A Novel Takes on the Thorny World of Surrogacy

Struggling to make ends meet, a young woman named Maggie decides to be a surrogate for a gay couple who want her to carry their child. When twins are born, she hands them to their new parents and never looks back. But ten years after the fact, she makes a horrifying discovery about one of these children.

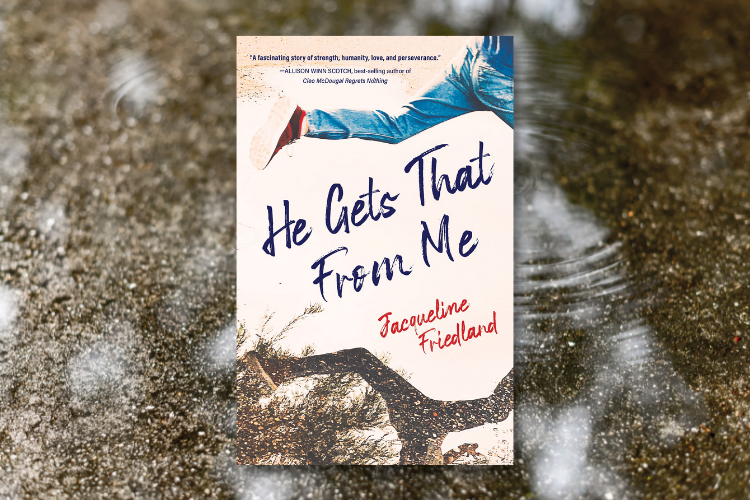

This is the premise for Jackie Friedland’s probing and up-to-the-minute novel, He Gets That From Me (Spark Press, $16.95). Friedland chats with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the nuances and potential landmines that exist when dealing with such a radically new way to bring children into the world.

YZM: Your book really asks some deep questions—what constitutes a family? Where do we belong?

JF: The book tells the story of a young woman who serves as a surrogate mother only to discover, ten years after the fact, that she accidentally gave away her own biological child. It’s obviously very difficult for Maggie, the surrogate, to discover that she has a child she never knew about and whom she unknowingly abandoned (or sold, depending on how you look at it). It’s equally difficult for the parents who have been raising this child, Kai, since he was a baby, to learn that someone else might have a claim on him. As the parties navigate the complexities of this situation, they all begin to question where this child most belongs, what makes a parent, how to know what your child really needs, and which types of bonds are most important in our lives.

YZM: You seem to know a lot about the science underlying surrogacy.

JF: There was a lot of reading of medical and legal information that I had to do before writing. Even so, I find that the best way to do research for a novel is to talk to real people. I spoke with multiple parents who have had babies through surrogacy, or used other forms of third-party-assisted reproduction, as well as some who have adopted children, and also others who considered, but rejected, the idea of using medical interventions to help build their families. I interviewed fertility specialists, obstetricians, and pediatricians. I also connected with some surrogacy agencies who introduced me to women who have served as gestational carriers. These women, for the most part, were incredibly generous with their time, and I felt so grateful to learn about their experiences carrying babies for other families. I also spoke with surrogacy attorneys from New York, Arizona, and California, the three states where my parties reside at different times throughout the book. I was very lucky to connect with so many people who were so willing to share their stories to help make this book as realistic and as relevant as possible.

YZM: If surrogacy is going to become more commonplace in the future, what safeguards can make sure that children born through this method aren’t exposed to the kind of traumas you hint at here?

JF: I do, indeed, feel that surrogacy is going to become more commonplace. I am a New Yorker, and during the time I was writing the book, New York legalized surrogacy. We were behind the times on that, if you ask me, as surrogacy has been legal in many states for years and years. But I do think that an increasing number of states will follow suit. Regarding the trauma referenced in my book, superfetation (getting pregnant with a second child when one is already pregnant from a prior conception) is incredibly rare. When a person undergoes a medical procedure, there are always risks of crazy things happening, and certainly, in a fertility situation, surprises can sometimes be overwhelming. That said, the number of positive outcomes from fertility interventions so massively eclipses the number of “mistakes” that things like I’ve described in my book really should not factor into the decision of someone considering a surrogacy arrangement. And for those who are simply so worried that they can’t ignore the possibility, there are ways to avoid it, such as insisting that the carrier take progesterone, a hormone that prevents the release of subsequent eggs during pregnancy, or adding a clause to the surrogacy contract that prohibits intercourse for some very long duration of the pregnancy.

YZM: One of Maggie’s regrets is her feeling that she feels she’s failed to connect her son to his Jewish heritage; do you feel that complicates the issue for her?

JF: There is so much about discovering the existence of a ten-year-old son that Maggie could not have anticipated. With each passing hour, she realizes another facet of the child’s life that she has missed out on, or she thinks of another person who has lost out by being kept away from the child, whether grandparents or siblings or herself. When she thinks about her Jewish heritage and the importance of passing on her traditions to her offspring, she feels another loss knowing that her biological son is not being raised within her faith. It’s definitely not something she ever thought about before deciding to be gestational carrier for another couple.

YZM: Without giving too much away, there are a couple of surprises at the end, including one about Maggie and her husband Nick; why did you shy away from a conventional happy ending?

JF: It was very important to me to portray Maggie and Nick’s marriage in a realistic fashion. I didn’t want to show a Hollywood happy ending where everyone walks off into the sunset. Marriages take all forms, and Maggie and Nick’s is one that is “good enough.” We have a man and a woman who love each other, but who are always out of sync. And try as they may to connect better or support each other better, they just keep getting it wrong. Even so, they are not interested in being apart from each other. In some ways, I think this is a happy ending because it shows that people don’t have to be satisfied with every aspect of another person in order to be committed to them. I hope that readers can see the of optimism in that.