Eileen Pollack on Sexism—from Physics Departments to Dating

Trained in science, Eileen Pollack has gone on to be a novelist, short story writer, essayist, professor and (former) director of the Helen Zell MFA Program in Creative Writing at the University of Michigan.

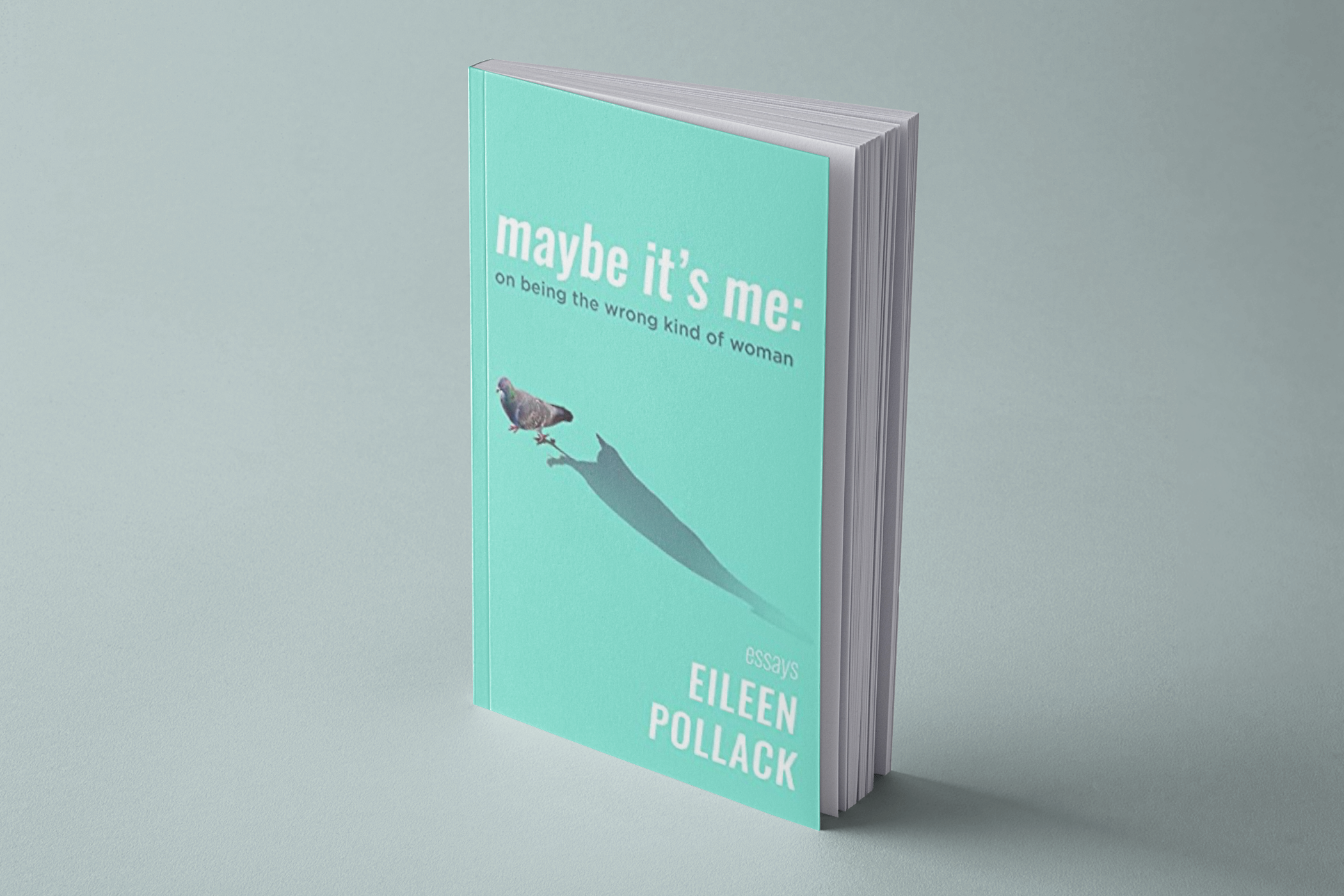

Her latest essay collection, Maybe It’s Me: On Being the Wrong Kind of Woman (Delphinium, $27), pulls together her smart and often fiercely acerbic observations. She talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about why, despite all the strides women have made, everything from science to dating feels like a boys’ club.

YZM: You were one of the first two women to graduate from Yale with a B.S. in physics; what was that like? Was there a lot of bias against women? Did you feel discouraged from pursuing a more advanced degree in science? Any regrets about not having done that?

EP: Funny you should ask! My memoir The Only Woman in the Room was written to answer each and every one of those questions. In 2005, Larry Summers, who was then president of Harvard, asked his faculty why there weren’t more women in the hard sciences. His lunchtime musings–maybe women just didn’t want to work as hard as men or weren’t as gifted in science and math at the very highest end of the spectrum–caused female faculty members to leave the room. I’ve known Larry since high school debate, so I sat down to write him an email explaining why I hadn’t gone on in physics, even though I’d wanted nothing more than to study space and time and relativity. At three in the morning, I had a very, very long email … but I realized I didn’t know the answer to my own question. So I wrote what I call an “investigative memoir” to figure out why I’d left physics. The long answers to all your questions can be found in The Only Woman in the Room; the shorter version ran in The New York Times Magazine. The very short answer is: Yes, there was bias, but it was subtle enough that I didn’t understand what I was suffering. My professors thought they shouldn’t encourage ANYONE to go on in physics or math, but in fact, they were not-so-subtly encouraging the boys to go on, and not-so-subtly discouraging me (even though I graduated at the very top of my class). And society at large was actively encouraging boys to go on in science and actively discouraging girls. So yes, I have many regrets about not becoming a theoretical physicist.

YZM: What about bias against Jewish women?

EP: Yale was full of Jews, even then, but they were so sophisticated and assimilated I honestly didn’t even know they were Jewish. I was the only Jew who had grown up in the Borscht Belt, I can swear to that. I quickly learned not to use any Yiddish. I tempered my accent. I straightened my hair. And by the end of four years, I was attending Unitarian services. (To be fair, I did date a Jewish guy who led me to the campus rabbi’s study group, and I had a wonderful professor named Maurice Natanson, who understood who I was and where I came from and turned me on to Martin Buber. My writing professor, John Hersey, who was a missionary’s son, turned me on to Grace Paley and Leonard Michaels and Philip Roth. Hersey was such a mensch … Even though he was a WASP, he wrote the novel The Wall, which was one of the very first works of fiction about the Holocaust.)

YZM: Growing up, you lived in “heart of the Jewish Catskills.” What was it like to be a year-rounder in a summer community? Was it very Jewish in the off-season months?

EP: Much of my fiction has been devoted to describing the craziness of growing up in the Catskills (see, for example, my two novels The Bible of Dirty Jokes and Paradise, New York, and my two story collections,The Rabbi in the Attic and In the Mouth). Jews in America are currently enjoying a wave of nostalgia for the Borscht Belt. The hotels certainly did provide a sense of community, a breeding ground for comedians, and a way for immigrant Jews and their offspring to learn to enjoy sports, leisure, the outdoors, and each other’s company at a time when most hotels did not accept Jews. But growing up in Liberty was like growing up in Las Vegas. There was a lot of crime (organized and not so organized), casual sex, abuse of workers, racism, sexism, etc. I try to portray the Catskills as they really were, which some people find interferes with their desire for pure nostalgia.

YZM: Over how many years were these essays written? Have your feelings on any of the topics you covered changed significantly and if so, how?

EP: The essays were written over the past 20 or 25 years. I didn’t include any essays that no longer expressed my feelings or beliefs. What has changed is that there finally is an audience for personal essays. People used to hear the word “essay” and think only of those awful five-paragraph monstrosities they were forced to write in junior high and high school. Essayists like David Sedaris, Roxane Gay, Rebecca Solnit, Jia Tolentino, and the greatly mourned Joan Didion helped to change that perception.

YZM: Let’s talk about the title essay, Maybe It’s Me: On Being the Wrong Kind of Woman. What exactly does that mean? Do you feel like the combination of romance and parity can really exist between a woman and a man?

EP: The essay was inspired by five horrifying years spent dating as a sixty-year-old woman in Manhattan, but in a larger sense, I am really trying to take on the incredibly narrow definition of “the right kind of woman” most men want to date, a definition that most women find virtually impossible to fulfill. Insult by insult, rejection by rejection, most women start to feel “wrong.” (I recently dated a man who thought I was so different from other women that he kept calling me an “alien from another planet,” and that’s someone who did want to date me!) I wanted to look more closely at that whittling away of a woman’s confidence, her increasing uneasiness with who she is, her belief that even though she has the genes to be female, she isn’t the right kind of woman. (In a sense, the experiences I describe in the title essay apply mostly to straight women, but I think queer readers can identify with the experience of not fitting the screwy definitions of gender that society imposes on all of us. Many of my friends and students and colleagues belong to the LGBTQ+ community. I try to recognize their experiences in my work, but they are the experts, so I turn to their writing for a clearer sense of how all these definitions of “right” and “wrong” affect their lives.)

I do feel that a woman can be loved for her mind and personality as well as for her body; the man I’m dating now seems to be doing a great job of that. But it’s not easy to find such a relationship. As I say in the essay, women my age are dating men who grew up in a completely different culture as regards the status of women. Many of those men have made barely any effort to change their views or behaviors. Some think they have changed a lot, but they actually have changed very little.