What Magic Is Ours?

You can’t make a voodoo doll, I say, and begin pulling straight pins – one, two, four, arms, legs – out of the thick spool of white thread. The button eyes clatter to the table. It’s against our religion, I say, firm in protest.

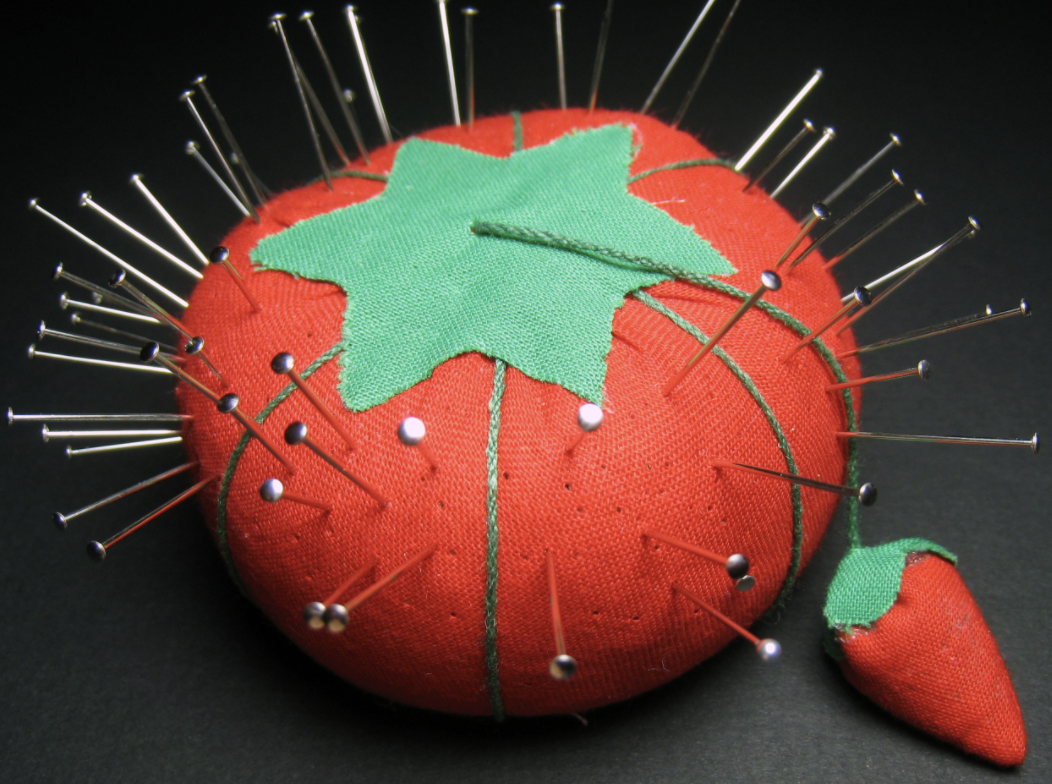

This is the third voodoo doll I’ve disassembled. All of them made from bits of my sewing kit. I don’t really sew. I just feel obligated to keep a well stocked sewing kit: this is one of the things I was brought up to do. My spools of thread are neatly aligned; tubes of needles securely fastened; my pincushion sprouts not even a dozen spikes. I’ve done so little home-keeping over the past year, though we have all kept ourselves at home.

My son wrinkles his face in consternation and pounds on the table. This doesn’t make sense to him. He gestures toward my kitchen. Toward my plants, my nettles and herbs, my tinctures and remedies, the jars of honeys and syrups shining like stained glass as the sun descends. It is nearly dinner time; I haven’t cooked anything, again. He would like to know: How is voodoo against our religion?

I say, God doesn’t want us to practice this type of witchcraft. I’m choosing my words carefully. It’s in the Torah. I think. I say, a voodoo doll is like an idol. It’s a representation of an actual person. Also, I say, it belongs to someone else. It’s someone else’s magic. Not ours. We can’t just use someone else’s magic.

What magic is ours, though, these days? Our cantillation and incantations seem to have lost the power they once held over me. Once upon a time, standing for the call to prayer on any given Saturday transported me. Once, as Rosh Hashanah rolled in, night overtaking day, the year and season changing all at once, I felt the opening of the gates, the potential for judgement and release, as keenly as the desperation I feel for breath after spending too long under water. The communal recitation of sin and repentance felt real, in those days: the cycle was one of renewal. Now, there is no renewal.

Now, there is no renewal: only motherhood, too little sleep, not enough nourishment, daily and weekly enactments of the person I am meant to be. I take the last pin out of the spool of thread, line them all up together, wind the skein again. You are a witch, my child says, the accusation one not made with hostility but with logic. If I am a witch, surely he can make a voodoo doll. Again he points out the essential oils, the talismans (pure superstition; I am easily taken in by anything that promises protection from the evil eye).

I am not even a very good witch, though. I do what I am supposed to do. I brush my hair, put on a skirt, paste a smile to my face, and go to services, where there is no more magic. I wait for it: I wait for the wave, for the moment that I will be pushed under, for the breathless panic of being thrown down-shore by the sudden rip of the tide. I hope that my grief will stop, or will overtake me: that I will be snatched from the barren place where I live now, where loss waltzes in periodically without so much as announcing its arrival, and shakes the edges of my tables, knocking everything out of alignment. One day, I hope, this disruptive force will take me one way or the other. In or out. No more in between.

The pins roll on the table. They won’t stay together.

You can’t make a voodoo doll, I repeat. It isn’t our magic to use.

I think of the magic that should be ours to use, instead. The faith we should have in our mezuzot and our medicine. A magic based on belief in the good.

Old Jewish ideas about magic rely on an understanding that there is something like a middle world, a place not part of the material world where we spend our daily lives, and not quite part of the spirit world. This is where one might – theoretically, if it were permitted – be able to conjure from. This is where angels and demons traverse, where protection from the evil eye might be acquired. This is where the last lines of El Malei Rachamim come from, the lines that promise our deceased beloved will be protected by the Master of Mercy forever, that hidden behind El Malei Rachamim’s wings, the beloved’s soul will be tied to the rope of life forever. Do we ever really lose them, then? Or do they just linger in the in-between place, waiting for us, or waiting for something else?

This is where I spend much of my time now, I think: in the in-between. Unable to bring myself to cook a decent meal, or to sew the holes in the children’s stuffed animals, or to venture back into the virus-soaked world, I try to remember the words to the psalms and fail. I have not sung the psalms since the pregnancy I lost – the particularly bad one. We’ve moved, now, many times, leaving behind community after community. Sometimes, I think, we don’t belong anywhere. Lately, I struggle to sing the morning prayers and simply sing, over and over, Baruch she’amar v’hayah ha’olam; baruch hu. Baruch omer v’oseh. Blessed is the one who spoke, and the world came into being. Blessed is the one who speaks, and who does. These words echo against all the echo words, and drown them out. These words become the only words.

The ambiguous grief of the past eighteen months has sparked a rehearsal of personal, collective, national loss, the same way that an anxious brain will begin, at the moment sleep is meant to descend, to replay every wretched thing it can recall. I am parched. The water has left me. Or I have left the water. In the in-between, I distrust the water. I distrust my own eyes; I barely see my living children, the ones in front of me, asking for a spell that will bring their mother back.

I stick the pins into the pincushion and my child scowls.

Bread, I say. And water. We don’t make dolls.

Ta’aniyot 5:9: This is the rite observed by the people as a whole who cannot endure more. In contrast, the rite observed by the pious of the earlier generations was as follows:4 A person would sit alone between the oven and the cooking range. Others would bring him dried bread and salt. He would dip it in water and drink a pitcher of water while worried, forlorn, and in tears, as one whose dead was lying before him.

“This is the rite observed by the people as whole who cannot endure more”. In contrast. The contrast refers to an explanation many verses earlier, a description of collective calamity and collective response by a people who cannot endure more. We tell ourselves, we cannot endure more. We can endure more. The collective informs the individual response. We turn to our collective response to understand our solitary grief: bread, and water.

In compensation for taking his pins, his buttons, his spool of thread, I bring out the bowl – twice a hand-me-down, gifted at my wedding, the bowl I use only for the most special of things, striped in blue and purple and brown and grey, the sea that flows through the world and through me and through my children wrapped in its colors – and the flour, and the yeast. The salt and the sugar. The eggs and the oil. And the water. I haven’t done this in months, but I know that pushing my hands into the dough is its own magic. The pins won’t stay together, but the dough will.

A round loaf, I say. You can measure.