Jennifer Anne Moses on Jewish Storytelling

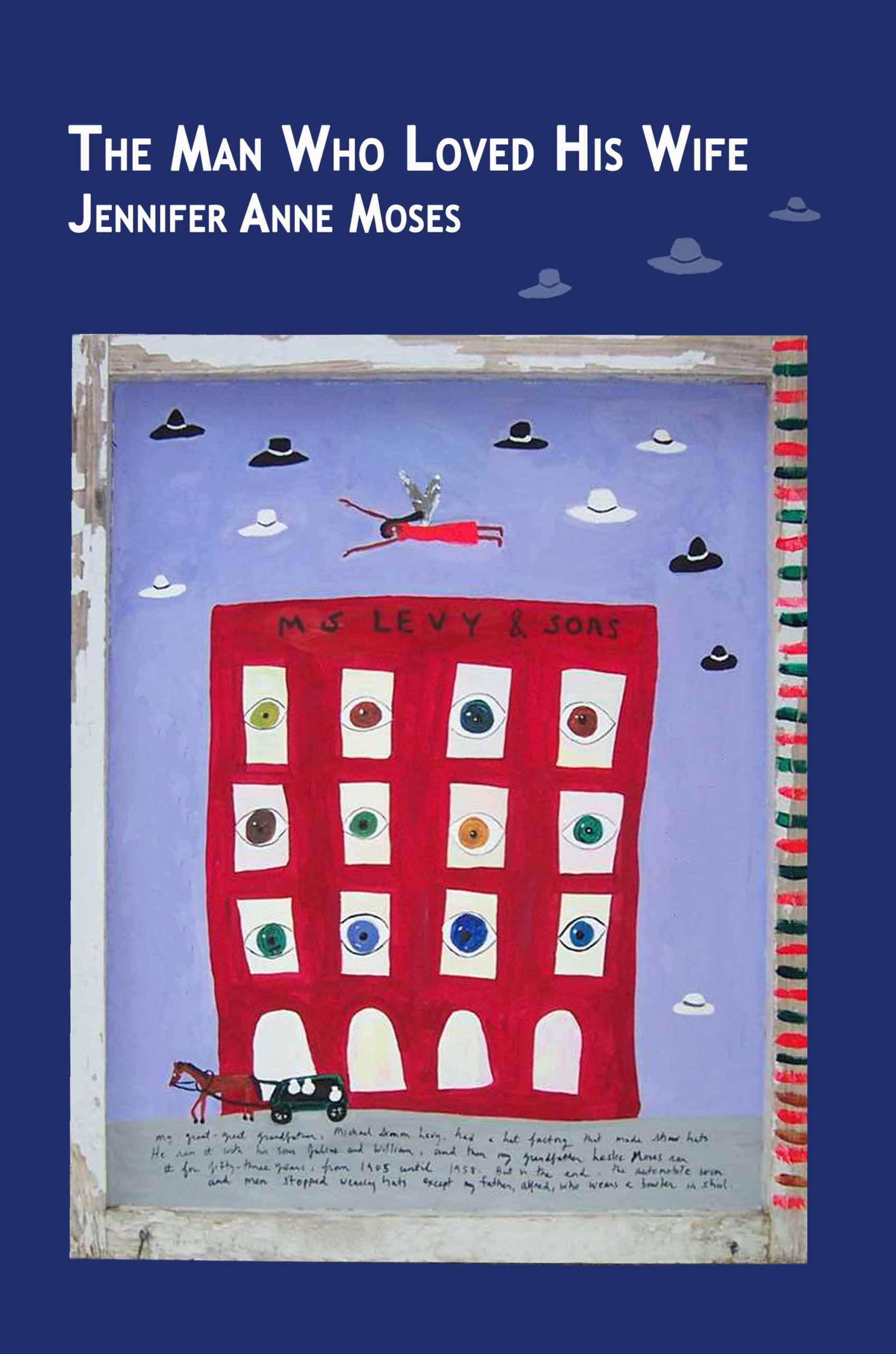

The stories in Jennifer Anne Moses’s new collection The Man Who Loved His Wife (Mayapple Press) are by turn funny, sly, poignant, and intelligent. And although they range widely in tone, setting and character, they share one common trait: they are all thoroughly and profoundly Jewish. Moses talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about her vibrant fictional world.

YZM: You’ve called these stories in the Yiddish tradition—what did you mean by that?

JAM: Let me start by saying that nothing gets me as deeply in the kishkes as Yiddish literature, which I didn’t know from until I took “Yid Lit” in college. From then on, I was off to the races: Shalom Aleichem, I.L. Peretz, I.J., I.B. and I.J. Singer, Chaim Grade, Esther Kreitman, Dir Nister, Bernard Malamud, Cynthia Ozick, Isaac Babel. I couldn’t get enough. The stuff just seeped into me, in my blood and bones, like some kind of (forgive the drama) divine elixir, an essential something that became a part of the way I translated the world.

So that’s part 1. Part 2 is that Yiddish literature, no matter what the language it’s originally written in, centers not only around Jews as a particular people living in a particular sliver of time with the specific difficulties attendant to their time and place, but treats the subject with a uniquely blend of humor, tragedy, pathos, grittiness, and a certain punchiness of language which has its own distinct, Yiddish-based rhythm. Everything is suspect; everything is holy; everything is fraught; everything matters; and through it all, the characters in Yiddish literature grapple endlessly with God, antisemitism, the history of Judaism, and the meaning of being a part of a tiny, distinct, and marvelously quarrelsome people. In this literature, t doesn’t matter if you’re a Reform Jew in Louisiana, a Hasid in Jerusalem, or an atheist socialist adult child a Holocaust survivor on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The ongoing tension of inhabiting a Jewish identity (no matter how assimilated, alienated, or agnostic) is what animates. As different as the stories in my collection are from one another, they all start with this one essential struggle: what is the meaning of being born a Jew?

YZM: The mother-daughter relationships you depict seem very fraught.

JAM: Funny, because by virtue of being the sole female, my daughter is hands-down my favorite child. I don’t mean this literally. My sons know perfectly well that I adore them too. Even so, you should only meet my Rose and you’d know exactly what I mean.

My own mother had three daughters and a son (I’m number two) and perhaps because from the get-go I physically resembled her to an uncanny degree, she had certain distinct ideas about who I was supposed to be. Though as a child I wanted nothing more than to fulfill them, I simply couldn’t. As for her mother—my grandmother, Jennie, after whom I was named—now there was a piece of work. Jennie was magnificent, beautiful, charming, cultured, well-read, and so controlling that the DSM should name a syndrome after her. I adored her. But she too had her ideas, largely about who her own daughters were supposed to be (and who they were supposed to marry, too.) So the sense of supposed to ran through the maternal line. A large part of my own adult life has been learning to distinguish my true self from my mother’s wishful version.

YZM: Equally fraught are relationships between sisters and even cousins—can you say more about this family discord?

JAM: I grew up in a tremendously competitive family, where to be anything other than “the best” within the wackadoodle but perfectly understood (by those inside it) family system was tantamount to moral failure. Suffice to say that by virtue of my nature, I was constitutionally incapable of so much as aligning myself with these markers of success—and as for achieving them: it wasn’t going to happen. So there was a lot of comparison between me and my siblings, as well as between the four of us and our many cousins, particularly our Boston cousins, who all seemed to glide through life on a magic carpet made of straight A’s, good looks, and being really good at tennis.

YZM: Another theme is Jews, especially affluent ones, feeling out of place in the mostly Gentile worlds in which they have chosen to live; can you speak to that?

JAM: I grew up in a slice of northern Virginia that was then so rural that there were more cows than there were Jews. Actually, there were more horses, too: a lot more. My father, who’d grown up in a very traditional Jewish family in a very Jewish slice of Baltimore had a vision of genteel country living, and so, along with the fields, woods, wildflowers and streams that were my backyard (front yard, too) I pretty much knew no Jews outside our own family. And we were yekkes. Not that I knew what a “yekke” was, and that’s because, by virtue of being a yekkes, I didn’t know what the word “yekke” meant. (It means German Jew.) The ideal seemed to be that we hang onto our superpower Jewish intellectual moxie while in other ways—tennis, skiing, summers in Martha’s Vineyard—inhabiting selves and lives more waspy than our all-wasp schoolmates. As children, all four of us attended a private day school modeled on the English public school, where we wore uniforms, danced around the Maypole, recited the Lord’s Prayer, and belted out the greatest hits of the Anglo-Saxon playbook, all the while wishing we too could have long blonde hair, small noses, and freckles.

YZM: Your stories are geographically diverse, set in Louisiana, the DC area, Israel, and London to name a few. Was it a conscious decision to create a kind of Diaspora in your fiction?

JAM: It was not a conscious decision, though what was a conscious decision was to choose stories in a wide range of intentions, including setting.

YZM: You’re a self-taught painter as well as a writer. Have you been painting as long as you’ve been writing? Or longer? What, if any, connection do you see between the two?

JAM: Longer. I picked up a paintbrush when I was a little girl, and by the time I was in the miserable pre- and early-teen years, I practically lived in the “art room” at school, where the teacher was so kind and gentle that to this day I thank God for putting him in my life. Mainly I did versions of pretty, Impressionistic landscapes. But somewhere along the line I decided that if I wanted to be smart like my smart cousins in Boston, I had to do well in school, and effectively put down my paintbrush in favor of books. It wasn’t a sacrifice: by then the urge to paint and draw had left me. Two decades later, I was living in Baton Rouge with my husband and (then) three small children, and volunteering once a week among almost entirely Black, full-Gospel Christians at a home devoted to the care of AIDS patients. Now and then patients and staff would gather in the home’s lounge to sing gospel songs, and though I longed to join in, my singing voice is rather non-fabulous.

Some of the staff asked me about my non-singing, and when I told them that I couldn’t carry a tune, they offered to pray over me, asking Jesus to grant me a singing voice. This went on for some time until one day I was compelled, as if by the force of an inner hurricane, to pick up a paint brush. I still can’t sing but to this day my paintings come out as painted versions of Gospel music–if Gospel were Torah- rather than Jesus-centered. Unlike my writing, the painting is both more innocent and almost entirely unlayered by education, and I think that’s because it bypasses my brain entirely on its way out my fingers and onto the paintbrush. As far as the connection between the two, and at the risk of sounding either woo-woo or plain old egomaniacal: when my work in either form is good–when it hits the mark—it’s because I am working as a vessel of what I understand and experience as God. I do the gardening. But God plants the seed.