Another chimed in— she appreciated the sentiment that we can all have a space to be side by side. I had entered that conversation feeling so inadequate, and by the time I left a weight had lifted.

I wanted so badly to be an ally. But I also felt like my children’s identities were on the line.

Relationships help us find a way to see one another while holding our own faults. They create the will to provide the brave container for our vulnerability to be shared. Sometimes I still feel a loss for words. But I know that when I show up—even when I have no idea what to say— I start to understand more deeply. I know the simple and beautiful act of chanting “God is greater” in Arabic can invoke a fear response in non-Muslims who have been robbed of knowing these words because they have only heard them in the context of their blasphemous misuse by some Muslims and their amplification in popular media to sell fear. In that valley, I was sensitive to what this Jewish family might be feeling in the days following the hostage situation, and it made me ache inside. Had I not seen the joy on my child’s face and waited for a beat before acting on my instinct to silence him, I would have missed the very sentiment his words came from. He was admiring the majestic natural tapestry woven all around him.

I wanted so badly to be an ally. But I also felt like my children’s identities were on the line. I am working hard to raise two boys to love justice and walk in humility with Islam as the source of these teachings. Every day this feels like an uphill climb – countering misogyny, facing racism and xenophobia – and in that moment it felt like the incline got exponentially steeper. With the very source of inspiration to address all of this snatched out from under us. I recognized my role as a parent was to hold space for my son’s unbridled joy, unencumbered by the social context we were in. I needed to take that breath and wait that beat before responding—we all do in moments like these. But it wasn’t sitting right with me until my friend reflected back to me the power and beauty of my choice. Her compassion helped me release myself from the feeling of shame I had been holding onto. It takes this level of vulnerability and honesty in both directions for us to fully stand as allies for one another.

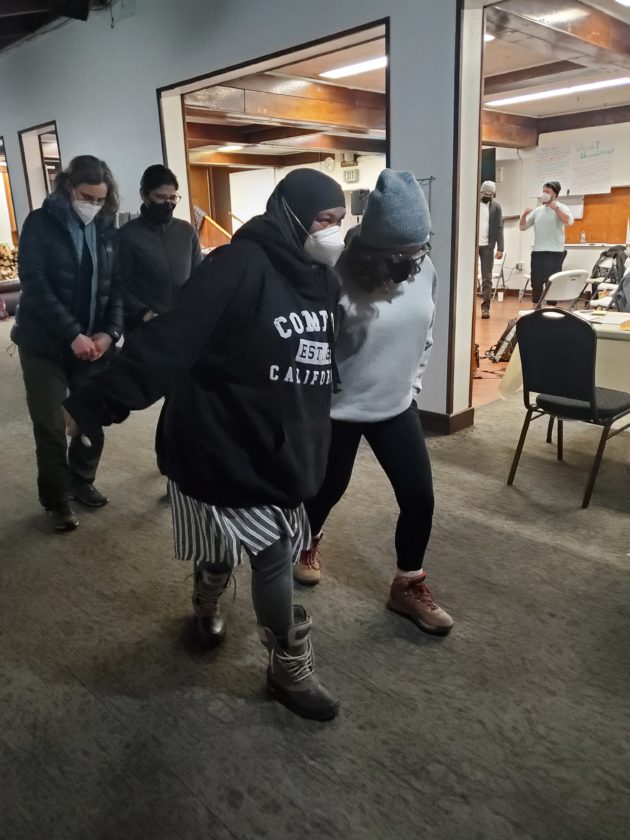

As it happened, in their next session, our current NewGround Fellows, 16 people spending the year building relationships and holding critical conversations, would be gathering to begin untangling antisemitism and Islamophobia. This isn’t new. We dive deeply into it every year, because both keep getting worse and worse. And we know, from experience, that the only way through it is together. Through the messy entanglement of holding how our words can affect one another’s loved ones. Through the impact of hearing from those we trust what we are at times too defensive to see.

Andrea’s Story

I opened my phone after Shabbat to a string of text messages from my Muslim friends and colleagues who were already in motion, making plans about who would speak to which synagogues that night. While juggling several Fellowship WhatsApp groups, and scrolling through the news to try to catch up on what was happening, my husband and I listened to a public recitation of Psalms being held on Twitter. I had only a few minutes after Shabbat ended to help Nurya (New Ground’s Muslim board co-chair) prepare her remarks before the Havdalah service began. Our Jewish co-chair, Rabbi Sarah Bassin, a friend and colleague of Rabbi Charlie, sent us some statements about solidarity, from his previous writing, which we incorporated. Later that evening, I received a text from Nurya: “Just finished . . . I got v emotional in the middle.”

As I worked with another Muslim friend who had been invited to offer a prayer at a different synagogue, I found a Twitter thread of anguish and support from one of Rabbi Charlie’s Muslim colleagues, which my friend quoted in her prayer to convey the sense of the interconnectedness of our all our communities. Even as I was scrambling post-Shabbat to get my bearings, it was immediately apparent that Rabbi Charlie was a part of interfaith networks like ours that take tremendous dedication to cultivate and sustain . . . and when we need them most, they are there to hold us. These relationships do not appear out of thin air, but are forged over time, and are often hard-won.

By then, it had become clear that the person holding those in the synagogue was Muslim. While I listened to the Psalms with prayers in my heart for the safe release of the hostages, my mind also turned to the implications of this for my Muslim friends. My support of their strong voices and hearts in support of our Jewish communities felt even more critical. Once I had connected a few of these threads into whatever spiritual and emotional safety nets our communities were building together that night, I was able to turn to my own prayer community where we were gathering for Torah study. Our Shtibl Minyan is small, and one of our members, Rabbi Mike Comins, had recently returned from several years as a rabbi in Dallas, where he was part of a weekly coffee meetup with Rabbi Charlie and several other rabbis. He told us how much he needed to be with our community in prayer and study as he waited for any news of his friend. After some moments of silent prayer, we were studying the parting of the Red Sea from that week’s Torah portion when the news came in on his phone––the hostages were out safely! And, like the sea parting, a moment of the deepest fear and uncertainty turned into a moment of great relief and gratitude, flowing out in tears that could not be contained.

And it isn’t until I sit here writing this piece, remembering the feeling of scrambling in fear as I emerged from Shabbat, and I look up to read Aziza’s description of her Jewish friends “wrestling with what it means to be Jewish and join together in communal prayers. Being attacked for being Jews” that I realize how much fear I was blocking that night, and still am. AND I also realize that when we are truly seen, it can allow us to feel held, and to feel what it is we need to feel . . . and then, to heal.

The next day, when I reached out to Mike to see how he was doing, he told me that before joining our Torah study, he had been in the Temple Israel of Hollywood Havdalah service. “Nurya’s emotion was so genuine and SO comforting to hear. Please let her know how much her words helped me.” Both Mike and Sarah confirmed that the interfaith mobilization we recognized from afar came from a strong foundation that Rabbi Charlie had been a part of building. Even in the shakiness of the moment, it felt comforting to know that these lines of connection were holding all of us together.

It became clear to us over the next week, however, that not everyone was feeling this interconnectedness in our community. Our Fellows seemed uncharacteristically quiet. I had many long conversations that week with our Jewish community members and Muslim community members. Many of the Jews were feeling isolated. Many of the Muslims, living with the scars of being raised in a post 9/11 world, were holding their own fear and confusion and weren’t sure what to say.

When we offered a session for our alumni to create a space for raw conversations as we had in May and June during the violence in Gaza (and will soon, again, to talk about house demolitions in Sheikh Jarrah) the Zoom filled up with Muslims first, who came to listen and offer comfort. As more Jews popped in, they were able to fully air their sense of isolation in this moment––breaking through it even in the expression itself. Just as I felt held by Aziza as I read her words above, our Jewish Fellows felt held and heard. And there was room for the Muslims to really speak as well. They know that feeling of fear and isolation all too well. Some articulated feeling it that week, anticipating the fallout, because when a Muslim person is responsible for violence somewhere else, they or their family members might be “implicated” by the mere fact of their identity or language. They didn’t want their Jewish counterparts to be carrying that sense of isolation and vulnerability either. At least not the kind of vulnerability that leads to deeper fear. It is in this space where our vulnerability is welcomed and safely held that we grow stronger, together.

Aziza & Andrea:

The gratitude we felt to have this space to see and be with one another as we are, was only a sliver of the gratitude Rabbi Charlie articulated in the healing service on the Monday evening after he was released. “How amazing is it for us to know that we have the support of the broader community . . . that our broader world desperately wants to support us on this journey (of healing)?” he said.

When communication is blocked for one reason or another, we need to keep coming back to the table. And back, and back again.

As we experienced our communities reaching out to one another in a moment when it seemed all we could do was pray, it was deeply heartening to know that in Colleyville, the community had shown up for the Congregation Beth Israel community and Rabbi Charlie so meaningfully. The ways we reach out to one another during these times have sustaining power. From the edge of our seats in Los Angeles, we could feel the power of the relationships Rabbi Charlie had taken the time to build in his community. We could see the outpouring of care and love from his colleagues across the country, and his interfaith colleagues across his city. Especially his Muslim colleagues.

We know from our own work building resilient relationships between Muslims and Jews that these lines of care and communication don’t happen by accident. When communication is blocked for one reason or another, we need to keep coming back to the table. And back, and back again. But the investment is worth it, because these are the very resilient relationships that will sustain us all for the road ahead.