“Ismail’s Dilemma”: Hidden Jewish Histories of the Balkans

Albanian history is rarely found inside of a book. It lives, like much of Jewish history, in the mouths of our parents and grandparents—especially women. When they choose to share stories with us, it feels like listening to a precious broadcast from another time. This is what I felt watching Dilema e Ismailit (Ismail’s Dilemma) directed by Dhimiter Ismailaj-Valona. In a story about gentile Albanians protecting Jewish ones, I saw what my Muslim great grandparents, living in Nazi-occupied North Macedonia in the 1940s, experienced.

The film focuses on the mounting stress facing a man named Ismail, his family, and the two Jewish men they are sheltering during the Nazi occupation of the Balkans—specifically, the encroaching threat of officers investigating hidden Jews in Ismail’s village.

“It sounds like a fairytale,” Ismail says of besa, the pan-Albanian concept of honor and justice. A viewer can’t disagree with him. The film doesn’t shy away from the horrifying and under-discussed realities of Nazi occupation, including the threat of random violence.

I held my breath watching as the portrayal of Nazi-occupied life painfully wormed its way into my chest. My own great-grandfather was shot and killed after visiting his sister and father in a nearby village, against the advice of his family and neighbors. They knew that the area was crawling with Nazis, but thought that his sister would be safe without him, among female relatives and my great-grandfather’s elderly father. His wife, my great grandmother, was unable to raise their son—my grandfather—alone. My grandfather grew up surrounded by the aftermath of Nazi occupation; by Yugoslavia’s treatment of its non-Slavic and non-Christian ethnic minorities; and by his family’s tumultuous relationships. This trauma, and subsequent alienation and insecurity, shaped the lives of my ancestors, my father and his generation—and defines mine. I felt seen by Ismail’s Dilemma.

The film refuses to engage in valorization. My own generation, millennials and Gen Zers, are prone to sorting people into ‘hero’ or ‘villain’ categories. Similarly, documentaries and films often retroactively embellish and flatten people, buffing away their complexities and nuance. Ismailaj-Valona carefully portrays Ismail as a person trying to do the right thing under life-threatening circumstances; the film’s protagonist has moments of total burnout from his constant vigilance and no longer wants to shelter his Jewish guests. The protagonist is not hateful towards Jewish people as a group, but is exhausted by the daily toll of doing the right thing at the risk of serious punishment.

Unusually for this genre, the plight of women during and after wartime is neither minimized or judged. In fact, a feminine oral history is exactly what gives Ismailaj-Valona’s film its realistic touch. During our interview, he shared, “It’s actually from my mom’s story. So she told me so-and-so, about the guy. ‘We had this guy who stuttered, and he was the spy of the village’ and that’s how he spied on her father and other people who were with the resistance.” The director’s inclusion of his mother’s voice and memory is a testament to the theme that Ismail’s Dilemma is concerned with the most: making a lasting, positive impact on the world.

My interfaith upbringing means that I faced many moments of racism, Islamophobia and antisemitism, in large part at the hands of my own family.

Dilema E Ismailit made me feel good that I have the courage to speak up when I do: when I want the antisemitism or Islamophobia I’ve experienced acknowledged. Its narrative values the actions and agency of humans over the intervention of heaven. In a moment of crisis as Nazis surround his house, Ismail says to his ally, the Catholic Father Leka, “Jesus and Allah are off today, father. If they were working, they would send us chickens and not jackals.”

Every scene of the film affirms that history is far away, yet we live its consequences at every moment; and in every moment, we are making history, too. When Ismail is about to give up, his wife, Shkurta, is the one who demands that he not betray their Jewish guests or act in any way that would dishonor their family. She does this even knowing what consequences she may face if she and Ismail are discovered to be hiding Jews.

My interfaith upbringing meant that I faced many moments of racism, Islamophobia and antisemitism, in large part at the hands of my own family. Often, when I try to speak about it, I am silenced by cultural narratives that want our ancestors and families to be purely good or purely bad, when they’re neither—only human. My communities were not accountable to themselves or their diversity. Instead, many of their worst fears were taken out on me.

As I get older, I come across new support systems for Muslims and Jews in interfaith relationships, and the children of interfaith Jewish relationships. On the one hand, I often feel sad and resentful that they didn’t exist when I needed them most. Moreover, like Ismail, I’m resentful of a set of rules that made my communities feel a need to act the way they did, instituted long before any of them were born. On the other hand, I’m happy the next generation has them. Part of me wonders whether stories like Ismail’s Dilemma could have made a difference in how my families engaged with one another. I’m grateful that I have the opportunity, as do many, to create history that leads to a better future.

As much as we might wish, we can’t control how people remember us after we die. But in that moment, even at her own peril, Shkurta demands that Ismail behave with integrity and honesty. When I think of Ismail’s description of the concept of besa, I remember Laynie Soloman’s writing on halakhah for SVARA, an LGBTQ-focused yeshiva; it “reflects the highest ideals of what we think the world should be.”

“I hope that your generation learns as much as possible,” Ismailaj-Valona told me, “about this beautiful tradition [besa].” Ultimately, Ismail’s Dilemma opens a window to the past to remind us of our impact on the creation of the future—and its radical, imaginative potential.

Mirushe “Mira” Zylali (she/her) is a writer and maker who roots herself in Mizrahi and Balkan Muslim feminisms, musical traditions, and arts. She received her Bachelor of Arts in Religion and Studio Art from Mount Holyoke College in May of 2021. Her love for the global mosaic of Jewish and Muslim peoples knows no bounds, informing her work and future hopes for a just world.

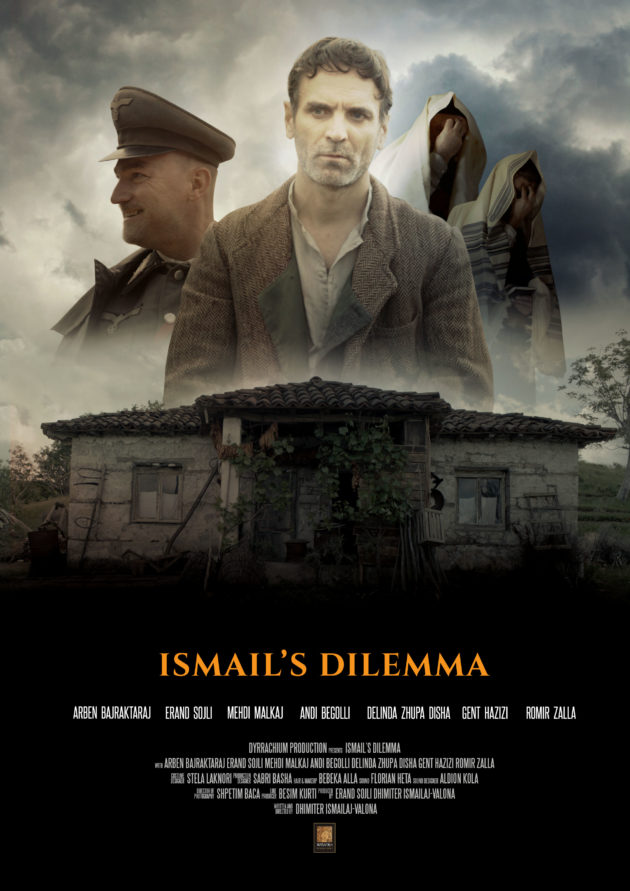

Film still from IMDB featuring Mehdi Malkaj and Andi Begolli in “Dilema e Ismailit” (2020).