“Take What You Need, Leave What You Can”—A Conversation with Chana Widawski on the Hell’s Kitchen Free Store

In March, Chana Widawski led the charge to create the 24/7 Free Store in the boarded-up storefront of a vacant bar and restaurant in Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen. Widawski, a social worker, told Lilith editorial assistant Arielle Silver-Willner about launching the store and its role as a resource hub.

AS-W: How does a free store work—and how did you find the space for it?

CW: There’s an epidemic of vacant storefronts plaguing our entire city right now. The spot was collecting trash and sometimes loitering and illegal activity. We decided to turn it into a community asset—something that would actually be beneficial for the community.

It’s open 24 hours, seven days a week—and there were people skeptical about how that would work. Many have been blown away by how well-maintained it’s been. Part of that is because there has been such enthusiasm from the neighborhood.

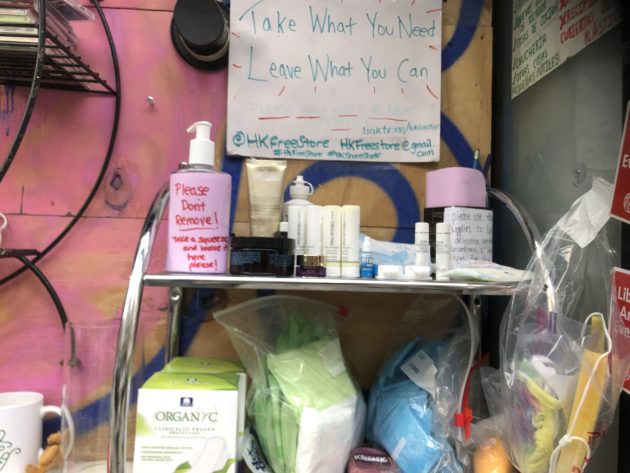

There was a book donated the other day called Poverty in Affluence, and that’s what we have in Hell’s Kitchen. People who are fresh out of being incarcerated, people who are staying in nearby shelters, and some who don’t have a bed in a shelter; they’re grateful for the toiletries that we have out there and other resources too. And then there are the people who are giving away Gucci boots and fancy nail polishes and beard-trimming kits. It’s a real mix.

It sounds like a great experiment in trust and mutual respect.

There was a post in our “buy nothing” group—“What if the homeless people took everything and ruined it?” But that would be great. We would fill it back up! It’s actually been the opposite, though. Every morning it’s in great shape. And that’s because we have so many people, including some of our friends and neighbors who are houseless, who have become stewards and curators.

We have a list of things that we can’t accommodate right now, because we’re in such a small space: food (a critical need for folks and there is so much wasted food); clothes or any textiles; and anything big, like large furniture. But we’re hopeful that a community fridge will soon appear nearby. People are stepping up to launch additional initiatives, which we see as a huge part of our success.

How did that happen?

It’s been kind of mind-bending for people—the idea of something that’s free, the idea of citizens taking charge of abandoned, vandalized space and turning it into public good, with purpose and possibility. There’s been a lot of enthusiasm through block associations, community groups, word of mouth, the media and even announcements from our governor. We would like that to come with an allocation of resources and public space to help more of these appear in neighborhoods throughout our cities. We feel like this is a replicable model and want to share a toolkit for other neighborhoods. The idea of circular economy and mutual aid is certainly not new.

We’ve connected a lot of people with resources—I’m a social worker, and this is some of the most social work-y social work I’ve ever done! People always want to connect—some neighbors have referred to the Free Store as the “new water cooler,” and when they need to meet up with someone or to connect for a moment, this is where they choose to do it. It’s not just about the exchange of goods, but it’s the exchange of human connection and resources and ideas and positive energy.

I think a big piece that doesn’t come out as much in all of the media stories is the powerful sense of community and purpose here.

The Free Store is having a powerful effect for individuals. What does this mean on a larger scale?

Landfill diversion. On any given night in this neighborhood–– and elsewhere––our residential trash and recycling overflow with perfectly good, usable items. A pattern in this neighborhood is transience, and people here for the short term stock their homes with high-end, wonderful products. When they leave, these things make it into our trash.

Part of this abundance comes from our consumerist society and our being programmed to just buy new and bigger and more and larger quantities and have it delivered and get it quickly—and it’s killing us.

We’ve put up a community bulletin board which is made out of cardboard boxes from the plethora of Amazon and other deliveries. We even have a little sign on the bottom pointing out what it’s made from and suggesting that people be more conscious of what they’re purchasing and reuse and share more, and buy less, and buy local.

How do you see the Free Store combating wasteful consumerism on a larger scale?

I would like to see 24/7 mutual aid neighborhood sharing hubs all over the city.

We look at projects like Material for the Arts and Big Reuse, and we need at least one of those on a large scale in each borough of New York City. From the corporate waste to what individuals are discarding at any given time, furniture and other large items could be reused, repurposed, and fixed if there were indoor spaces to be able to accommodate such things, both to prevent people from putting them on the curb to begin with, and for those of us who are out there rescuing things to have somewhere to be able to bring them. It’s painful to have to leave things behind on the streets and know they’re about to get crushed by a truck and then be on their way to a landfill, especially when others are in need of these very items.

The vacant storefronts that are sitting empty—we could be revitalizing those with reuse pop-ups that can be taken down quickly if a landlord finds a tenant. We could really use the help of our electeds and others to develop the infrastructure to cover whatever insurance or liability there might be and to help make it possible. We need the support and resources and hope that government agencies will give them to us, and also that the developers and real estate will do the right thing.

How does your own background factor into your work?

I am the child of a Holocaust survivor and that has ingrained in me a deep set of values, being able to find purpose in everything, plus a commitment to social justice. I feel like it’s the intergenerational transmission of trauma that makes me an environmentally and social justice-conscious activist. We often talk about trauma in a negative, clinical sense but it’s interesting to see some positive ways that it can manifest in us as well.

The Free Store’s rockstar team of women pay particular attention to contributions of menstrual products because they can often be difficult to access for folks. When we were setting up, I met a gentleman who explained that he was homeless and he was moved to tears by the Free Store. He stuck around for a good 45 minutes and helped and ended up emptying his own bag. Among the things he contributed was tampons—he had a bag full of tampons that he was sharing with others on the street. The tampons were loose (but they were wrapped!), and when I came back later, they were in a ziplock bag. I was so moved by that touch, that someone felt empowered to make the place as sanitary and productive and well-kept as possible. That’s the spirit of our volunteers, of chipping in and curating and stewarding.

Speaking of stewarding, how can we all take steps to live more sustainably?

Say “no” to single-use plastic and start thinking about this concept of “Zero Waste.” There’s a term that a friend of mine uses—“Beneficial Succession”—that everything has to have a beneficial byproduct. That goes for everything, from turning our food scraps into compost, to turning the cardboard box into our bulletin board, to passing something along so it can be reused.

Little things we can do in our everyday life can help us be in check with our values. Limiting what we buy in plastic containers and carrying our own vessels and instruments. I have been carrying the same metal spork with me for over 6 years now! For the most part, there is no need to ever take a single-use plastic utensil. I carry my own cup and something that can be a plate or bowl, too. I have a hard time eating takeout, because I don’t want the plastic takeout container.

But we also have to look at the big picture. Where is our money held? What are our banks funding? It’s about asking questions, always. What is the impact? What are the ramifications? It’s about recognizing that everything we do in our lives has a ripple effect. It’s the small stuff and the big stuff. How can we make sure that the way we live everyday is aligned with our values?